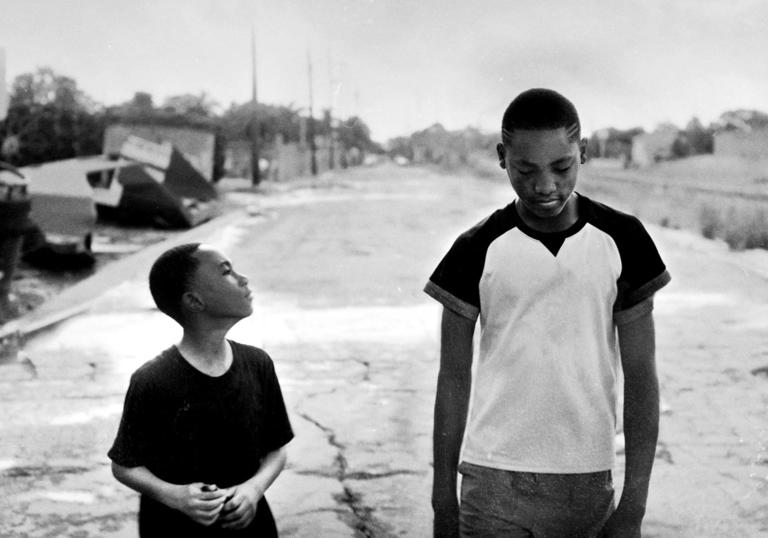

Ellen E Jones: Welcome to the Barbican ScreenTalks Archive podcast. Every episode we dig into the Barbican archive to find the best and most illuminating recordings from nearly 40 years of filmmaker Q&As. This time, we have an absolute must-listen for anyone with an interest in documentary filmmaking. It's director Roberto Minervini talking to the Doc Society's Head of Film, Shanida Scotland about his striking 2018 feature, 'What You Gonna Do When The World's On Fire'. Though born and raised in Italy, Minervini has been living in the American South with his wife and children for several years. It's in this adoptive home that he has filmed his third documentary film, telling four parallel stories of African-American living in the neighbouring states of Louisiana and Mississippi. They are young brothers Ronaldo and Titus, whose childhood of carefree play has already been encroached upon by the concerns of the adult world. There's also chief Kevin and the flaming arrows tribe who keep old traditions alive as they create costumes for Mardi Gras. And we meet the new Black Panther party led by Christal Mohammed, protesting police brutality and racist hate crime. As Minervini explains, all of these connections came about through his friendship with one remarkable woman, Judy, the owner of the Ooh Poo Pah Doo bar in New Orleans. That bar was the director's hangout spot as the idea for the film took shape. Minervini talks about why he was drawn to these people as subjects and collaborators, and how they in turn influenced his pivotal decision to shoot on film and in black and white. He also describes his convivial family friendly shooting style, which would come as no surprise to anyone who has seen and appreciated the intimacy in this documentary. It led to lasting friendships, not only between the crew and the people in the film, but also among their children. Minervini hasn't necessarily kept in touch with the right-wing militia that he mentions at one point in this discussion however, that sit down was actually for his previous documentary, 'The Other Side'. Documentary makers talk a lot about the need to build trust, and as you'll hear, that really is the beginning and the end of Minervini's process. He's very clear that in the context of the documentary about Black Americans, made by a white European, trust could only arise if he was absolutely upfront about his own prejudices going in. And at the centre of all this, is that evocative title. Minervini explains its origins as well as teasing out the different layers of the question, who is asking it? And just as important, who is answering?

I'm Ellen E Jones, and this is Barbican ScreenTalks with Roberto Minervini.

Shanida Scotland: Thank you for such an incredible striking film with so many stark and harsh realities going on, and you found an incredible group of contributors to your film, and I wanted to ask, really, how you found them, and how you got started with the film?

Roberto Minervini: So there's a couple of starting points. One being 2016, the year where there were a series of murders by the hand of the police, or young black men at the hand of the police that went unpunished. Some of them made international news, back to back, July 5th and 6th, murders of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, the guy with the little girl at the back of the car, but then 9 days after the death of Philando Castile, a young African-American killed three policemen in Dallas and said it was time to take action, and retaliate. And there was something unprecedented for our generations and during the electoral campaign of presidential campaign of Donal Trump talking about the dangers of downtown, you know, mainly black downtowns, like Chicago, living in the South I remember vividly the emergence of the fear of black people again, one more time. That was one of the starting points that motivated me to go to the neighbouring state of Louisiana first and then Mississippi, looking for people to talk about this experience, of being together, and talking, and meeting halfway, me being white or European descent and them being black or African descent.

That's how it started but the first person I met was Judy, I met her at her bar, because I was looking for musicians since music, especially black and folk music from the south, jazz, always carry the oral history of Africans, Americans and African-Americans. So Judy is the daughter of Jessie Hill, this prominent musician and I ended up hanging out at the bar at Ooh Poo Pah Doo on Wednesdays when she performed and we hung out, literally, for about a year, before we decided that perhaps we could, there was a film there to be made. That was the starting point, the kids, the brothers, the uncle, lived on the top floor of the bar, and Judy is queen of the Mardi Gras tradition so I met all the Indians, especially the Flaming Arrows tribe with Chief Kevin, so that was the starting point, it was political and also, anthropological sounds too big, it was just me really hanging out and being open and honest with people.

SS: There's something in that hanging out as you call it, because it's clear you developed an incredible amount of trust with your contributors, that takes a lot of work, and it takes a lot of work for them to meet you, and you to meet them too. how did you go about that, was it just a matter of, you know, as you say, just hanging out at the bar, but also with the young boys and their mother, tell me all about that.

RM: First, there is a little bit of personal background here that I feel is relevant, but maybe not . Through life experiences, I got to believe that in order to establish some sort of intimacy, the pre-requisite is openness and honesty, it sounds cliché but it wasn't cliché to me, I don't think I live a life in honesty all the time, and I'm being a liar myself, and I'm being a manipulator myself, and at some point I had to start a catharsis and be on the way to becoming a better man, a better father. That is important to me, very important. I'm very strict in that, and how I go about life. When I went to Louisiana, Mississippi, one of the first things I did was talk about my prejudices, not, my being liberal and open and being, I don't know, some sort of champion of equality, it's the other way around. I had to start from a place of vulnerability. I talked to Judy first, then to everybody else, what it meant for me to be there, it meant that I was still possessed, I was not necessarily a victim, but the prejudices or the stereotypes of going to a gas station at night, in a black neighbourhood, and seeing a couple of younger men, profiling them, perhaps subconsciously, you know, if there's something bulky in their pockets, being scared and fighting within myself to say this is not how it's supposed to be. Having said that, my emotional response there, and emotional response come from something else, so here's where I'm at, I'm willing to open up, I'm willing to do my work, but this is where I'm at today, I'm not immune to racism, I am white European, I feed off mainstream media information, at the same time, I have some power, I can put the spotlight wherever I want, so despite my own flaws I got a lot of work to do, this could be starting point. And that was a starting point for building trust, because some of them could at least trust that from this point of openness, and perhaps we could build something, you know, which we call intimacy.

SS: How long did you shoot with the contributors?

RM: So I always shoot during the summer, the whole summer. Being a father with kids in elementary school, I need to use the summer, because they come with me, the family relocates with me and my kids are all involved, not in the production of the film but in life, like you know, Ronaldo and Titus were having sleepovers with my kids, and so on and so forth. So summer, that's kind of when I conclude, I complete the shoot, so that was the summer of 2017, I started shooting chunk of time in September 2016, let's say maybe five months of shooting, but I started hanging out with them in 2016. About five months.

SS: You mentioned you're a white European man, I understand now that you do live in the South, in the American South, I know your other film also set in, based around communities and the American South, why, what's the fascination, is it because you've been there, is it because, how long have you been there? The American South has a long sort of fictional gothic history as well, but you're doing something obviously quite different, and this is a documentary film, so tell me how that kind of all works for you.

RM: So I lived in the US, been living there for two decades, and 13 years in Houston, Texas. My wife grew up in Houston, but I was living in New York for the first seven years and I was deeply dissatisfied with the way the intellectual left élite operates, the modus operandi, and the philosophy, and there's where all this thinking about, you know, inclusion, exclusion, which is a lot of, you know, the classy sugary issues, all that process of awareness started in New York City. The city of self-proclaimed, you know, liberal city, which is in fact, statistics say that it's the third most aggregated city in America, where everybody, including myself, thought that we were very content with the minority representation and inclusion, and considered that a point of arrival, not a point of departure to reach equality. I mean, it's an afterthought, liberal America. I remember talking to people and exploring, talking about minority representation, I marry into, you know, my kids are mixed race, so it's a hot topic in my family as well. I remember asking ourselves that we would never put our kids in an all-white classroom. But, would we put our kids in an all Black classroom? And I've yet to find someone who is willing to do that. In New York City I remember there was a hot topic, and long story short, I decided to get out of there and relocate to the South. Why document the people on the fringe, on the fringe of society... Several reasons, one is my background is blue collar, i come from a small town in Italy where there's no, you know, none of my family, me and my brother were the only ones who got a college education, but none of our parents have any education, that was not our path. When you're outside of the spotlight, there is some sort of very primordial sense of resilience and courage and that grows into people who were out of the spotlight, and that I find very, I feel comfortable with their sense of their resilience that comes from people with very little and lived at the fringes of society. And the honesty and transparency. So that's how and why I'm drawn to them, because I can have open honest conversations with right-wing militia people, and sit down at the same table, and I don't find that in the upper echelons of society, I don't find that openness. That is the reason why I'm drawn to this community in the South, I would say.

SS: And then obviously, in the film it's shot in black and white, and you shoot these long takes that slowly build, but also indicate flexibility in your shooting style as well. And the fact, that, as I said, it's in black and white, they're quite deliberate choices, I wanted you to sort of invite us into that decision-making, a little bit, please, and talk through.

RM: That's something, the black and white, using black and white is something that I decided even before knowing what kind of film I was going to make. I was talking to Judy first about it, we shot some test scenes here and there, the Indians one time, we were talking about what it meant to shoot this film in black and white. We all agreed on something, on the historical aspect of it, of tying this film directly with, or creating a continuum with all the iconography of the Civil Rights movement, where all the iconography is black and white, so we all agreed on our attempt to iconise them, we were all on board with that. Then, as a filmmaker, there's another aspect, there is the fact that colour creates a hierarchy of beauty and ugliness among them, and among their spaces, and dresses, the example could be, the Panthers with the black uniform and empty spaces, or highway underpasses, and the Indians with beautiful, there's nothing black and white about their dresses. And I didn't want the hierarchy of beauty, because that has an effect on how we engage with them. The Panthers would've ended up, and they're already struggling to be heard, and I would've put them at the bottom of this ladder, of beauty. So I didn't want that, I think black and white grants them some sort of equanimity, and we can navigate through stories without engaging in a concept of beauty that, by the way, beauty of colour is also white European as a concept. So there's a lot there, there's my own thinking as a filmmaker, but definitely we all agreed on the fact that we needed to tie this film into a particular historical moment that was really important to us, especially to all of them.

SS: And it's absolutely what you say, isn't it, that in shooting in black and white, we sort of elevate the voices or elevating what they're saying. And actually, there's no music, but the music is sort of naturally created in the film as well, so obviously all of those choices. And your director of photography, he was involved in the conversation with Judy as well, and...

RM: Yeah, I work with the same people, I've always worked with the same people, the shooting crew is four of us, me, Diego (DOP), we both share camera operator duties, because we don't cut our long takes, we just pass our camera on to each other's shoulders, we can hold it for 15-20 minutes, then there are two more people with us, and then back office, there's four more. In total 10, but four is that core. The reason why I like it that way, meaning I can never be a one man show, a documentarian by myself, is because each of them have their own relationship with them, with the characters, with people involved in the film, they're with their own attachments, and emotional implications, and friendships and loves and all that. So of course they're involved in all the creative process, and they give input to me, but it goes beyond that, that is a sub-product of the fact that they all, including Diego, have their own relationship with the people. For example, my wife and Judy have a friendship that is their own, it continues now, and me and Ronaldo, the older boy, we're very close, I'm also close to Miss Ashley, the mother, obviously, because she's involved with this special friendship and bond that we have. So people have their own, you know, Alexis, mind you, is another one, a strong friendship with Chief Kevin, they see each other. The foundation of the way that I shoot is very convivial, it's very family-oriented, we relocate there you know, there's partners and kids, everybody participate. That has an effect on how we co-exist, and that has an effect on the input we bring, and what we bring to the table when we shoot.

SS: But then, obviously it's this community of filmmaking, community-style filmmaking in a sense, with your contributors. But you also have to edit, you're also dealing with harsh realities, especially with the boys who often felt, you know, watching them sort of evaluate their own horizons and what their possibilities could be, and Judy has so much going on, and the new Black Panther party as well, and you have to make choices as to what's in your film, what is your film. So I wondered how you came down to those four threads, and did you lose any characters? I think you said you shot over a summer, so that's obviously quite a lot of footage, so what was that like, was that quite singular for you?

RM: Yeah there's a lot to say about that, so I'll try to be, being succinct is not one of my strengths, but I'll try. Because of the open nature of the way that I shoot there is some, the genesis of the project is almost, you know, it's almost auto-genetic, I'm filming with people I'm hanging out with, and I film stories, I have an idea from the beginning, that this was going to be an ensemble stories, perhaps never converging. I did have a feeling about that, but then I started filming tens of stories, and some of them fizzled because the intimacy wasn't there anymore, maybe from my side or their side, you know, or maybe we just didn't want to be in it for the long run, because you know, this relationship is a long-lasting one. That is also something, because in the beginning we know that we were going to do something that transcends cinema here, and we're going to engage very deeply, so some of the stories just didn't go through, and I wasn't trusted, I didn't gain their trust, I didn't deserve trust and vice-verse. In the end, since I don't review footage, because if I start reviewing footage then I start having a pre-conceived idea of what the film could be, inevitably. So I don't review footage, ever, until later on in the editing process, so I talk about it, I keep the memory of what we're doing in the moment, I keep it alive, and I talk to Judy and these people and I tell them that I'm seeing stories, almost algorithmically, wow, it seems to be going to point B from point A, and there is a possibility of B1, B2, B3, and then we all contribute. So we already all have a sense of how this film could take shape.

Then we have 150 hours of footage, and I send them to Belgium, to an editor who barely speaks English, and who has to review the film, and to me that's the magic. For me, that works really well because she has to rely heavily on emotions and this is how we film as well, because I'm really the only one with the crew members who speaks, I mean who understands English fairly well, I would say almost everything when I shoot, but the others sometimes they have to gage faces and emotions and go with their own, well, feel, and sense of attachment. That's how we start editing, Maria Len, by herself, trusting her own feelings and then when we get together, all those prejudices come back into the discussion, what you feel, what is this something that has to do with your being European and back and forth. So it's a complicated process, with all those ingredients, right, our cultural background and political beliefs, ideology, language barrier, all of them play a role in finally making a selection, and it's very very draining this process, we always end up crying and laughing, it's like the movies - we laugh, we cry, we hit each other, we separate, we break up, then we get together again, I mean, Maria Len and I have a special bond because it's extremely melodramatic. The editing process is so melodramatic, because it's so intense.

SS: You talk about this editing process where it's very emotional, you're relying on emotions really, you're dealing with people who have given you so much of themselves and you're trying to be really vulnerable, it makes me think that actually it's maybe a really simple thing, but the title, it's a really striking title - and there's a question here about who is it really being directed at, so I wondered if you could talk about how you came to that.

RM: This is a big question for me, the title. There is a gospel that carries the title, performed Lead Belly and Anne Graham, this very obscure singer, but, you know, the answer, 'What You Gonna Do When The World's On Fire', the answer is always is always the same, 'I'm going to run to my lord'. and running to lord has two meanings, right, the lord as in, God, and the other one being the slave owner. And that also answers the question to me, right, who am I? I mean if there's fire, are they running to me, am I, do I represent power? Salvation, in a way? It's a big question, I think. It's directed, I think - look, Judy answered the question for herself, she had a very clear answer, if you're white, you run away for rescue, you'll be rescued. If you're black, either you burn in flames or you'll rescue yourself. That's how it is. It was kind of a matter of fact answer based on experience. Experiential historical, and me, so that's why the question or perhaps the question to me as a white European guy, I don't know, it's totally true that I always feel safe, I never feel unsafe.

You know in life, everything comes fairly easy being born white European, but also the fact that the burden of, I need the awareness over the fact that I perversely represent safety, I'm the danger to some classes and races, but I'm also safety, like a slave owner, which is absolutely, it sent me to a trip, like a catharsis, to say the least, a tremendous personal crisis because it's a fact, it's a reality, I don't know, I can only answer the question for myself, you know, the world is not on fire for me, and then, what is my responsibility around that, because if it's not on fire for me, am I going to just sit comfortably like I've been doing for a long, long time, or what?

SS: I think that's exactly it. We've just watched people who have sort of really left to look after themselves, in the most emotional heart-breaking ways, they form their own communities, they're helping each other succeed, get through life, and the toll is really kind of, it's who is asking that question, who is it directed at? They've almost in a way done enough, they're trying to do enough, they do enough every single day.

RM: Yeah absolutely, I'm just going to throw in an anecdote which is not really an anecdote, it says a lot about me, and this process. You know, the Black Panthers, right that wasn't a walk in the park to gain their trust, I formally contacted them through email, they called me, and they, background check, and their several meetings, two months of meeting where I was also challenged ideologically. And still, understanding that there is a line, a demarcation line, you know, them as nationalists, and me as a white guy, despite all that, perhaps there was a way here of communicating and doing something together. But then, Krystal Mohammed told me, okay, and I was like, my grandpa's name is Soviet, Marxism is a piece of cake, I understand everything, I did my homework, I read the book 'Black Power' and all that - 'Yeah ok, and now welcome to the dark side'. I said, 'Hold on. what dark side?'. And that's about the world on fire, what you gonna do? I thought what am I going to do, I'm a filmmaker. and then I asked the crew members ,they all thought, 'I don't know if I want to go to the dark side'.

And people were saying 'Yeah, you know I got work to do, what if I end up in jail, like yeah, and me, I have kids!'. I said 'No' to the Panthers, I said sorry I can't do it. But I didn't tell them the truth, I just told them it wasn't working for the film. So I put my filmmaker hat, and I ran away from the fire. Immediately. And it took me a good month to realise, and that's why I go back to the emotional reaction, I said okay, my emotional reaction of tremendous fear, says something about where I'm at, culturally and ideologically and all that, and I said, I must go through it. If I don't even share a little bit of the dark side, that's what I did, a little bit of it, then I'm utterly unqualified to even start considering the possibility of making a film. So I did it. Did I want to do it? No! I dreaded every single moment that I was with the Panthers, every time they took the R15 to perhaps protect other people, I said, 'I don't want to be here'. You know, I know where I'm from, I know what safety looks like, safety is my condition, I've been given that, why do I need to... So I kept myself in check a lot, and today, I have a relationship, I have a little bit of dark side in my life, and it's a very strange thing to me to have experienced this. That is not my world, it was not supposed to be, and to still be white and powerful. There's this schizophrenia there, short-circuit that I haven't figured out how to fix yet.

SS: Is it on release in the States? What has the reaction been?

RM: It was released obviously, limited release, in main cities. Every time we had the premiere at the Lincoln Centre, we had it twice, at the New York Film Festival and the theatrical release, the Black Panthers are contingent, the Black Panthers always came, always shared the stage. And they did in London by the way, at Frames of Representation, last April, so you could see the difference. London, it was a rousing experience, I cried because I was intimidated, in a way, by the experience, it was so empowering, a lot of Black activists and I felt scared and inadequate and all that. In America, with Americans, to have five Panthers here speaking their truths, people don't want to mess with that, people really, nobody really, the reaction is very subdued.

So in America there is no steal, there's no room for that kind of open debate and confrontation. In London, someone even told the Panthers, 'I wanna know if you are anti-semitic or not', we need to talk about this, we need to open up. In America, they'd rather avoid it. Which is, again, it's part of our idea of keeping, you know, holding on to supremacy, right? You want to engage in a debate because that could open avenues there that you don't want to get into, because if you want to engage with them, you want to talk really about what supremacy means, and they talk to audiences, like, 'tell me about your democracy', let's talk about democracy in your country, bring it on. So yes, it's being released with a very subdued reaction. At the moment I feel very safe, like, bring it on, you want to say something to me? I got the Panthers. The same who'd scare me. [Laughter]. That is just a joke, although emotionally it was true. I feel pretty safe at the moment with the Black Panthers on my side.

SS: I just wanted to ask you about the Mardi Gras Indians, I know you wanted to talk about them a little bit earlier, what they're doing is very much trying to keep a hold of much of their rituals and memory-making for the community. It's quite a hopeful thread throughout the film, tell me a little bit more about that.

R;: Yeah, so for those who don't know, the tradition of the Mardi Gras Indians started after slavery was abolished, and there's been a bond and a mutual understanding of their conditions, between American-Indians and African-Americans, newly-freed black Americans without papers, undocumented. During fire they kind of helped each other, and it's been a mix of racial and, um, how do you say that? So a lot of black people carry Indian blood like Judy, she carries Cherokee blood, and Miss Dorothy, her mum. So there's this celebration of this alliance, allegiance, and paying homage to a tradition that is still alive today. Now, black people were not allowed to celebrate Mardi Gras during the day, so they did it at night, there is a special day for the Mardi Gras Indians which is St Joseph, Sunday night, and keeping memory alive, all those things are absolutely true. But there is something else that is very tangible for me, that I had the fortune and privilege to be, to spend a lot of time with the Indians, it's the reclaiming the territory, a land, a soil. That no matter how much they pave it, and they cover like their kind of history, it's still theirs.

And they're reclaiming that territory back at least once a year, with those chantings, with those walks in the neighbourhoods and then it was a serious matter, I mean three decades ago, if you stepped in front of an Indian chief, you get killed. I made that mistake while filming, you get hit, you get hurt, you don't get killed anymore, but, you know, I got hit with a bullhorn and it was a Chief that told me to get the hell out of my way, because the idea of reclaiming a territory is still very important. And that's why the film, without getting into details, because first of all, my time was not to deliver information, my time was to observe, and be an intermediary maybe, a facilitator. That's why some people ask me if there's hope, I don't know, all I can say is that the film opens and closes something that represents legacy, tradition, something that stays alive, and also, you know, reclaiming a soil, a territory that is no matter how much they take away from them, will always be theirs. And as long as that memory stays alive, there's no death, in a way, there's no disappearance of a condition, or a race. All of that was very important - if there's any hope, it's just that. That resilience that I witnessed everyday, that won't die.

SS: Please join me in thanking Roberto Minervini for joining us tonight.

RM: Thank you.

EEJ: Thank you for listening to this Barbican ScreenTalk with documentary filmmaker Roberto Minervini. In every episode we bring you a different example of a filmmaker talking direct to their audience about their craft and inspirations. To support the podcast, you can rate and subscribe via Apple Podcasts, Acast or your usual podcast providers. Or visit Barbican.org.uk. And if you have any thoughts you'd like to share about this podcast, or film at the Barbican in general, you can find us on social media @barbicancentre.

Barbican ScreenTalks Archive is presented by me, Ellen E Jones, and produced by Jane Long from Loftus Media. We'll be back next time to talk about a tale of forbidden love between two Georgian dancers, the soul-stirring 2019 film, And Then We Danced. Until then, be well and goodbye.