Some questions for Boom for Real: what tools, what language, what new ways of being together do we have now that we didn’t have then with which to read the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat? How has the work changed (which is also to ask, how have we changed)? And how does the work read us now? Fortuitously a new commission, Purple, is currently on show in the Curve by the ferociously brilliant artist John Akomfrah, who claims Basquiat as an influence. Housing Akomfrah and Basquiat at the same institution changes the conversation.

This is a crucial time to look at Basquiat again given major global cultural shifts including the rise of more African-American, Caribbean, Latin American and other diaspora artists and writers; the rise of “First World” discourses on diaspora; the rise of intersectional black theories (such as black feminist theory, black queer theory, etc) and new histories of black expressive cultures; the rise of critical theory; the rise of alternative histories of conceptualism; the rise and increasing visibility of black immigrants in North America and Europe; the development of institutional support for the arts outside of North America and Europe (through museums, festivals, prizes, biennials, etc); and the endurance and renewal of anti-colonial and black radical movements that continue to fight institutional racism in all spheres. Do we now, finally, have more tools with which to see him?

It is no surprise then that in the last few years there have been a considerable number of major international exhibits of Basquiat’s work. How can a Caribbean city like London change the way we look at such a major Caribbean-American artist? In 2014, the city of Paris named a public square in its 13th arrondissement after Basquiat. In the public mourning and protests of the deaths of Sandra Bland, Rekia Boyd, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Walter Scott, Philando Castile, Andrew Loku, Mark Duggan and countless others (our terrible litany) by police, Basquiat’s iconic paintings Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981) and The Death of Michael Stewart (1983) continue to be posted again and again on social media.

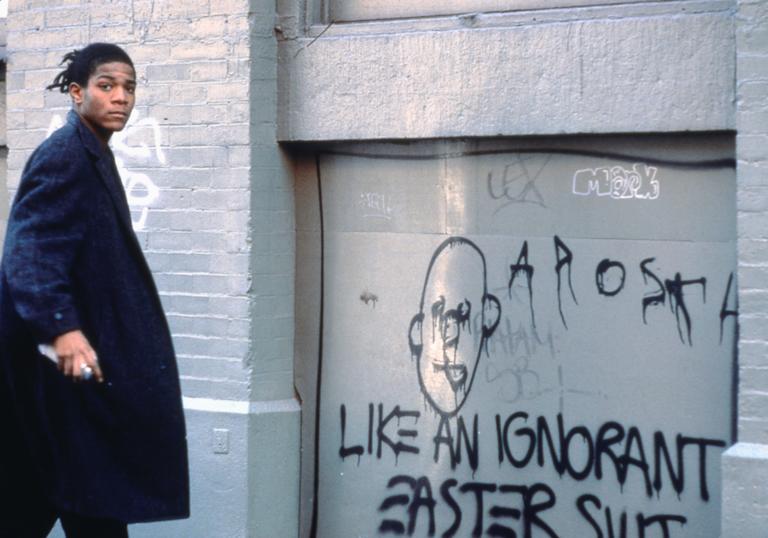

For me, the work is also literally changing. I notice an eye or a word or a line is in a different place than where I remember seeing it years ago. Basquiat’s paintings fidget and vibrate constantly; there’s a pulse. A diagram-painting like Untitled (Hand Anatomy) (1982) is full of his signature, ‘unprecious’, late-for-the-A-train gestural strokes and the cartoon-like squiggles, lines and marks that indicate activity, movement, noise. Basquiat's scriptural gesture pleasures in and questions language's function as both textual code and visual artifact. In a deeply multidisciplinary show like Boom for Real which includes painting, graffiti, sculpture, drawing, notebooks, music, film and photography, this art lives in the meanwhile between image and text, between temporalities, between cultures, between worlds. Perhaps ambiguity is one significant way to think about the larger mission of Basquiat’s practice and one way to approach it. He is never, we are never, just one thing.

Christian Campbell is a Trinidadian Bahamian poet, essayist and cultural critic. His dedicated text ‘The Shadows’ features in the Basquiat: Boom for Real exhibition catalogue. Campbell spoke at a special event associated with the exhibition in January 2018 at Ace Hotel London.