The earth goddess Gaia, like all mythical figures, was a means by which classical society could reason the – at that point – unreasonable. Without the available means to see the planet as an object, to gauge its matter, circumnavigate its outer edge and gain some physical understanding of ‘life’, artistic depictions of Gaia, in sculpture and painting – with her nurturing body, an ancestral mother of all life – provided a ‘thing’, an object for attention and projection.

What does climate change look like? What does it feel like? Sound like?

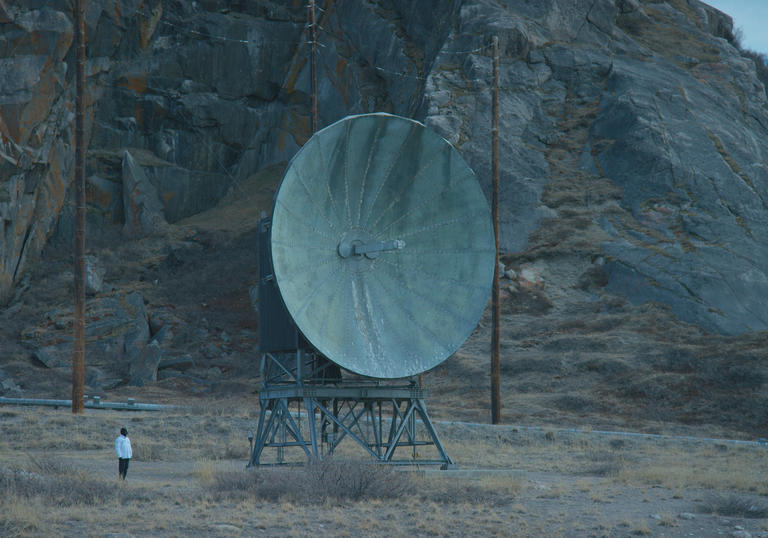

However, it would be a mistake to surmise that we are presently in any better position. While science and technology has allowed a greater understanding of how the world operates, how life proceeds, that knowledge has only further alienated the individual from the big histories of the earth. What, for example, does climate change look like? What does it feel like? Sound like? Very occasionally we might be able to see the results of climate change with our own eyes, but we cannot see the thing itself. We can measure declining biodiversity, but for the most part, we won’t bear witness to it physically. We can, and should, acknowledge the macro effect of mining on the earth’s geology, but we must do so through data and description, not image and experience. These knowable, unknowable ‘things’ have come to be termed ‘hyperobjects’: things so great that they operate beyond comprehension. The biggest of these big histories, the most hyper of these hyperobjects, is the Anthropocene, the position that humanity’s effect on the planet is so severe that we must count it as a new geological age.

If classical descriptions and depictions of the goddess Gaia can be retrospectively considered a hyperobject made incarnate, then John Akomfrah’s new six-screen moving image installation, which fills the Barbican’s Curve gallery, can be considered in a similar tradition. As the follow-up to Vertigo Sea – Akomfrah’s 2015 poetic ode to the oceans and humanity’s fraught relationship with them, first shown at the 56th Venice Biennale – the artist’s new work seeks to visualise and make audible the Anthropocene.

The artist brings into sublime focus our standing on this planet

Purple does not follow any one linear narrative, nor confine itself to a human centric perspective. Moving beyond the intra-special struggles of Akomfrah’s earlier work, images and sounds from vanishing ecologies across the globe intermingle in this symphonic, panoramic, artistic gesture to create a portrait of humankind and its ecological kin. The stories emanating from the hinterlands of Alaska, the ice shelves of Greenland, the coral reefs of Tahiti and the volcanic rocks of the Marquesas Islands weave together symphonically. It is a filmic structure that recalls the complex interrelations of the world’s natural landscape. In turn, standing before these vast projections – in a work that, given its size, is never wholly viewable, spatially or temporally, at any one time – the artist brings into sublime focus our standing on this planet and proves a searing reminder of the outsized scale of humanity’s destruction wrought here.