Alona Pardo: Your new three-channel film installation Incoming (2016) advocates for a new way of looking and thinking about the representation of humanitarian crises and conflict, can you talk about your own position in relation to the subject you are documenting?

Richard Mosse: It is hard for us to begin to imagine how uncertain and traumatic these perilous journeys are for the dispossessed people who are forced to undergo them.

I chose the title ‘incoming’, not only because it evokes the idea of incoming fire – prompting a defensive ‘little Britain’ mentality of fear, currently prevalent – but also because it predicates a particular subject-object relation. The refugee is ‘incoming’ from a European perspective. I thought it was important to remind the viewer of the subjectivity within which the work has consciously been made, foregrounding this particular medium as a Western one, designed to enforce our borders and protect our nice affluent English (or German, or Italian) way of life. This approach is clearly not attempting to represent the refugee crisis in a seemingly ‘transparent’ or objective way, like classical photojournalism. Instead it attempts to engage and confront the ways in which we in the West, and our governments, represent – and therefore regard – the refugee.

AP: In order to make the work, you use an advanced technology that can see beyond 50 kilometres; can you explain how you came to use this technology and elaborate on its unique visual language?

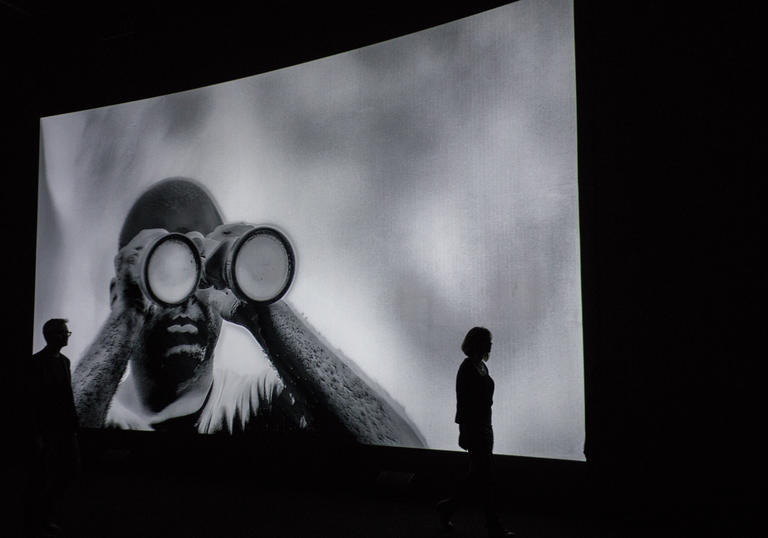

RM: The fact that this camera sees beyond 50 kilometres is not extraordinary – anyone can see the moon with their eyes, for example – but it is special in that it can detect the human body at great distances. In many ways Incoming is about the body. So, under test conditions, the camera has proven to detect the human body from a distance of 30.3 kilometres, and to identify an individual from 6.3 kilometres.

The camera itself is produced by a multinational defence and security corporation that manufactures cruise missiles, drones and other technologies. Primarily designed for surveillance, it can also be connected to weapons systems to track and target the enemy. Too large for aerial mounted systems, the camera is most suited for long-range land, coastal or maritime environments.

The camera carries a certain aesthetic violence

In spite of the camera’s coldly brutal function, our initial test shoot in London during 2014 also revealed a type of imagery that is extremely aesthetic. Quite by accident, the device produces a beautiful monochrome tonality; human skin is rendered as a mottled patina disclosing an intimate system of body heat. Yet the camera carries a certain aesthetic violence, stripping the individual from the body and portraying a human as mere biological trace. It does this without describing skin colour – the camera is colour-blind – registering only the contours of relative heat difference within a given scene. Mortality is foregrounded.

AP: Whilst Incoming charts the difficult journey migrants are often forced to make across the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa, the Heat Maps photography series that you’ve been making focuses on the makeshift camps that are springing up across Europe. What’s the relationship between these interrelated bodies of work?

RM: Well, they are the same body of work. Incoming documents the journeys and the Heat Maps such as Hellinikon Olympic Arena (2016) show the camp architecture along those routes. The Heat Maps are photographs of refugee camps that I made by attaching the thermal video camera to a robotic motion-control tripod. This rig allowed me to scan significant sites in the European refugee crisis from a high eye-level, creating extremely detailed panoramic thermal images. Each piece has been painstakingly constructed from a grid of almost a thousand smaller frames, each with its own vanishing point.

Seamlessly blended into a single expansive thermal panorama, I was surprised to find that some of the resulting images seem to evoke certain kinds of classical painting, such as those by Breughel or Bosch, in the way that they describe space and detail. They are documents disclosing the fence architecture, security gates, loudspeakers, food queues, tents and temporary shelters of camp architecture, as well as isolated disembodied traces of human and animal motion and other artefacts that disrupt each precarious composition and reveal its construction. Very large in scale, the Heat Maps delineate the intimate details of fragile human life in squalid, nearly unliveable conditions in the margins and gutters of developed economies.

The viewer engages with the work, and with aspects of the refugee crisis, in two very different modes: with the heart and with the mind…

Photography and video are really quite different forms. The video language that we evolved in making Incoming incorporates abstraction, shallow depth of field, close-up and macro detail, as well as the general sense of peering through a telescope. We slowed the footage down from 60 to 24 frames per second, so the camera lingers on details, and the viewer’s eye has a chance to wander between adjacent screens. Meanwhile Ben Frost’s soundtrack of ambient field recordings made with highly directional telescopic microphones, synthetically reworked in the studio, disorients the viewer and pushes them into a more visceral space, forcing them to respond to the work almost bodily. The Heat Maps, however, are a more passive, reflective form – dry and prosaic. I like that counteractive force, allowing the viewer to engage with the work, and with aspects of the refugee crisis, in two very different modes: with the heart and with the mind.