The Emergency shook us all ... it was a portent of things to come.

Gulammohammed Sheikh

I

In the mid-1970s, amidst rising inflation and unemployment caused by an unstable economy, labour strikes and protests spread through India against the leadership of Indira Gandhi, the nation's prime minister. She responded by declaring emergency rule over the entire country, enabled by provisions in the Indian Constitution that had been carried over from the time when the British ruled India. The Emergency ended with Gandhi's electoral defeat in 1977, but in the interim the media was censored, civil liberties were suspended and dissenting voices arrested. It was confirmed that a constitutional democracy had failed to provide economic advancement and social equality to its people. The 1977 election inaugurated an era of coalition-led governments, wherein the agendas of competing political parties would sideline the project of social transformation, which had been at the core of the founding ideals of India's democracy. These alarming circumstances prompted a range of artistic responses, some explicit in their critique of the government while others employed satire and irony.

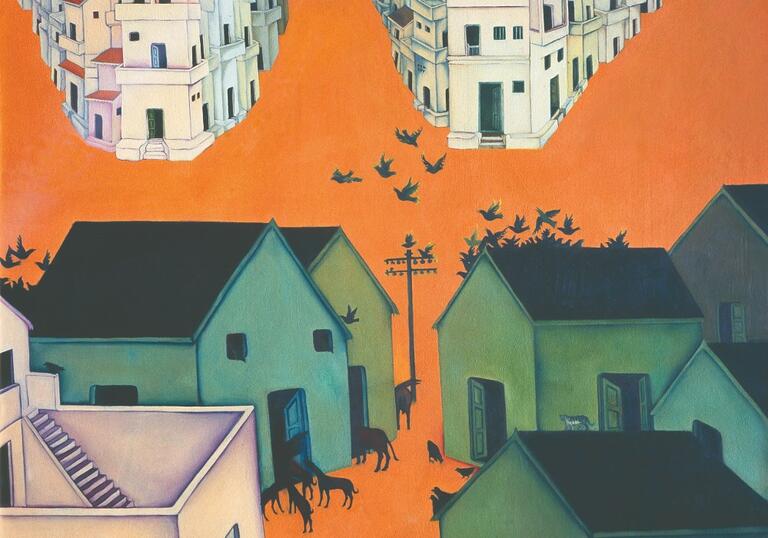

2 Gulammohammed Sheikh (b. 1937)

Speechless City, 1975

Oil on canvas

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

A forbidding glow pervades Speechless City. Foraging cattle and wild dogs huddle around abandoned dwellings in a town empty of inhabitants.

Evoking the repressiveness of the Emergency era (1975-77) and referencing the eruption of Hindu-Muslim riots in Gujarat from 1969 onwards, Gulammohammed Sheikh made this painting while teaching at his alma mater, Maharaja Sayajirao University, Baroda (Vadodara). The desolate urban landscape suggests the aftermath of an unknown, terrible event. The work originally featured a fleeing figure, which Sheikh later painted out to create a scene devoid of people.

3 Navjot Altaf (b. 1949)

Emergency Poster, 1976

Ink on paper Collection of the artist

Emergency Poster, 1976

Ink on paper Collection of the artist

As a member of the left-wing Progressive Youth Movement (PROYOM) during the Emergency, Navjot Altaf, widely known as Navjot, made these drawings in preparation for screen-printed posters. Inspired by the visual language of Cuban political propaganda, she intended the posters to be used for marches, sit ins, rallies and activists' meetings protesting against government corruption.

On display in the following bay, Navjot's Factory series depicts the dystopian landscape of the 18-month strike action by workers in Bombay (Mumbai) in 1982-83, when they defied the capitalist takeover of textile mills for building upscale housing complexes and shopping malls.

Situated between art and activism, Navjot's practice encourages collective action for structuring change and solidarity.

4 Vivan Sundaram (1943-2023)

The Indian Emergency-II, 1976-77

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

The Pair, 1976

Pastel and ink on paper

Figure from History-II, 1976

Graphite, pen and ink on paper

Gang of Three, 1976

Graphite, brush, pen and ink on paper

Oedipal Bed, 1976

Graphite on paper

Liberal Legacy, 1977

Graphite, brush, pen and ink on paper

Vivan Sundaram graduated from London's Slade School of Art in 1968, a year historically engulfed by turmoil. Influenced by Marxism, he was attracted to the post war counter-cultural spirit and its liberating vigour.

In these sketches of distorted figures and fractured realities, Sundaram's elusive and cryptic compositions evoke a dismal mood. They reference the travails of the Emergency and the accompanying crackdown on civil liberties. He combines both abstract and figurative elements, drawing on recognisable people and landscapes to elicit the entanglement between social memory and political events. In The Pair, caricatures of Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay Gandhi, who was instrumental in implementing Emergency measures, epitomise Sundaram's approach to bridging the gap between aesthetics and activism.

5 Rameshwar Broota (b. 1941)

Reconstruction, 1977

Oil on canvas

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

This satirical work was painted during the last months of the Emergency. A group of anonymised figures, hunched and ape-like, sit impotently on rows of chairs. Rameshwar Broota began making caricatures of political figures in the 1960s, soon after his graduation from the Delhi College of Art, the paintings driven by an "anxiety regarding affluence and its wastage". In a series of works made during the 1960s and 1970s, he represented the powerful and rich as broad-shouldered gorillas with diminutive heads.

In Reconstruction, these figures appear tiny and adrift at the bottom of the canvas, at risk of being swallowed up by the patterned background. While reflecting the suspension of civil liberties, Broota has highlighted the disempowerment and insignificance of the individual.

6 Arpita Singh (b. 1937)

Sunset at Kasauli, 1976

Oil on canvas

Private collection. Courtesy Talwar Gallery, New York | New Delhi

In this work a landscape of clouds and mountains emerges from Arpita Singh's tactile use of oil paint. Areas of thickly daubed pigment contrast with incisions scratched into the paint with the blunt end of a brush to reveal bare canvas below.

Sunset at Kasauli exemplifies Arpita Singh's experiments with mark-making at this time, when the artist made mostly drawings. The rhythmic, vertical lines in the work simultaneously suggest a stormy atmosphere and the weave of the canvas.

In 1976, Singh attended the first artists' workshop at the Kasauli Art Centre, where this work was made. Amid the political turmoil of the Emergency, the centre, newly founded by Vivan Sundaram, provided an informal and lively environment of artistic exchange. It remained active till 1991.

7 Pablo Bartholomew (b. 1955)

Giclee prints (archival pigment inks on baryta paper)

© Photographs by PABLO BARTHOLOMEW, All Rights Reserved

Maya, Zarine with a friend, New Delhi, 1975

Hanging out with the Maharani Bagh gang, New Delhi, 1977

Nommie dancing at a party at Koko's, New Delhi, 1975

Self-portrait, New Delhi, 1975

Rajiv and Kajoli with their daughter Meha, New Delhi, 1976

Pooh in bed, Bombay, 1975

Maya, New Delhi, 1975

A distinct mode of portraiture surfaces in these photographs made during the Emergency in India. The images, constituting a portrait of the artist's own life, reveal light-hearted moments in domestic spaces far removed from the public realm of enforcement and censorship.

Pablo Bartholomew grew up in an artistic milieu as the son of Richard Bartholomew, who was an artist, art critic and poet. "With so much confusion in my head," he says, "photography provided me with a sense of purpose and identity." Photographing the coming together of his friends, Bartholomew reveals a world in which his subjects' carefree postures and personal allure contrast with the turmoil present in daily life. These photographs were taken in Delhi and Bombay (Mumbai) alongside his regular documentary and photojournalistic practice. Despite changes in the social and political order, Bartholomew's protagonists still revel in the continuum of life.

I did not want a neutral space in which I just placed different people. I wanted the space itself to respond to the interaction between people.

Sudhir Patwardhan

II

In the years following the Emergency and through the 1980s, several artistic practices committed themselves to representing everyday life. They focused on working-class figures and how they managed their lives within changing urban landscapes. The artists Sudhir Patwardhan and Gieve Patel lived and worked in Bombay (Mumbai), and both had day jobs as medical professionals, confronting the class asymmetries and distressing conditions of the poor of the city. Bombay, with its working-class citizens and shifting social fabric, would consequently become the enduring subject of their work. Patwardhan's and Patel's figurative paintings express empathy for their subjects, whose resilience and internal strength is highlighted along with their vulnerability. The 1982-83 textile-mill strikes in Bombay resulted in disillusionment for Patwardhan and fellow artist Navjot Altaf, both Marxist ideologues. Alluding to competing social forces, Navjot's elegiac drawings and prints of abandoned mills emphasise the impact of deindustrialisation and consequent disenfranchisement of the daily-wage worker.

8 Sudhir Patwardhan (b. 1949)

Dhakka, 1977

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Running Woman, 1977

Oil on canvas

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Sudhir Patwardhan's large-scale paintings visualise the effects of urbanisation on the body of the individual city dweller and the landscape of the city.

A practising radiologist till 2005, Patwardhan uses his art to articulate stories of social struggle. His emphasis on figuration is a result of his belief in the accessibility of art for all. In the late 1970s, Patwardhan painted solidly built individuals against a minimal background; the two examples shown here were included in his first solo exhibition in 1979. Running Woman depicts a woman, "who couldn't care less as long as she caught that train", sprinting towards the viewer. Dhakka shows a labourer straining to pick up his shirt, the title (which translates to "push" in Hindi) emphasising the effort of this activity. Dignified but worn out, this subject embodies the difficult lives of the working class.

9 Navjot Altaf

Work from Factory series, 1982

Collection of the artist

10 Nalini Malani (b. 1946)

Utopia, 1969-76

8mm film animation and 16mm film transferred to video (black-and-white and colour, sound), 03:44min. Courtesy of the artist

Utopia was Nalini Malani's first experiment with film installation and combined two video projections made separately over the span of seven years, Dream Houses (1969) and Utopia (1976). She began working on Dream Houses in Bombay (Mumbai) at the Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW), an interdisciplinary exchange programme founded by artist Akbar Padamsee to foster new media practices. The work is a stop-motion colour animation which uses photographs of an architectural model made by Malani. It embodies the promise associated with the socialist aspirations of Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, towards social housing for all.

The black-and-white half of Utopia was made later, when Malani returned from studying in Paris. She filmed it from her fourth-floor apartment in a northern suburb of Bombay. Inaugurating Malani's long engagement with representations of women, a young woman looks out of a window at the slums below, which may be razed to make way for high-rise buildings. The juxtapositioning of the two films conveys disillusionment. Nehru's vision appears to have been unsuccessful as Utopia foreshadows increasing social decadence and apprehensions about urbanisation.

11 Gieve Patel

A View of the Matter, 1979

Oil on canvas

The Dabriwala Collection

12 Sudhir Patwardhan

Overbridge, 1981

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Chester and Davida Herwitz Collection, 2003. E301218. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

Town, 1984

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Chester and Davida Herwitz Collection, 2001. E301094. Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts

In the 1980s, Sudhir Patwardhan painted cityscapes constructed from multiple viewpoints. Inspired by conversations with Gulammohammed Sheikh and Gieve Patel, he looked to the flat perspectives of Indian miniature painting. All three artists were also inspired by the idea, prevalent in Chinese landscape painting, of experiencing the image as if taking a walk.

Overbridge shows a crowded metropolis: in the foreground people squeeze past each other towards the viewer; in the background, buildings jostle for pictorial space. Town features a construction scene in Bombay (Mumbai): two men examine architectural drawings in front of a half-built house, while in the background is a man with a child on a bicycle and people trade goods in the market. The building of the city intermingles with the everyday activities of its inhabitants. A variety of architectural forms, including domestic dwellings and modern high-rises, reveal the proximity of commerce, industry and private life.

The street is an extension of home, and as we know, is sometimes the only home.

Gieve Patel

III

Throughout the 1980s, artists interrogated social spaces across Indian cities, often questioning whether marginal groups and figures could make a home in the burgeoning metropolises. For them, the social spaces of a city were to be shared, accommodating a range of emotional and physical experiences, and each existing comfortably and meaningfully with the other. This fundamental concept is exemplified in Gieve Patel's operatic observation of a chaotic, crowded street in Bombay (Mumbai), where the poor and abject cross paths with the joyful and youthful; in Sunil Gupta's staged photographs of lonely gay men in Delhi, their backs turned to the camera; and in Nilima Sheikh's dreamy meditation on the domesticity of a young mother's life in Baroda (Vadodara). Each seeks to locate personal subjectivities within the Indian city. In addition to insisting upon their presence within urban vistas, the works also render the subjects as figures with interior lives that deserve attention and respect.

13 Gieve Patel

Off Lamington Road, 1982-86

Oil on canvas

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

This epic painting captures a crowd moving through a busy alley, located off an important road in Bombay (Mumbai) where Gieve Patel worked as a doctor.

Across the painting, men and women stand or squat in small groups to talk. On the right, musicians accompany young people dancing, some dressed in colourful clothes. Celebration is side-by-side with destitution: two bandaged, leprous children beg for alms, and a woman lies naked and bleeding in the foreground. Patel's work often depicts people on the fringes of society. The painterliness with which these figures are portrayed verges on abstraction, conveying the transience of the crowd.

Patel was driven to paint a crowd after seeing Pietro Lorenzetti's Crucifixion (c.1340s) in Italy. Here, the three vertical shafts of the buildings in the background, each in a different architectural style, echo the three crosses in Crucifixion.

14 Nilima Sheikh (b. 1945)

Before Nightfall, 1981-82

Oil on canvas (triptych)

Private collection

Before Nightfall is a surreal painting of a neighbourhood scene that unfolds in a triptych. Nilima Sheikh made this painting while living and working in Baroda (Vadodara), and represented in it is the university campus that surrounded her, including the old Residency Bungalow, a constituent motif across other works from this period. Recalling the hour when she accompanied her children on their evening outings, Sheikh painted a girl who often played with them around the house.

Filled with changing light and exuberant expressions of movement, the work alludes to the transition from day to night. A sense of mutation emanates from the canvas, suggesting the interim moment before electric light takes over the darkness. Across the three panels, the artist's domestic environs spill into the natural world of flora and fauna, illustrating the symbiotic relationship between humans and other forms of life. In an act of self-expression and perhaps feminist assertion, Sheikh gives visibility to the world of motherhood.

15 Sunil Gupta (b. 1953)

Exiles, 1987

Archival inkjet prints

Courtesy the artist and Hales London and New York. © Sunil Gupta.

India Gate

Humayun’s Tomb

Indira's Vision

Connaught Place

Jangpura

Hauz Khas

Nehru Park

Lakshmi

Staged amongst famous New Delhi landmarks and some cruising sites, these constructed images present the complexities faced by gay men when homosexuality was still a punishable offence in India. Section 377, a colonial law enacted in 1861, criminalised homosexuality and was only repealed by India's principal court in 2018. The series was realised in 1986-87 through a commission awarded by The Photographer's Gallery, London, and was for Sunil Gupta "about locating Indian cis men in an international gay landscape". Born in New Delhi, the artist moved to Canada in 1969 at the age of 15. He relocated to the United States prior to settling in London.

Accompanied by excerpts of conversations with his subjects, all voluntarily offered, the colour photographs reveal the sentiments of gay Indian men and their vulnerable, clandestine lives. Gupta ensured he had the consent of his subjects to print the photographs, with the understanding that the images would not be shown at the time in India. Finally, in 2004, Gupta exhibited Exiles at the India Habitat Centre in New Delhi as a belated, affirmative homecoming.

Two Men in Benares was painted when I think I needed courage. All the time I sought courage.

Bhupen Khakhar

IV

As artists explored how to situate individuals facing societal prejudice and discrimination within the larger frieze of the Indian city and town, they began to experiment with spatial structures to give expression to internal lives, desires and dreams. Multiple narratives unfold simultaneously in their works, with figures embedded in landscapes which offer numerous shifts in perspective. Such an aesthetic strategy stresses that a plurality of experiences can co-exist, projecting a world view that is inclusive and affirmative. For Bhupen Khakhar, “The act of painting turned to [the] act of making love. That is why I started it … I add my fantasy to real relationship and also in my painting.” The sacred and the sexual co-exist within his social landscape, providing room for masquerade, a jolly romp, and the possibility of a polymorphous universe. As provocative challenges, these works channel the tension between the private fantasies of women or the erotic reveries of queer men and the moral judgement of the public realm. As Arpita Singh affirms, “What is a dreamlike, imaginative world to you is a real world for me.”

16 Bhupen Khakhar (1934-2003)

In a Boat, 1984

Oil on canvas

Shumita and Arani Bose Collection, New York

17 Bhupen Khakhar

Two Men in Benares,1982

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Bhupen Khakhar, an accountant by training, was a self-taught artist who took to painting in the 1960s. His early works comprised portraits of tradesmen. In 1980, he began to address his homosexuality, which he had struggled with until then.

In this dramatic painting, the intertwined nude lovers are set against a blue background with numerous vignettes unfolding around them. Such narrative representation reveals Khakhar's interest in 14th-century Sienese painting, especially the work of Ambrogio Lorenzetti. Khakhar integrates the lovers into the quotidian reality of the hallowed city of Benares (Varanasi), with its holy men, small shrines and kneeling devotees. By staging this sexual tryst within a religious context, he knowingly props up the erotic against the sacred, and provocatively collapses the boundaries between private and public.

First exhibited at Gallery Chemould, Bombay (Mumbai), in 1987, the painting had to be stored away just two days later for fear of protests from the Central Cottage Industries Emporium, in whose premises the gallery was located.

18 Arpita Singh

The White Peacock, 1985

Oil on canvas

Shumita and Arani Bose Collection, New York

In a marked departure from her earlier near-abstract, tonally muted work, Arpita Singh's paintings of the mid 1980s feature people, chintz-covered armchairs, birds, flowerbeds and aircraft floating on a plane of pure blue. With their strange scale and disorienting spatial organisation, they inhabit the realm of fantasy. A dreamlike logic liberates familiar, everyday objects from the rules of reality, transforming them into symbols which evade interpretation.

In The White Peacock and in Seashore (on display nearby), dreaming is a form of inner political resistance. It is beyond the control of the outer authority of the state. Singh's paintings express yearning, the expanse of vivid blue in both paintings recalling open sky or ocean. The white peacock, here mythically oversized, is emblematic in Indian culture of an absent lover. Vibrant and playful, these two works subvert the domestic environment towards a liberated desire.

I was powerfully affected by the struggle against the violence against women ... I became part of it.

Sheba Chhachhi

V

In 1974, the government report Towards Equality stated that women were “far from enjoying the rights … guaranteed to them by the Constitution”. Women’s movements spread across the country to protest social laws and gender-based violence. Simultaneously, as Nilima Sheikh recalls, “Those were the early years of recognition of feminism within the practice of art in India.” Some works, such as Sheba Chhachhi’s photographs of anti-dowry protests in Delhi, were tethered closely to feminist activism. Others explored societal attitudes and mores that actively inhibited the broader participation of women in civil society. Alongside were those artists who did not identify as feminists, but made work that resonated with feminist politics. Formally, all these artists developed individual visual iconographies to occupy distinct positions with, at times, differing priorities, confirming that the reality of women in India could not be reduced to a single issue or aesthetic. The artists shared allegiances, but also frictions, making work that stretched from the street to the home, from sexual violence to pleasure and friendship.

19 Arpita Singh

Seashore, 1984

Oil on canvas

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

20 Sheba Chhachhi (b. 1958)

Seven Lives and a Dream, 1980-91

Digital C-type prints on paper

Courtesy of the artist

Sathyarani -Anti-Dowry Demonstration, Delhi, 1980

Sathyarani - Staged Portrait, Punjabi Bagh residence, Delhi, 1990

Sathyarani - Staged Portrait, Supreme Court, Delhi, 1990

Radha - Staged Portrait Set-up, Anandlok, Delhi, 1991

Radha - Staged Portrait, Anandlok, Delhi, 1991

Devikripa - Staged Portrait, Seemapuri, Delhi, 1990

Devikripa - Sit-in, Family Planning Centre, Nandnagari, Delhi, 1998

Devikripa - Sikh Widow, Trilokpuri, 1987

Shanti - Staged Portrait, Dakshinpuri, Delhi, 1991

Shanti - With Children, Dakshinpuri, Delhi, 1989

Urvashi - Staged Portrait, Gulmohar Park, Delhi, 1990

Urvashi -Anti-Dowry Sit-in, 1982

Urvashi - Street Play, 'Om Swaha: Mehrauli, Delhi, 1982

Shardabehn - Public Testimony, Police Station, Delhi, 1988

Shardabehn - Staged Portrait, DTC Bus Terminus, Delhi, 1990

Shahjahan Apa - Anti-Dowry Public Testimonies, India Gate, Delhi, 1986

Shahjahan Apa - International Woman’s Day Gathering, Dakshinpuri, Delhi, 1980

Shahjahan Apa - Staged Portrait, Nangloi, Delhi, 1991

Shahjahan Apa - Staged Portrait Set-up, Nangloi, Delhi, 1991

Sheba Chhachhi's series of 19 black-and-white photographs follows seven women activists. Chhachhi became involved with the women's movement when she returned to her hometown of Delhi in 1980 after completing degrees at the Chitrabani Centre for Social Communication, Calcutta (Kolkata), and the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad. Amidst a wave of protests against dowry-related violence, Chhachhi photographed her fellow campaigners, the tightly focused images emphasising their emotional intensity.

While these images were initially intended for circulation within the movement, Chhachhi felt the need to move beyond documentary photography - a form in which "the power of representation" always remains with the photographer. She also felt that the single image could not adequately capture the complexity of the women, whom she knew personally.

Almost a decade later, Chhachhi invited the same women to collaborate on a series of portraits, in settings and with props of their choosing. Satyarani chose to be depicted on the steps of India's Supreme Court, the location of her decades-long battle for justice for her murdered daughter. Many of the women were photographed within their homes, the private, domestic realm sitting alongside the public forum of street protests. The props - books, family photographs, typewriters, grain - allude to facets of the sitters' identities, from which emerges an image of the movement that united women across class lines.

21 Nilima Sheikh

When Champa Grew Up, 1984-85

Tempera on Sanganeri paper

On loan from Leicester Museums and Galleries

This series of 12 narrative paintings on handmade paper immerses the viewer in the life of Champa, a teenager. At first, she appears as an idealistic girl, her bicycle a symbol of independence. In the following images, however, she is married off while still a child and subjected to abuse in her new home. The series culminates in her dowry-related murder by her husband and parents-in-law.

Nilima Sheikh knew the young girl in real life and deliberated upon how to represent her tragedy. The artist explains that she moved away from wall painting because she "didn't want to trivialise Champa's fragile story". The vivid realism of Indian miniature painting, particularly in traditions from the Punjab hills, as well as in East Asian scrolls, informed her method of creating a narrative that unfolds laterally in the unbound series of images.

I was looking for my own way to myself, rooted in the great Indian tradition.

Meera Mukherjee

VI

While the burgeoning metropolis and developing mid-sized town became subjects for a number of artists in the 1970s and ‘80s, others looked to the cultures of Indian villages. To engage with the creative traditions of rural communities, urban artists had to acknowledge their own privileged status. They had to maintain a critical distance when observing how they combined their own artistic knowledge with artisanal and craft traditions. Jyoti Bhatt and Meera Mukherjee took what could be judged as an anthropological approach, committing themselves to extensive research and documentation. Mukherjee would then eventually develop her own lost-wax technique from observing artisanal working processes in Bastar. Madhvi Parekh, on the other hand, with no formal training, formulated a visual idiom by drawing on her memories and lived experiences of growing up in a Gujarati village. Finding inspiration in village cultures involved self-awareness and a complex reconciliation for these artists, compelling Mukherjee to state that "like an artisan, an artist must learn to work without cease. He must in fact work harder."

22 Madhvi Parekh (b. 1942)

Happy in the Village-1, 1982

Oil on canvas

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Village Opera-2, 1975

Oil and oil pastel on canvas

Private collection

Madhvi Parekh's oil paintings depict remembered landscapes from both her childhood village of Sanjaya, Gujarat, and her subsequent travels. She painted Village Opera-2 after attending an artist's camp organised by artist G. R. Santosh in Kashmir in 1975. The copper pots she saw there inspired the black anthropomorphic figures at the centre of this work. Working first with oil paint, Parekh then used oil pastels to add small, vibrant creatures which resemble birds, fish, snakes and amphibians. The scene floats in a colourful net of dots and lines, patterns drawn from the folk crafts of Rangoli and embroidery that she had practised as a child.

Childhood memory also informs Happy in the Village-1, which depicts the farm Parekh passed on her daily walk to and from school. Farmers relax in the heat of the afternoon, surrounded by their animals.

Initiated into art by her artist husband Manu Parekh, Madhvi Parekh began to paint only after leaving Sanjaya, and with memory as their subject, her paintings provide a way back to the idyll of village life. "I have never forgotten the sights and sounds of my village," she says. "I carry them with me everywhere and, although they are often combined with elements I have imbibed in the city, they still endure."

23 Jyoti Bhatt (b. 1934)

Silver gelatin prints

Collection Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru

Women from Haryana making Sanjha images at a craft village, New Delhi, 1977

Untitled, Rajasthan, 1989

A Rathwa tribal house, Gujarat, 1980

Black Lamp, West Bengal, 1980

A niche on a wall of a Rajawar's house, Surguja, Chattisgarh, 1983

Madhya Pradesh, 1983

Rajasthan, 1988

A chulha in a courtyard kitchen, Rajasthan, 1981

A Rajasthani artist next to her wall painting at the Crafts Museum, New Delhi, 1987

Detail from a wall decoration inside a tribal house, Madhya Pradesh, 1980

Painter, printmaker, photographer and educator, Jyoti Bhatt was among the first generation of art students at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda (Vadodara) to reflect on questions of tradition, modernity and cultural identity in post-independence India. Made in association with rural Indian communities, these photographs show Indigenous artists creating wall and floor paintings that reflect the relationship between their folklore and culture and their surroundings.

Bhatt's photographs archive the disappearing traditions of the country, a consequence of the rapid urbanisation and economic development that began in the 1960s, and were prompted by a trip to Gujarat in 1967 with Sheikh and Bhupen Khakhar to collect art objects for a seminar on folklore in Bombay (Mumbai). Travelling for almost three decades through the rural heartlands of Haryana, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha and West Bengal, Bhatt documented the decorative traditions of Rangoli and Kolam design-making, Kantha embroidery, Bhil tattoos, Mandana drawing and Pithora painting.

24 Meera Mukherjee (1923-1998)

Untitled (Smiths Working Under a Tree), n.d.

Bronze

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

People in a Row, c. 1980

Bronze

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Pilgrims to Haridwar, n.d.

Bronze

Tia Collection, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

Untitled (Andolan), 1986

Bronze

Tia Collection, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

Trellis, n.d.

Bronze

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Meera Mukherjee sought a modernism that would articulate an Indian national identity in the aftermath of British colonisation. Educated at the Delhi Polytechnic College and the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich, she rejected their curriculums which adhered to the western canon of modern art.

A grant from the Anthropological Survey of India provided the opportunity to work with Gharua craftsmen in Bastar in central India. She travelled widely, studying the metal-casting techniques of Dhokra artisans in West Bengal, Khoruras and Ghantrars in Odisha, and Sakya craftsmen in Bhaktapur, Nepal. This composite tradition informed Mukherjee's own use of lost-wax casting, in which a wax model is used as a mould for molten metal. When cooled, the sculpture is finished by hand.

Inspired by the devotion with which craftsmen attended sacred subjects, Mukherjee approached the ordinary with similar spiritualism. Small-scale and intricately detailed, Mukherjee's sculptures elevate figures from everyday village life: labouring artisans in Untitled (Smiths Working under a Tree), students in mass protest in Untitled (Andolan), and religious devotees in Pilgrims to Haridwar. Configured in compositions at once rhythmic and organic, these figures from the contemporary world appear subject to larger, celestial forces.

25 Pablo Bartholomew

Giclee prints (archival pigment inks on baryta paper)

© Photographs by PABLO BARTHOLOMEW, All Rights Reserved

Union Carbide signage smeared in red paint, 1984

20 years after; inside the premises of the Union Carbide Factory, 1984

Livestock that became victims of the Bhopal gas leak, 1984

A child killed by the Union Carbide gas leak, 1984

Pablo Bartholomew's iconic series of photographs conveys the grim realities that unfolded in 1984 when massive amounts of toxic gas leaked from the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. Recognised as the world's worst industrial disaster, air contamination killed thousands while inflicting lifelong illnesses and critical diseases on another half-million residents and unborn children. Bartholomew documented the incident and its aftermath for over 20 years: a father buries his daughter; a Union Carbide sign is vandalised in protest; dead livestock are left to decompose on open land; and bags of poisonous chemicals are abandoned in rusting warehouses.

Today, the site exists as a hazardous wasteland with cleaning-up processes facing multiple and extraordinary challenges. The groundwater around the factory area is still dangerously contaminated.

We cannot by any device of mental gymnastics relegate our Adivasi communities to the past ... They are living expressions of living peoples ... we cannot but treat them as contemporary expressions.

Jagdish Swaminathan

VII

On gaining independence, the Indian state dedicated itself to numerous modernising projects, but neglected to establish a well-considered Indigenist programme. In the 1960s, sensing discontent, the government inaugurated a series of initiatives and institutions to document and survey folk-craft traditions, which dovetailed with the art community's interest in rural aesthetic traditions. A central figure in these exchanges was Jagdish Swaminathan, who warned that "the tribal and pastoral communities in India are too numerous to be liquidated in the 'natural' process of economic evolution." Appointed the founding director of the multi-arts complex Bharat Bhavan, inaugurated in 1982 in Bhopal, he innovatively exhibited "contemporary folk, tribal and urban art", opting for the Hindi word "Adivasi" (original inhabitants) over terms such as "primitive", and refused ethnographic or anthropological modes of display. He advocated for a "symbiotic approach, which could possibly be the catalyst for both the so-called tribal communities and us to emerge into a new world of freedom", asserting that "contemporaneity" was a dialogue between the primordial and the modern, a "simultaneous validity of co-existing cultures".

26 Jagdish Swaminathan (1928–1994)

Untitled, 1993

Oil on canvas

Tia Collection Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

Untitled, 1993

Oil on canvas

Tia Collection Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

Untitled, 1992

Mixed media on canvas

Private collection

These paintings by Jagdish Swaminathan are reminiscent of the geometric shapes, broad swathes of colour, and figuration and abstraction found in Indian folk art, Tantric inscriptions, and local crafts and textiles. Swaminathan applied pigments with his fingers in multiple layers of thinned oil paint, which merged into symmetrical, patterned forms.

His post-colonial approach, which blended tradition with modernism, stemmed from time spent first as a political member of leftist organisations and then as an art critic. Departing from realist depictions of pastoral subjects, Swaminathan chose to foreground the natural and the mystical. These works, with their tribal motifs, ritual diagrams, and angular forms drawn from ancient scriptures, imbue modernist colour fields and grid structures with spiritual themes.

27 Jangarh Singh Shyam (1962-2001)

Giddhilli Pakshee, 1989

Ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Goh, 1989

Pen and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Bicchi, 1990

Pen and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Mashwasi Dev, 1989

Ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Tattoos (Godna-1), 1990

Pen and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Tattoos (Godna-2), 1990

Pen and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Raksha, 1992

Ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Ratmai Murkhudi, 1993

Ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Chatu Pakshi, 1994

Pen and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Ratmai Murkhudi, 1983

Acrylic on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Khairaagadaheen Devi, 1983

Acrylic on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Chachan and the Snake; a gigantic eagle swooping down on a snake, 1997

Pen and ink on paper

Collection Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru

Untitled, 1994

Pen and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, 1997

Ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

A member of the tribal Pardhan clan of Patangarh, Jangarh Singh Shyam reinterpreted his community's customs, oral traditions, rituals and myths to create a unique mode of expression. His works depict deities and daemons alongside elements from the natural world, including serpents, birds, crocodiles and stags.

In 1980-81, the teenaged Shyam came to the notice of a team of artists sent by Jagdish Swaminathan from Bharat Bhavan. At Bharat Bhavan's graphics studio, Shyam gained access to bright poster paints and acrylics, white paper and canvases, and Rotring pens, meant for technical drawing. With these materials and Swaminathan's support, his practice came to encompass drawing, printmaking and mural painting.

Shyam's works are refracted through memories of his village and suffused with a sense of nostalgia and loss. This stemmed from his own migration to Bhopal and the broader threat, posed by the country's economic transformation, to the traditional lifestyle of Indigenous communities. The artworks here reflect how Indigenous art practices have always adapted in response to new materials and environments, undermining perceptions of these traditions as frozen in the past.

The artist died by suicide in 2001, while on a residency at the Mithila Museum in Japan.

28 Himmat Shah (b. 1933)

Untitled, c. 1997-98

Terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, n.d.

Terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, c. 1982

Terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, n.d.

Terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, c. 1997-98

Terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, n.d.

Terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Himmat Shah began sculpting heads from clay after attending an artists' camp at the Garhi studios in New Delhi in 1976. Using the slip-casting method, he poured viscous clay into plaster moulds, and as it dried, the clay was absorbed by the plaster, resulting in unexpected fractures, cracks and holes in the surface of the work. Shah emphasised these qualities through marks made with tools that he designed himself. Often, he added a dot as a humanising detail and a focal point for the gaze.

Shah's use of terracotta, which he describes as an ancient material, was inspired by his birthplace of Lothal, Gujarat, one of the sites of the Indus Valley civilisation. As a child, from 1955 to 1966 he saw the Archaeological Survey of India excavating for ancient pottery and made clay toys at a nearby potters' studio. These experiences as well as memories of dried-up lake beds and routes traced by insects over parched surfaces inform Shah's terracotta sculptures. He "took an ancient material and brought it forward to give it a contemporary edge."

Indianness cannot be a matter of form alone. It was to be a matter of intention, of perception ...

Safdar Hashmi

VIII

Over the course of the 1970s and 1980s, a mode of figurative narrative painting gained prevalence as a second generation of post-independence artists grappled with the changing urban landscape and various social issues. There were also artists who worked outside of and at times rallied against these aesthetic parameters. Though they attested to the diversity of artistic practices operating in India at the time, not all received equal visibility or commendation. The Indian Radical Painters' and Sculptors' Association, formed at the Faculty of Fine Arts, Baroda (Vadodara), had misgivings about the "bourgeois-centred Indian art world". The association was led by K. P. Krishnakumar and most of its members had been initiated into leftist politics in their home state of Kerala. In Delhi, activist Safdar Hashmi, murdered in 1989, used street theatre as a form of protest and act of resistance. Savindra Sawarkar was unique in forming a distinct visual iconography to address the plight of the Dalit community. The motivation behind these artists' practices was to expose the pervasive oppression and discrimination in Indian society, based on class and caste.

29 Savindra Sawarkar (b. 1961)

Untouchable, Peshwa in Pune, 1984

Etching on zinc plate

Collection of the artist

Untouchable with Devadasi III, 1985

Etching

Collection of the artist

Peshwa, 1985

Etching on zinc plate

Collection of Gary Michael Tartakov and Carllie C. Tartakov

Devadasi with Crow, 1985

Etching

Collection of the artist

Untouchable with Dead Cow, 1989

Drypoint on zinc plate

Collection of the artist

Brahmin and Devadasi with Dhamma Chakra, 1995

Drypoint on copper plate

Collection of the artist

Savindra Sawarkar's etchings are concerned with Hindu society's singular persecution of Dalits, who, at the bottom of the caste-based Brahmanical hierarchy, are categorised as "untouchable".

Sawarkar portrays humans and animals alongside each other, at times in a biomorphic relationship. Some works depict "devadasis", dancers and musicians who are offered as young girls to a temple for their entire lives. Often subjected to sexual exploitation, devadasis are drawn overwhelmingly from Dalit communities. Other works show Dalit men shouldering the carcasses of cows, a reference to the historically lower-caste profession of tending to corpses.

Sawarkar explains that the "visual markers of the Dalit experience - the matka (pot) and jhaadu (broom) - became part of my work right from my art school days." Under medieval Peshwa rule, Dalits had to collect their spit in the pot and sweep away their footprints. This is the subject of Peshwa and Untouchable, Peshwa in Pune, in which Sawarkar's dark, inky lines, etched repetitively into the printing plate, form shadows which threaten to engulf the Dalit men and women.

30 N. N. Rimzon (b. 1957)

From the ghats of Yamuna, 1990

Terracotta pots, marble and fibreglass

Courtesy of the artist and Talwar Gallery, New York | New Delhi

Like other artists, the young N. N. Rimzon too was impacted by the Emergency, electing to move away from painting to sculpture. The College of Fine Arts in Trivandrum (Thiruvananthapuram), Kerala, where he met K. P. Krishnakumar, exposed him to Marxism and leftist literature in his formative years.

This work was made shortly after Rimzon returned from the Royal College of Art, London, when he was exploring how "materials evoked psychic memories and feeling". He scouted the streets of Delhi for earthen pots at a time when the use of found objects in sculptural work was uncommon in India. Nestled between the two conjoined pots is a white house, and the title refers to the steps lining the banks of the River Yamuna, by which people descend to the sacred waters to engage in ritual cleansing.

The interaction between the home and the sacred, the connection between the ancient and the modern, and a harmonious balancing of different elements became the enduring preoccupations of Rimzon's work.

31 M. F. Husain (1915-2011)

Safdar Hashmi, 1989

Acrylic on canvas

Emami Group of Companies

This work represents the killing of political activist, actor and playwright Safdar Hashmi (1954-1989), who M. F. Husain paints with broken limbs, reinforcing the brutality of the attack. Hashmi had been performing a street play in a village outside Delhi.

A pioneering figure in Indian theatre, Hashmi founded the Jana Natya Manch (or "people's theatre forum", known popularly as Janam), which staged plays in public spaces and working-class neighbourhoods to counter attempts by the ruling class to suppress dissent. His murder evoked widespread condemnation of the growing violence in Indian politics. After his death, artists, activists, and intellectuals came together to form the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust (SAHMAT), an advocacy cooperative committed to promoting democratic values and secularism through art.

Husain championed India's pluralistic identity in his paintings, intertwining modernist concerns with depictions of national idols. From 1996 onwards, he was accused of obscenity and offending the religious sentiments of the Hindu populace. Despite receiving the support of various civil society groups, including SAHMAT, and winning a related court case, threats to his life from a Hindu nationalist group forced him to leave India in 2006.

32 K. P. Krishnakumar (1958-1989)

Untitled, 1982

Brush and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, 1982

Brush and ink on paper

Collection and image courtesy Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

The Good Samaritan (After van Gogh), 1982

Brush and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, 1983

Brush and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled (The Pond Near the Field), c. 1982

Brush and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Untitled, 1982

Brush and ink on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

The events of the Emergency spurred K. P. Krishnakumar to create art which directly addressed conditions of marginality and oppression. A commitment to Marxist politics was also central to his work, shared by fellow artists of the Indian Radical Painters' and Sculptors’ Association (the Radical Group). Among them were Anita Dube and C. K. Rajan, whose works are also on display later in the show.

With his charm and charisma, Krishnakumar galvanised the group's resistance against the narrative, figurative approach to painting that came to be associated with the Baroda Faculty of Fine Arts. Searching for a more "international" art, the group was particularly interested in inter-war German Expressionism. This influence can be discerned in Krishnakumar's drawings, which utilised a brush dipped thickly in black India ink for bold mark-making.

These wild and frenzied drawings, some of which are self-portraits, depict muscular figures, animals, rural landscapes and domestic interiors caught up in the rhythms of daily toil. Anita Dube described them as projecting "an abjection" and strongly communicating a "lack in terms of class, race and sexual difference", where "human dramas unfold within this unhomely world". The Radical Group disintegrated upon Krishnakumar's death by suicide in 1989.

33 K. P. Krishnakumar

Boatman-2, 1988

Fibreglass sculpture

Courtesy of Ark Foundation for the Arts, Vadodara

This sculpture by K. P. Krishnakumar takes the male body as its subject. Working in fibreglass, which he covered with cloth and plaster, the artist patinated and moulded its surface to resemble cast metal.

Boatman-2 is a reworking of an earlier sculpture which perished in a fire. In both versions, a fisherman's body melds with his boat. Conjoined with the tool indispensable to his livelihood, the fisherman becomes a seemingly unfinished hybrid of man and machine, alluding to a destabilised personhood. The resultant figure is unreadable and impassive, gazing ahead at an imagined horizon. In his work, Krishnakumar sought to transcend regional, individual identity. Defying narrative and driven by the need to make art political, Krishnakumar's work locates struggles of race and class in the universal body of the labourer.

It’s necessary to emerge from our insular shells, to come together and try and develop symbols of secularism.

Rummana Hussain

IX

On 6 December 1992, an organised mob of Hindu activists demolished a 16th-century mosque, the Babri Masjid, in Ayodhya, India. They contended that the mosque had been built upon the site of a Hindu temple that had commemorated the birthplace of the god Ram - a mosque-temple debate ongoing since the 19th century. The destruction of the mosque triggered riots across the Indian subcontinent, in which some thousands were killed. This communal violence had a profound impact on many members of India's artistic community. Vivan Sundaram recalled that there was "enormous despair", which "shook the belief system of those brought up with Nehruvian ideals of secularism. There was a crisis." Several artists were compelled to make works in response, and some, such as Rummana Hussain and Sheela Gowda, radically re-oriented their practices. It was within this context that artists began to experiment with installation, cross-media and performance in an effort to directly address issues of secularity and to deconstruct essentialised ideas about India's modern and pre-modern past.

34 Tyeb Mehta (1925-2009)

Durga Mahisasura Mardini, 1993

Acrylic on canvas

Mr. Lakshmi Niwas Mittal and Mrs. Usha Mittal

In this work by Tyeb Mehta, the Hindu goddess Durga slays the buffalo demon Mahisasura as he transforms into human form. Referencing classical Indian mythology, the theme of good vanquishing evil provides a hopeful allegory in a time of social and political turbulence.

Mehta painted this work in the year following the demolition of the Babri Masjid. As a Muslim, he was impacted by the horrors of the communal violence which ensued in Bombay (Mumbai), where he was living. Throughout his life, Mehta advocated secularism, which he believed was necessary for social unity.

The work depicts Durga as a serene figure triumphing over the threat of disharmony. Bulls were a common motif in Mehta's work, and he once commented that he saw them as "representative of the national condition ... the mass of humanity unable to channel or direct its tremendous energies".

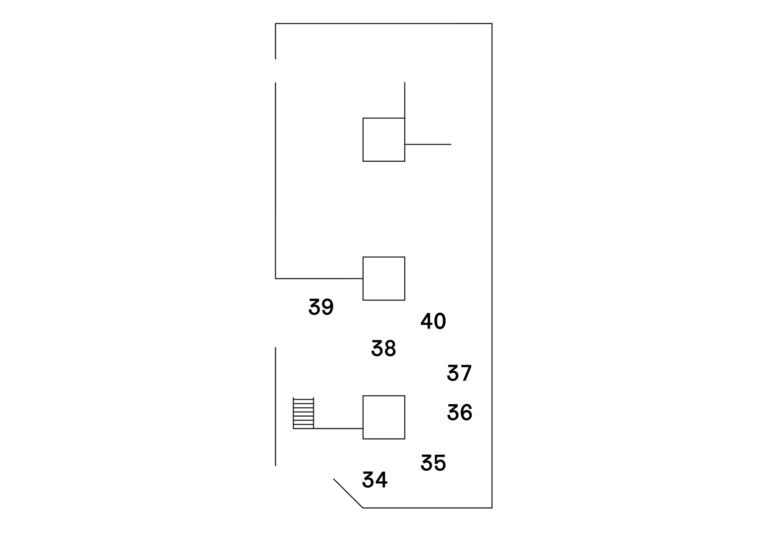

35 Rummana Hussain (1952-1999)

Conflux, 1993

Wood, paint on acrylic, gheru, terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Dissected Projection, 1993

Wood, mirror, terracotta, acrylic, earth, wall-mounted pot, wooden box, acrylic box

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Resonance, 1993

Wood, mirror, paint on acrylic, plates, rice, water, rock, shell

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Fragment from Splitting, 1993

Bricks, mirror, gheru, terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Unearthed, 1993

Bricks, wood, terracotta

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

These five works by Rummana Hussain were among her first installations. Having painted figuratively to express the political throughout the 1980s, she felt the need for object-oriented art which could respond to immediate realities.

When the Babri Masjid was demolished in 1992, Hussain was living in Bombay (Mumbai), one of the cities worst affected by communal riots. As a Muslim woman, she was forced to temporarily flee her home with her family.

Emerging from this traumatic experience, the works displayed here, in which the shattered terracotta pot is a recurrent motif, were in her first solo show, 'Fragments/Multiples', at Bombay's Gallery Chemould in 1994.

Hussain used the pot allegorically: the shards of terracotta resemble broken domes, destroyed homes, and the human body undone, each alluding to the violent fracturing of social unity. From these pots, everyday materials, such as gheru (a powdered red clay) and rubble, spill onto mirrors. Their reflections are interrupted, distorted, evoking a desolate landscape of ruins.

36 Arpita Singh

My Mother, 1993

Oil on canvas

Property from the Collection of Mahinder and Sharad Tak

Arpita Singh's monumental painting, My Mother, records the chaos of communal violence exploding across India in the early 1990s. The artist's mother looms dignified and stoic in the foreground, while militiamen in bottle-green uniforms enact scenes of devastation behind. Shrouded bodies line the streets and victims lie stripped on the ground.

Motifs which represented the home in Singh's earlier paintings now take on darker characteristics: flowers become funerary while blue crosses, resembling the decorative stitching of Kantha work, mark houses as targets. (The folk craft of Kantha is a type of quilting practised by women in Bengal, where Singh was born. Often richly ornamented, it is produced for domestic use.) Chairs, referred to by the artist as "the most familiar object of my environment", appear upturned and strewn across the canvas.

Singh had started work on a portrait of her mother when riots erupted in Bombay (Mumbai). Unable to keep these two elements from spilling into one another, the painting represents collapsing boundaries between home and nation, private and public, and the real and the imagined.

37 Rummana Hussain

Behind a thin film, 1993

Left: Indigo and earth pigment, acrylic on printed paper, collage and tracing paper pasted on paper. Right: Acrylic on print collage, ink on plastic sheet, charcoal and Xerox on paper

Estate of Rummana Hussain. Courtesy Talwar Gallery, New York | New Delhi

Dissemination, 1993

Indigo and earth pigment, ink, charcoal and print on paper

Estate of Rummana Hussain. Courtesy Talwar Gallery, New York | New Delhi

Tower of Babel,1993

Terracotta and print on plexi, acrylic, indigo, earth pigment, pastel and print on plastic, board

Estate of Rummana Hussain. Courtesy Talwar Gallery, New York | New Delhi

These mixed-media works on paper represent Rummana Hussain's transitioning phase between painting and installation. Moving away from paint towards indigo, earth, charcoal and terracotta, she experimented with "domestic materials which are related to a woman's everyday experience". Speaking in 1994, Hussain stated, "I am also a woman who spends a lot of time in my house - in my body. The house is a body." This bodiliness is present in the application of the pigments, which she rubbed into the creases and folds of crumpled paper.

In Dissemination, the pigments are collaged with words, such as "embryo", '"organ" and "rupture", appropriated from newspapers. In Behind a thin film, multiple photocopies of a newspaper photograph, depicting Hindu militants atop the Babri Masjid's dome, become delicate abstractions. In Tower of Babel, printed images of the warrior goddess Durga appear alongside a fragmented grid and a shattered terracotta pot, anticipating Hussain's installation works that are on view nearby.

38 Vivan Sundaram

House, 1994

From the series Shelter, 1994-99

Kalamkhush handmade paper, steel, wood, water, glass, brake grease, acrylic paint, video

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Vivan Sundaram transitioned from painting and drawing in the early 1990s to embrace a broader, spatially oriented approach. House portrays his reflections on the changing political landscape and communal tensions in India at the time.

Held by a metal armature, the installation elaborates on the concept of refuge. A walled sanctuary cast in kalamkhush (paper handmade from khadi, the hand-spun, natural-fibre fabric promoted by Mahatma Gandhi during India's anti-colonial struggle), House's surface carries embossed emblems of the tools of labour and speaks to collective struggles against power.

Alongside a mineral hue reminiscent of coagulated blood, the outer walls exhibit marks of brutality: scattered limbs, jagged outlines of weapons, and closed windows. Within, a pedestal bears a wide-brimmed vessel filled with water, and flickering through the transparent base of the bowl, a fiery video projection conveys an allegory of simmering injustice.

39 Gieve Patel

Battered Body in Landscape, 1993

Oil on canvas

Shumita and Arani Bose Collection, New York

In this haunting work by Gieve Patel, an eyeless, brutalised figure lies exposed in a barren landscape. As with Rummana Hussain's terracotta shards and Vivan Sundaram's blood-stained walls, both on display nearby, Battered Body in Landscape depicts the aftermath of violence, rather than the violent act itself.

The figure within a landscape is an important motif in Patel's works, as seen in Two Men with Hand Cart and Off Lamington Road, but in these earlier works the subjects were relaxed, joyous, intimate or despairing. Here, in a dramatic shift of mood in response to the events of the early 1990s, the figure is bereft of life.

Soon after Patel finished the painting, a close friend of his passed away. "It was impossible for me to dissociate the two things from each other," the artist has said. "Every time now that I pick up a canvas to work on themes like this I face a kind of terror - am I actually letting loose certain forces?"

40 N. N. Rimzon

The Tools, 1993

Resin, fibreglass, marble dust, iron

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi, India

N. N. Rimzon, whose practice was already sculptural, began turning towards a more installation-based approach, as many other artists did in the 1990s. In The Tools, a figure stands in a state of meditation. Rimzon derived the pose from sculptures of devotees in temple architecture, symbolising non-violence and inner peace. The figure is encircled by iron tools, the broken parts of agricultural equipment. Tension forms between the figure and these mundane objects: strikingly incongruous, the implements threaten violence.

The Tools exposes the lurking hostilities of the early 1990s with the rise in communalism and the advent of globalisation. In House of heavens (1996), on display nearby, similar themes recur. While the human figure is absent, the effects of human action are palpable. A house and an egg rest against each other, intimating the home as a space for solace, refuge and the continuity of life. However, this ideal is destabilised by the iron sword upon which the house precariously rests, signifying the disruptions caused by rising social tensions and their intrusion into people's lives.

The glimpse of truth in one’s work is more important for me than whether you use colour well or other such technical virtuosities. Truth and ... a certain kind of confession.

Bhupen Khakhar

X

Within the changing cultural order, landscapes in works by Sudhir Patwardhan, Nilima Sheikh, Gulammohammed Sheikh and Bhupen Khakhar became spaces for reflection and change, with multiple and intractable negotiations embedded in their depictions. They offer not only a view of, but also a point of view on, both individual and collective lived experiences. At times they operate in a personal register, the landscapes aligning with intimacy, desires and dreams amongst more quotidian occurrences.

They reveal fluid moments between the interior and the exterior, between the visible and the mysterious, where temporalities are extended and even suspended, and boundaries blur between the making of art and the living of life. Affecting contemplations on the repercussions of state actions on the domestic realm, Arpita Singh's paintings and Vivan Sundaram's and N. N. Rimzon's installations further capture the tenuous line separating an ever-shifting landscape and the sanctum of home. They consider whether the home can remain a refuge, immune from the surrounding disturbances, the landscapes in motion. Collectively, however, these works demonstrate that life must continue despite and within these contested terrains.

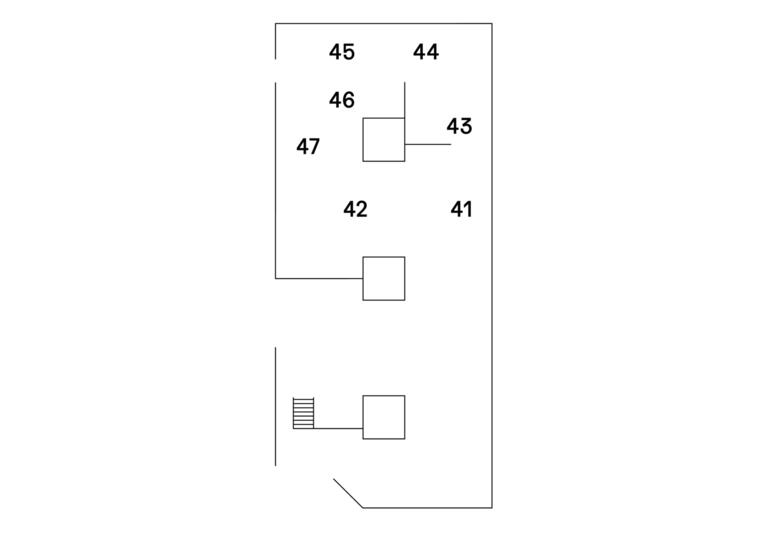

41 Gulammohammed Sheikh

How Can You Sleep Tonight?, 1994-95

Oil on canvas

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Moonlight glow illuminates richly coloured silhouettes in this work. Here, Gulammohammed Sheikh explores the relationship of the individual body to its surroundings and reckons with the political through painting.

Imagined creatures, multi-armed bodies, cloaked wanderers, archers, gunmen and pleading figures allude to the fraught reality of the anti-Muslim riots that followed the Babri mosque's demolition in 1992. At the bottom of the canvas, a couple lie awake and restless in bed. The title, taken from a Hindi poem by Suryakant Tripathi "Nirala" (1899-1961), asks a rhetorical question which implicates all.

Painted over two years after Sheikh had retired from teaching, this kaleidoscopic landscape demonstrates the artist's interest in Persian, Mughal, Indian miniature and pre-Renaissance painting traditions. Through lush colours and lines which swell and taper, he captures everyday life in small towns confronted with social change.

42 Nilima Sheikh

Shamiana, 1996

Hanging scrolls of casein tempera on canvas, canopy of synthetic polymer paint on canvas, steel frame Purchased 1996. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

Below a canopy painted in acrylic, the double-sided painted scrolls, or "kanats" (side screens), of this work centre on the journeys taken by women for devotion, love and celebration in the face of hardship. This nomadic theme is echoed in the installation's form as a "shamiana", a temporary shelter or gathering place often used as a marriage tent.

Nilima Sheikh began designing sets for the feminist theatre troupe Vivadi in 1989. This influenced her painting, and she experimented with ideas of scale and new ways of engaging with viewers. Shamiana allows its audience to move around and within the installation. From tender domesticity in Before Nightfall to the tragedy of When Champa Grew Up and then to a more hopeful paradigm in Shamiana, Sheikh invokes mythology and other vernacular literary traditions of the Indian subcontinent to explore human conditions of celebrating, mourning, protesting and offering shelter.

43 Sheela Gowda (b. 1957)

Untitled (cow dung), 1992/2002

Cow dung, pastel, ink on paper on board

Collection of the artist

Untitled, 1992

Cow dung, kumkum, textile, wood, pastel on paper and jute

Collection of the artist

Untitled, 1992

Cow dung, charcoal, pigment on paper and jute

Collection of the artist

Untitled, 1992

Cow dung, charcoal, pigment, wood on paper and jute

Collection of the artist

Mortar Line, 1996

Cow dung, pigment (kumkum)

Collection of the artist

In the early 1990s, perturbed by the rise in India of majoritarian politics and communal violence, Sheela Gowda, who had trained as a figurative painter, felt the need to explore other materials to make a more "potent response". She began to experiment with cow dung as it held a crucial resonance for her in the Indian cultural context.

Regarded as sacred in Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, the cow is also a symbol of non violence. In rural India, the preparation and handling of cow dung is usually done by women. It is utilised as fertiliser, insect repellent, cooking fuel and building material, for purifying the home and in the incense burned in temples.

Gowda first tested cow dung as a pigment, investigating its textural properties in a series of works on paper. These explorations then led her to sculpt with the material, preserving the cow dung with neem oil, fashioning it by hand into shapes from her local context - spheres, bricks, balls. This resulted in a series of installations, two of which are on view here.

Untitled (Cow Dung) (1992/2002) consists of 900 cow-dung patties and 25 bricks. Each of the pats carries an imprint of Gowda's hand from the flattening of the dung balls against a wall. The stacks of pats and bricks aim to highlight the material's numerous purposes beyond the ritualistic, and its connection to women's labour.

Mortar Line (1996) is a curved double line of cow-dung bricks. The cavity between the bricks is filled with kumkum, an auspicious red pigment. Viewed from a distance, the central chasm suggests a deep and bloody gash, while the title alludes to warfare.

By re-appropriating cow dung in these works and employing an abstract language, Gowda has harnessed readings connected to the material's cultural specificity, particularly its instrumentalisation for political ends in India, while still leaving room for other interpretations.

44 Sheela Gowda

Untitled, 1997/2007

Thread, pigment, needles Edition 1/3

Private collection

Alongside her explorations with cow dung, Sheela Gowda employed a range of everyday materials in her installations through the 1990s. Untitled (1997/2007), made for the show ‘Telling Tales - of Self, of Nation, of Art' at Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, is her first fully realised installation in which needle and thread are used. For this work, Gowda strung individual needles with threads varying in length from 40 to 133 centimetres. This labour-intensive process was very important for Gowda, who would reject a ball of thread if she encountered a single knot because "the process of threading empowers every inch" of the thread. She then anointed the threads with kumkum paste, and bound them together to form ropes, with a menacing head of needles at the end of each length.

Untitled comprises of eight such lengths of rope, which allow Gowda to configure and arrange them site-specifically. They travel viscerally along the wall and snake across the floor, intimating a transmuting body, an umbilical cord, intestines, trails of blood. Gowda has described the work as possessing "a very insidious sort of violence ... the needles hang at the end almost passively but they have the potential for hurting."

45 Bhupen Khakhar

Ghost City Night, 1991

Oil on canvas

Kanwaldeep and Devinder Sahney

Green Landscape, 1995

Oil on canvas

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

Pink City, 1991

Oil on canvas

Usha and Rina Mirchandani

Green Landscape, Pink City and Ghost City Night are a trio of paintings which share a similar compositional strategy - a large expanse of colour at the centre with loose renderings of villages and groups of romping men organised towards the edge. Here, Bhupen Khakhar's gestures are freer and bolder than in works such as Two Men in Benares and In a Boat, seen earlier. In Sudhir Patwardhan's opinion, this shift in aesthetic could only partially be attributed to problems with eyesight as Khakhar was consciously changing his mode of painting; the looseness of his strokes was intentional. The figures in these "messier" paintings are engrossed in all sorts of sexual encounters - kissing, fellatio, anal sex, voyeurism - and are not clearly defined. Importantly, they start to merge with the landscape.

It is a completely polymorphous universe with a clear sense of abandon, but also touched by uneasiness and illicitness. With these forceful works, Khakhar sought to confront the marginal place accorded to the queer community in India. Concurrently, he created images of reclamation, representing the rightfully inextricable place of their desire within a social-national landscape.

46 N. N. Rimzon

House of heavens, 1995

Resin, fibreglass, aluminium, marble dust

Purchased 1996. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation. Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art.

47 Sudhir Patwardhan

Memory: Double Page, 1989

Oil on canvas (diptych)

The Alkazi Collection of Art, New Delhi, India

Memory: Double Page is a panoramic diptych of an open landscape, soaked in the colours of the afternoon, and dotted with trees and low-lying houses. The work builds on Sudhir Patwardhan's practice, demonstrated earlier in the paintings Town and Overbridge, of combining multiple viewpoints to create a composite image which relays the experience of wandering through a locale.

The landscape depicted here, based on his childhood home, exists within the artist's memory, and he refers to the work as a "conceptual map" that recalls the locations of specific places in relation to one another. The result is a palimpsest of past and present versions of the same place. Interrupting the landscape are remembered fragments of buildings, a trellis, a linoleum floor, and roads which lead nowhere. Though his work's "realism" is often cited, here Patwardhan seems to suggest that the real lies somewhere between an actual place and our experience of it.

Look around where you are living?

C. K. Rajan

XI

Confronted by a fiscal crisis, the Congress Party-led government introduced a series of reforms in July 1991 that fundamentally altered the character and structure of India's economy. State regulations and controls were reduced to make the economy more market-driven and internationally competitive. As a result of this "liberalisation", India's GDP grew through the 1990s at an average of 6.6 per cent, almost double the rate before the reforms were initiated. However, the effects of a free market and whole-scale privatisation - mineral exploitation and indiscriminate industrialisation, among them - would prove massively disruptive, leading to wealth concentrated within a small group of corporations and elites, and the creation of a new middle class, while simultaneously dispossessing millions of other Indian citizens. The glaring inequities and exclusionism in an India that was promoted as "shining" would concern several artists, their works critiquing consumerism and the emerging paradoxes in the cultural domain.

48 Jitish Kallat (b. 1974)

Evidence from the Evaporite (He Followed the Sun and Died), 1997

Mixed media on canvas

Collection: Abhay Maskara, India

Jitish Kallat's Evidence from the Evaporite (He Followed the Sun and Died) is a mixed-media canvas in which the central image features a human body partially obscured by a water tank and surrounded by drawings of seemingly agitated men trapped in cylindrical containers. The background is of a "peeling billboard", the mottled surface provided by scraped-away layers of paint. Also included are found representations of famous landmarks of Bombay (Mumbai), images of the artist himself from different angles in the upper edge of the canvas, photographic negatives, a braided rope, and ants drawn towards rippling clocks.

Shown in Kallat's first solo exhibition, this work presents the changes in Bombay following the inter-communal riots of 1992-93, the individual experiences of living through such times, and the ensuing formation of ghettoes. Kallat dwells on the relationship between the self and the outside world, rendering decay at once alien and familiar, while also referring to the growing market in 1990s India for media technology and image production.

49 C. K. Rajan (b. 1960)

Mild Terrors II, 1991-96

Collages on paper

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art

Using only scissors and glue, C. K. Rajan composed the Mild Terrors II series by pasting imagery from discarded popular magazines and dailies onto blank sheets of A4 paper. An erstwhile member of the Indian Radical Painters' and Sculptors’ Association, Rajan began work on these collages in 1991, the year India liberalised its economy to allow foreign investment.

Made quickly and intuitively, the perspective of these small-scale collages is purposefully disorienting. They are replete with rescaled objects and discordant visual mash-ups. Rajan cannily juxtaposed outsized human torsos and limbs (often female) with consumer goods, and inserted them into urban or rural settings to create surreal scenes. They convey the "mild terrors" that lurked behind India's rapid entry into a global free-market system - the unreported uneven economic development, the social disparities, the displacements. It was a strangely transforming landscape, somewhere between pre modern, modern and post-modern, captured strikingly in these unsettling collages.

50 Jangarh Singh Shyam

Ped, Chidiya aur Hawaijahaz, 1996

Acrylic on canvas

Collection Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), Bengaluru

51 Anita Dube (b. 1958)

Desert Queen, 1996

Mixed media (velvet, plastic, foam, wood, metal, rope, thread)

Private collection

Intimations of Mortality, 1997

Enamelled votive eyes

Artist's Proof

Courtesy of the artist

Anita Dube created Desert Queen while attending a workshop near Africa's Namib desert. Made from sequinned dark blue velvet, the work recalls both a star-studded desert sky and a hide strung up after slaughter. Dube has commented that it could be "a woman, or an animal, or a mashak or wine sack". Hinting at violence, this work initiated Dube's practice of working with fabrics and fragile, found materials.

Intimations of Mortality, made the year after, consists of enamel-and-copper eyes arranged in the corner of a ceiling. The eyes, a cottage industry in Rajasthan, are used to animate statues of Hindu deities. Normally objects of ritual worship, here they become eerie, resembling pubic hair, a swarm of insects, or multiplying cells. In 1996, Dube's father was diagnosed with cancer. Her personal experiences of sickness and loss seemed to be mirrored in the violence and unrest in the nation. For the artist, the eyes stand in for people and speak to "large migrations in history". In its reference to forced displacements and disease, Intimations of Mortality is a metaphor for the threat presented by communalism.

As an art historian and critic, Dube was the only one of the Radical Group who was not from Kerala and its only woman member. When the group disbanded, she turned to making art.

52 Navjot Altaf

Bombay That Is That Is Not, 1995

Mixed-media installation

Collection of the artist

Bombay That is That is Not is a dynamic work that consists of a heap of empty photo frames as well as framed images of Bollywood celebrities, iconic artworks and artists. The work's configuration changes each time it is displayed.

Navjot moved to Bombay (Mumbai) in 1967 to study at the Sir J. J. School of Art, and was struck by "the vertical thrust of its multistorey buildings versus the horizontal sprawl of shanties at the ground level". The installation, which sprawls across the floor, addresses the glittering triumph of Indian cinema and glaring social disparity amid beguiling modernisation. Another component of the installation, now missing, confronted the intense intercommunal riots in Bombay following the demolition of the Babri mosque in Ayodhya. The floor-based installation also recalls peaceful protest actions, such as causing obstructions by lying across a path. When displayed initially, visitors could acquire any of the empty photo frames for a nominal price, a comment on the accessibility of art for all.

In our part of the world, the propaganda is that nuclear power is a deterrent, which sounds so paradoxical. We didn’t have a disaster, but we could have. This is a powerful potential that we have to combat in every sphere if we believe in humaneness.

Nalini Malani

XII

From 11 to 13 May 1998, India successfully conducted five underground nuclear tests in Pokhran, the site in the Rajasthan desert of the country's first nuclear test in 1974. The main objective was to confirm India's ability to build fission and thermonuclear weapons, as well as to assert the country's place in a new global order. The then prime minister, Atal Behari Vajpayee of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), cited a "deteriorating security environment" and, while alluding to China's nuclear capabilities, reiterated India's commitment to nuclear disarmament. India's nuclear capability was positioned by the nationalist government as a symbol of pride and immense scientific achievement, and, though met with nationwide euphoria according to most reports, it also faced protests from within the country. As Arundhati Roy states in her searing text The End of Imagination, "The nuclear bomb and the demolition of the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya are both of the same political process. They are both hideous by products of a nation's search for herself, of India's efforts to forge a national identity." The 1998 tests mark the furthest distance the country has travelled from the ideals of non-violence, which once had been the bedrock of its fight for independence from colonial rule.

53 Nalini Malani

Remembering Toba Tek Singh, 1998

Multi-channel video play, 4 projectors, 12 monitors, sound

Collection Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi

This video triptych was made in response to the 1998 underground nuclear tests in India, which were followed by similar tests in neighbouring Pakistan. It consists of a large central projection comprising archival material, and a single-cell animation drawing by the artist which depicts India on the left screen and Pakistan on the right, each with a silent female actor facing the other. Failing to fold a sari, they are preoccupied with the threat of the destruction that would unfold with the detonation of nuclear weapons, which carry intimations of horror, hegemony and machismo.

The video installation builds on Toba Tek Singh, a short story by Pakistani author and playwright Saadat Hasan Manto about forced displacement during the partitioning of the subcontinent in 1947. Nalini Malani was born in Karachi in undivided India. A few months after Partition, her family was forced to find refuge in Calcutta (Kolkata) before moving to Bombay (Mumbai).