Carole Woddis: How did Unexploded Ordnances come about?

Split Britches: It developed from an artists’ residency on Governor’s Island in New York Harbour, which used to be a military base, a fort during the Civil War, and an active service base during the Cold War. Now it’s a national park. A woman across the way from us was doing beautiful maps, one of which was of the harbour. On the bottom were numbers for unexploded ordnances, or cannon balls, from the time of the Civil War. When the guy who was giving us a tour around the park said: ‘you can’t stick anything in the ground here. It might hit a cannon ball and blow us all up,’ it turned into a light bulb moment. We thought ‘this is a perfect metaphor for unexplored potential.’ We had been doing work with elders at this point because of Peggy’s stroke. So we were in the mode of working with subjects to do with elders.

CW: Why elders specifically?

SB: Because we’re getting older.

CW: Yes, you’ve always done work using your own lives and experiences.

SB: We’ve used performance to help us get through. It’s been the material for our work.

CW: You did a residency at the Barbican after your last show, Ruff. What did you discover?

SB: We looked at the idea of digging and desire, at things people had always wanted to do but maybe never had a chance to do. That was a real starting point alongside the idea of Dr Strangelove.

CW: Where did that come from?

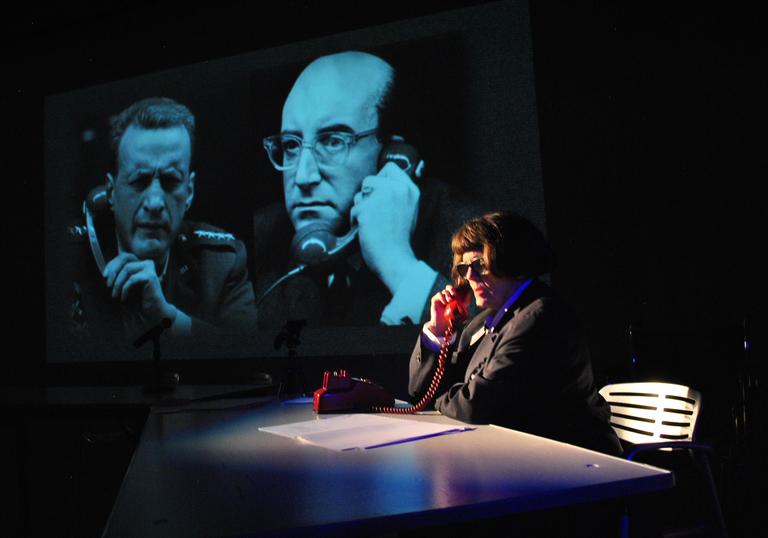

SB: We just got obsessed with it. It’s a really scary, funny, ironic film. Peggy had always wanted to play George C Scott and Lois is a perfect President. What’s also interesting is that the film deals with the urgency of time, of time running out. It’s uncanny. When that film was made, we were in a nuclear moment and it was relevant for that reason. Time went by, we thought things were under control. Now the threat is back and we have already situated ourselves in that material … as artists, you can feel what’s coming.

We also wanted to explore what’s hiding underground, what’s been covered up that might get uncovered as the top soil gets blown away by climate change. What are the military aspects of our past that might haunt us – happening now in the USA – unexpressed tensions to do with the Civil War such as white supremacy, slavery and racism.

Having done these residencies, one of the main interests was to find alternative ways to engage the public, of putting performance and Split Britches’s popular entertainment right up against giving people the ability and the platform to have important conversations. Because the other thing that is really important and which has grown since the US election is the need to talk to each other. We’re not going to survive if we don’t find ways of having these conversations, disagreeing with each other even if just across a table.

CW: What else have you discovered in your residencies with elders?

SB: That we are an untapped resource. There are still things we can offer in terms of conflict resolution, creative ideas and lived experience. The unexploded ordnance is the idea that those resources still live within us. If you identify a desire you once had, you can use it to think creatively about how to solve a real worry. That might sound whimsical or unobtainable but you can’t change something unless you can imagine it.

CW: Do you think the show has the potential to change people?

SB: We hope so. Every night will be different. We’ve always wanted to change perceptions. At this moment, we want people to look differently at the potential within older people. And also to look differently at their own ageing. Because we’re all ageing. Giving elders visibility in theatre and making people feel better about themselves is what drives this piece.

CW: Working in this new interactive way with a Council of Elders, how does it fit with your usual performance style?

SB: We perform around the elders. Peggy plays the bombastic, Trump-ish, General [played by George C Scott in the film], Lois the Peter Sellers, mild-mannered President. We play those archetypes against each other. Part of the Split Britches way of working has always been to locate popular culture references that we can inhabit and appropriate. There’s that layer but there’s also one about our real relationship, which is always there. We try to equate the personal with the political. We have the critical moment where the bomb might drop any minute and that’s true in the show.

CW: Do you still have hope? I suppose so because you’re looking at unexplored resources.

SB: It’s very hopeful. A lot of the hope comes from older people. One of the things we’ve found in conversations leading up to the residencies was that if people were ok – fed and sheltered – they reach a point where they’re not afraid. They’re willing to take the risk, to try things they haven’t tried before, to live in the present in a way that those of us before that point don’t so much. And don’t forget elders have lived most of their lives without computers. Social media gives people little hope because there’s so much negativity, ranting and raving.

But there is hope, in being able to talk to each other, to be able to gather in the same room and have conversations and create this little community. That’s what live performance in theatre can do and that’s how it can change us. You just have to show up in the room.