Children's Games

Individual Children’s Games texts written by Lorna Scott Fox.

For the past two decades Alÿs has travelled to over 15 countries around the world to film children’s games – from ‘musical chairs’ in Mexico to 'leapfrog' in Iraq, 'jump rope' in Hong Kong and '1, 2, 3, Freeze!' in London. Staged in dialogue with an expansive selection of paintings, this immersive multi-screen installation presents the most comprehensive survey of the Children’s Games to date. Recording the universality and ingenuity of play, the series foregrounds social interactions which are in decline due to rapid urbanisation, the erosion of communities and the prevalence of digital entertainment.

Each film records lived experiences of play in different contexts and environments around the world, including Nepal, Belgium, Morocco, and Cuba. The artist often travels to games’ locations by invitation, responding to specific contexts such as the war in Afghanistan for dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel, Germany (2012) or extractive processes and environmental issues for the 7th edition of the Lubumbashi Biennale, Democratic Republic of the Congo (2022). In London, three local schools have participated in new films connecting the immediate Barbican community with the global constellation of voices documented in the Children’s Games.

All films from the Children’s Games series are public domain and can be watched and downloaded for free at francisalys.com.

Kujunkuluka

Many of us played this as kids, spinning on the spot until collapsing. In a group there’s a competitive element, each tries to be the last one still upright; but it’s only, always, about inner sensation. A crazy, soaring dizziness, a drugless altered state, glimpsed in the unseeing inwardness of some eyes that remain half-open. Arms outstretch like wings, amplifying and balancing the whirl of abandon. To the soft beat of unconsciously synchronised steps, the camera moves down to capture long shadows, like images of the disembodiment being felt: ghostly rotations among the sand stones bare feet don’t feel.

Children’s Game #36: Kujunkuluka, Tabacongo, D.R. Congo, 2022; 5:24 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux, Félix Blume, Kajila Ntambu, Douglas Masamuna and Picha Collective.

Imbu

Though mosquitoes have almost as many sensory auditory cells as we do, their hearing is for the sole purpose of finding a mate. Individual males (more wingbeats per second, higher frequency) and females (slower, lower) adjust their flight tones until a pleasing harmony is achieved. These boys have found a pitch irresistible to one sex – hopefully females, for malaria is growing in the D.R.C., and only pregnant females bite. Eros and Thanatos for the mosquitoes; for the boys, a small but satisfying cull of the horrible hordes.

Children’s Game #30: Imbu, Tabacongo, D.R. Congo, 2021; 4:58 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, Félix Blume and Picha Collective.

Appelsindans

Each couple tries to save an orange from gravity. When it falls, the pair is eliminated. This exercise in collaboration involves intimacy: faces are only an orange apart. It involves embraces, though not loving so much as keeping the partner in tension. Pacifying their natural energy with an eerie, giggly humming, the children shuffle like old marrieds at a tea dance, united and separated by a scandalous orange globe. Eyes sockets and cheekbones prove useless against roundness; even the winning couple’s triumph is short-lived.

Children’s Game #34: Appelsindans, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; 4:06 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, and Copenhagen Contemporary.

1, 2, 3, Freeze!

Grandma’s Footsteps in Britain, Red light, green light in North America, Thunder, weather, lightning in Austria, One, two, three, ciggy forty-three in Argentina, Frozen in Mexico, Statues in Greece – all refer to a game of stealth and balance popular around the world. While some versions rely on turning around at unpredictable intervals, these London kids play it with the regularly timed cry of 'One, two, three, freeze!'. The caller takes her time assessing everyone’s immobility, which ensures further wobbles. But she can only expel the most unstable, and the forwards progress won’t be stopped.

Children’s Game #45: 1, 2, 3, Freeze!, London, United Kingdom, 2024; 6:00 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, Félix Blume, Eduardo Puhl, St Luke’s CE Primary School and Barbican.

Ricochets

The bay is peaceful, framed by low hills in the distance. Three boys stand thigh-deep in the brown water, trousers rolled up. The biggest, on the left, is proficient in the art of stone-skimming: sending flat pebbles spinning over the water in such a way that they bounce off the surface as many times as possible before sinking. The middle boy feeds him stones from a stockpile inside his t-shirt, while the smallest looks on laughing. The skimmer throws quickly, intently, without thinking, without assessing his stone. Some stones sink at the second bounce; some skip a long way. It’s all the same to him, he must keep throwing.

Children’s Game #2: Ricochets, Tangier, Morocco, 2007; 4:43 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega and Julien Devaux.

Chivichanas

Cuban children have always built chivichanas for racing, using any wood to hand and ball bearings for wheels. During the hardship of the early 1990s, rural communities realised the potential of the toy and adapted it for personal and cargo transport, but in the streets of Havana it’s all about speed. Health and safety be damned, as up to five kids pile on and clatter downhill and around sharp corners at breakneck speed, steering the front wheel with an ingenious tiller. The film is a thunderous sound piece, too, with exhilarating moments of full immersion.

Children’s Game #40: Chivichanas, La Habana, Cuba, 2023; 4:43 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

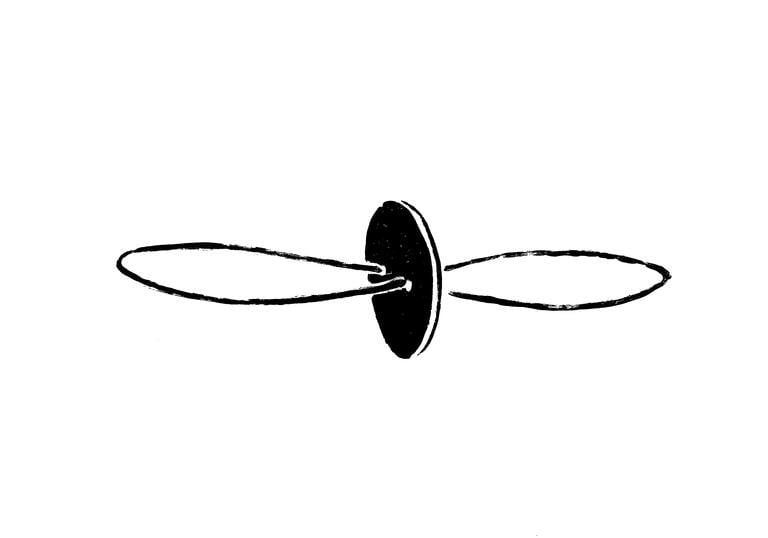

Chapitas

Ordinary bottle tops, once flattened, threaded and tensed for spinning, become as sharp as gladiator swords. It’s edge against thrumming edge as the jousters try to slice their opponent’s string by means of feints, angles, and jabs. The players fight in such close proximity that the emotion of each move is magnified in their faces, as if to compensate for the necessary restraint of thrusts and parries – take that, oh no, how about this, oops close one… gotcha!

Children’s Game #41: Chapitas, La Habana, Cuba, 2023; 3:53 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

Conkers

First recorded in the Isle of Wight in 1848, conkers was commonly played in the UK until it was banned from most schools in the early 2000s. Players alternate after three goes at exploding the opponent’s horse chestnut with their own. Points are assigned not to the handler but to the individual conker, as if it were a talented champion, like a racehorse; high scorers are often taken home and cared for. From the player, unerring aim rather than force is expected – we feel the frustration every time the target swings mockingly away. The fun part is when both strings get entangled, and the first player to shout 'snag!' wins an extra turn.

Children’s Game #46: Conkers, London, United Kingdom, 2024; 3:08 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Mariano Franco, Eduardo Puhl, Félix Blume.

Kluddermor

Children getting into a frightful mess that only parents could sort out: this familiar scenario plays out subversively, for the rescuing 'Mother' is just a child. A circle turns into a knot as the kids entangle themselves, still clutching, ever more twistedly, the same hands. Once paralyzed, the group cries chorally for 'Mother' and she appears. With remarkable engineering flair, ‘Mother’ figures out how to unknot the knot without breaking the links of hands, shoving arms over heads and directing legs under and over. Suddenly, like a disentangled string of Christmas lights, the chain becomes circular again.

Children’s Game #35: Kluddermor, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; 4:56 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, and Copenhagen Contemporary.

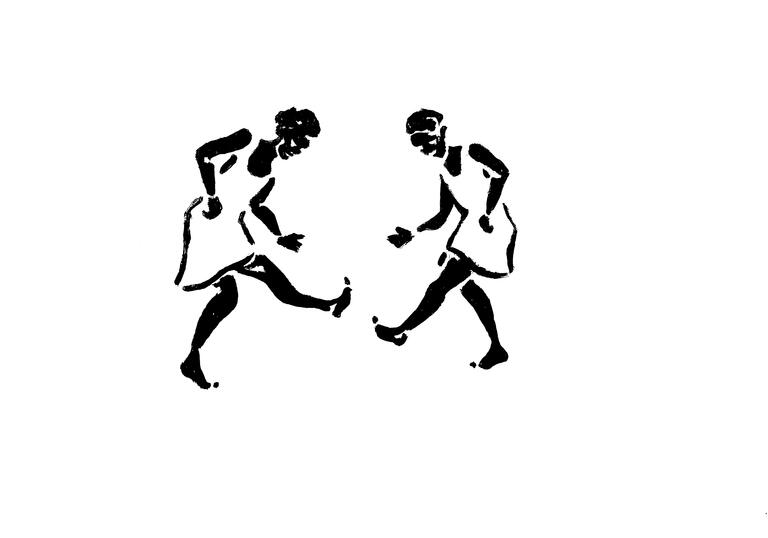

Nzango

Born in the recent past in school playgrounds and now a national sport, Nzango is a female-only game. The aim is to imitate, or more mysteriously, anticipate, the leg movements of the facing player. The pace is set by both teams singing and clapping in unison, faster and faster. Local variants thrive, ignoring the official rules. This, the girls’ own invention, involves 'minus' and 'times' signs, the first a mirror image – A’s right leg, B’s left leg – the second a crossed diagonal. And yet all the outsider perceives is a series of lightning confrontations, as pairs, then other formations, hop and kick ecstatically, advance and retreat according to an inapprehensible logic, telepathically improvised, perhaps. What geometry rules the final blur of legs?

Children’s Game #28: Nzango, Tabacongo, D.R. Congo, 2021; 5:41 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, Félix Blume and Picha Collective.

Jump Rope

Stark though it is, the roof terrace with its low ochre-red wall and washed turquoise abstract seems the nearest thing to a garden among the forbidding cliffs of mass housing that rear up all around. Like bold tendrils of organic life, three young girls appear with jump ropes and show off some individual fancy licks, before switching to a stately coordination mode. Their bright white ropes make squiggles in the air like waved sparklers at night, while wrists and feet maintain a rock-steady beat. The joy of skilled movement, of pure synchrony, illuminates their faces.

Children’s Game #22: Jump Rope, Hong Kong, 2020; 5:28 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, Félix Blume and Tai Kwun Contemporary.

Sandcastles

The castle must be positioned just far enough from the sea to be completed before the tide reaches it. As the moat is dug by busy spades, the vacated sand forms a growing pile in the middle. Sea water starts to rise into the moat from below. As the waves break gently, closer and closer, the children dig faster to fortify the outer rampart with sodden sand. Even as the defences are being flooded, they work on shaping and firming the castle with hands and feet. The tide soon overwhelms the mini world and smooths the whole thing flat, leaving the children standing ankle-deep in ebb and flow.

Children’s Game #6: Sandcastles, Knokke-Le-Zoute, Belgium, 2009; 6:04 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux, Cristian Manzutto, and Félix Blume.

Papalote

A 10-year-old boy in a pink salwar kameez stands near a dune coloured wall under a powder-blue sky. He frowns and gesticulates, conversing in stops and starts with the heavens or at least with the gusting wind because you don’t see his kite at first, and the string is so fine you can’t see that either. What you see is a body interacting with unknown forces, pulling to the left, the right, up, down, quick, over to the left again, and so on. Here is not only the body of the boy but the body of the world in deft mutual mimesis, amounting to 'the mastery of non-mastery' which is the greatest game of all: a guide, a goal, a strategy – all in one – for dealing with man’s domination of nature (including human nature). Afghan kite fighters often attach small blades to their kite strings, or coat them with ground glass and glue, the better to down their opponents’. Under the Taliban, kiteflying was banned.

Children’s Game #10: Papalote, Balkh, Afghanistan, 2011; 4:13 min. In collaboration with Elena Pardo, Félix Blume, and Ajmal Maiwandi.

Stick and Wheels

On a wide, gravelly mountain road, earth-coloured dwellings in the background, small boys scamper behind tyres of different thickness and circumference, beating them onwards with a stick. A donkey brays in sympathy. The thin, flexible tyres of bicycles are the hardest to keep upright, especially when performing turns (slowing and tilting the rubber hoop without loss of momentum) before racing back, sometimes in competition with another, cheered on by their companions, towards the starting line.

Children’s Game #7: Stick and Wheels, Bamiyan, Afghanistan, 2010; 5:22 min. In collaboration with Natalia Almada.

Parol

First we drive past harrowing scenes of missile and bullet damage, into an area that’s still intact. At a crossroads not far from the frontline, three boys in fatigues, with wooden guns, act out a grown-up duty: to uncover Russian spies. The drivers, both soldiers and civilians, are cheered by the children’s playful solidarity. Cars are flagged down, IDs requested, trunks inspected. A password is demanded: Palyanitsya, the name of a traditional Ukrainian bread, and a word that Russians can’t pronounce right. As it happens, bread also is the universal symbol of life.

Children’s Game #39: Parol, Region of Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2023; 8:02 min. In collaboration with Hanna Tsyba, Olga Papash, Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

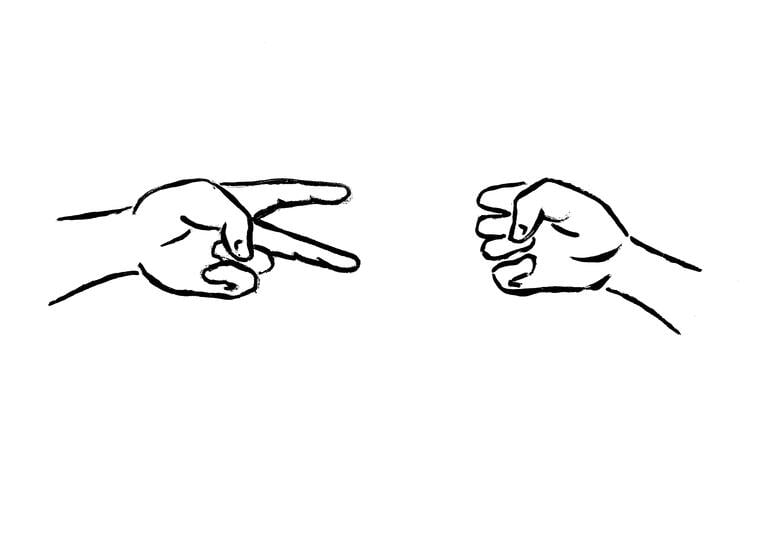

Piedra, Papel o Tijera

This ancient Chinese game is played between two people, who in unison say 'rock, paper, scissors' before 'throwing' one of the three figures at each other: closed fist or flat hand or two fingers in a V shape. Rock blunts scissors, scissors cut paper, paper enfolds rock. Each round is win, lose or – if both players choose the same 'tool' – draw. We see not hands but a shadow-play of hands against a pale background, as the two antagonists display the tremendous skill that kids alone can muster in what seems impossibly fast motion. 'Conceptual art,' you say, the kind you could watch for hours, the hands as synecdoche not of the body but of two bodies in a rhythmic frenzy of elegant interaction and dissolution.

Children’s Game #14: Piedra, papel o tijera, Mexico City, Mexico, 2013; 2:51 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

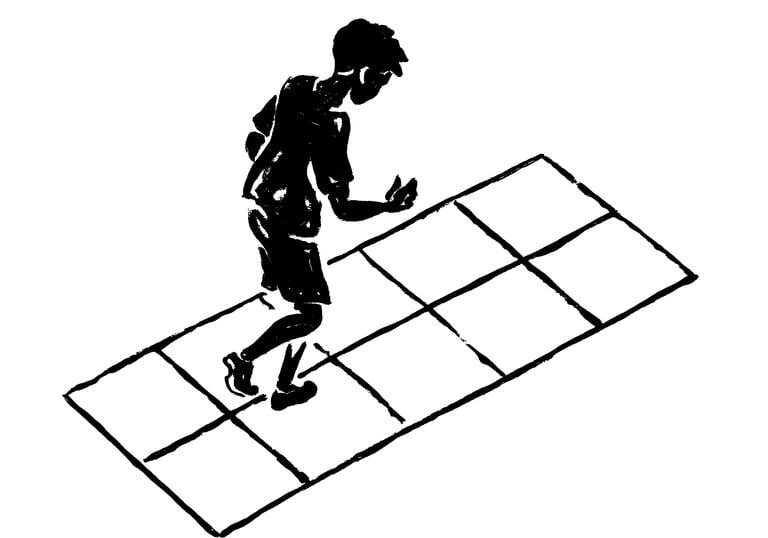

Hopscotch

Outside a stark tent city, this version of the game involves a grid of squares, two across by six long, marked by lines gouged into the arid ground. The player tosses a stone into the grid and starts hopping up one side of it to where the stone lies, careful to land only once in each square or station. When the stone is reached it must be kicked or nudged back down the other side to the start line, still hopping on the same foot. The test is difficult, and few succeed. For as the closing subtitles tell us: 'In ancient cultures hopscotch symbolizes the progress of the soul from Earth to Heaven. The player hops between Worlds to escape Hell and reach Heaven, from which he will return to Earth reborn and redeemed.'

Children’s Game #16: Hopscotch, Sharya Refugee Camp, Iraq, 2016; 4:02 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux, Félix Blume and Ruya Foundation.

Contagio

An update of tag, the scariest of kids’ games. Instead of the touched person being 'frozen,' they are contaminated and activated as viral transmitters. Boys and girls sport face coverings, any colour but red, the colour of contagion, worn by the first It. On catching someone the tagger shouts 'Contagio!' and the victim echoes, 'Contagiado!' Infected! while changing into a red mask (already glimpsed peeping from pockets, in fatalistic preparedness) to become It. The last child standing cries 'Survivor!' In August 2021, 43 Mexican minors officially died of Covid; the true figure would be much higher. Tag was always about the menace of other people, but Contagio is brutally literal.

Children’s Game #25: Contagio, Malinalco, Mexico, 2021; 5:30 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux, Elena Pardo, Félix Blume and Imaginalco.

Ellsakat

Neither indoors nor out, but on the doorstep, where you might play a quick game while waiting for someone. Girl and boy pile up candy wrappers, face down; elsewhere, for the game is widespread, it could be cards, tokens, any flimsy object with a front and a back. A lightning round of scissors-paper-rock decides who slaps first. The aim is to make the colourful, 'right' sides appear, and these wrappers can be claimed, yet are soon back in play. The siblings have identical profiles, and sometimes positions, like one person playing in a mirror. When the door opens and the someone appears, they rush off into their day.

Children’s Game #38: Ellsakat, Azilal, Morocco, 2023; 4:54 min. In collaboration with Ivan Boccara, Julien Devaux, and Félix Blume.

Rubi

With all the charm of flick soccer, Subbuteo, pinball, and other miniature passions, this is played on a small circle of stubby broken-off sticks like a frontier fort buried in the sand, enclosing two facing, immobile teams also made of little sticks. Resembling two giants crouched over cavernous goals, the competitors take quickfire turns thumbing a marble, careful not to touch anything else. The successful marble shoots in from the side or arcs with precision through the air. For a penalty, it is balanced on top of the defending palisade. Close-ups on fans, rapt faces and dusty feet, bare or in the moulded sandals that protect knees as often as feet. The ring of attention is bisected by a chicken scooting straight through people, the exact centre of the arena, people, and out, as if performing a dare.

Children’s Game #27: Rubi, Tabacongo, D.R. Congo, 2021; 6:17 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux, Félix Blume and Picha Collective.

Slakken

Snail racing is a game of unequal chances, especially when your snails are not trained champions, but randomly plucked off a wall; individual temperaments and moods count as in any sport. They are supposed to radiate out towards a circular finishing line, but one mollusc is stubbornly introverted, while another may be heartsick: its sponsor speculates that 'it needs love, it hasn’t eaten much.' Several think it’s more fun to climb over each other. Little girls’ nails echo the bright blobs of paint on shells. The children’s choral twittering resolves into 'Allez! Allez!' It’s a photo finish. Suddenly rain sheets down and the kids stampede, almost causing a tragedy. The racing colours wash off like smoke glowing in water.

Children’s Game #31: Slakken, Pajottenland, Belgium, 2021; 5:01 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

Knucklebones

Knucklebones, or jacks, has existed for more than 2000 years and was first played with the astralagus bones of a sheep. This version – played with stones by two girls seated on the landing of a concrete stairway, people’s legs and occasional monkeys passing by – is close to the Korean Gonggi, with no separate ball. The turn begins by throwing a stone in the air and performing certain actions with the four others before catching it again. Later all are tossed up and received, at least some, on the back of the same hand. Pick-ups are sometimes between splayed fingers. The film blurs the logic of any sequence, dwelling on the leaping, clattering stones, and the agility of dusty hands.

Children’s Game #18: Knucklebones, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2017; 6:08 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux, Félix Blume, and the Kathmandu International Art Festival.

Step on a Crack

A sprite in a blue pinafore, plimsolls, and white facemask flits through Hong Kong, enclosed in a quicksilver bubble of magic. Streets become the dull, slow backdrop to her vividness. Oblivious to storefronts and curious stares, seeing only the yellow lines and the cracks in the pavement, she snakes and two-steps around seams and lines without loss of élan, chanting spells that shade into vague sounds. 'Step on a line, break the devil’s spine, Step on a crack, break the devil’s back, Step in a ditch, your mother’s nose will itch, But if you step in between, everything will be keen!' By igniting her route with meaning, she briefly wrests public space from the commercial values this city lives by.

Children’s Game #23: Step on a Crack, Hong Kong, 2020; 4:57 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, Félix Blume and Tai Kwun Contemporary.

Schneespiele

The most basic sense of fun improvises on chance gifts of the environment. Snow-fun is too immediate to need rules, either. One game suggests another. First a chaotic battle sequence, with snowballers spied on from behind tree trunks, a little hill to be conquered; then everyone unites to slide down a bigger slope, in squealing collective release. Finally, a massive snowball that is implored to roll downhill. Snow, so protean and malleable, so resistant in bulk; so soon to vanish.

Children’s Game #33: Schneespiele, Engelberg, Switzerland, 2022; 5:26 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

Leapfrog

Leapfrog in English, saute-mouton in French, haasje over in Dutch, kabbadi in Hindi, bockspringen in German. Frogs, sheep, hares, dogs, and deer are all exuberant jumpers; Mexico provides an exception with the resigned, earthbound donkey of el burro. Rules vary around the world, but generally stage an idealistically reversible game of domination: everyone is both leaper and leaped, and the last become first. The players here are not all wearing their usual clothes, for these are screen tests for the film Sandlines, in which kids act out a century of Iraqi history. We glimpse, without knowing, Mr. English and Mr. French, Saddam Hussein, a Kurd, an Arab shepherd... The main contribution of such costumes is the challenge of keeping one’s hat on while being leapfrogged. Anarchy is always just a tumble away. One girl even tries to vault back up the line – a new variant that could catch on.

Children’s Game #20: Leapfrog, Nerkzlia, Iraq, 2018; 5:53 min. In collaboration with Ivan Boccara, Julien Devaux, Félix Blume and Ruya Foundation.

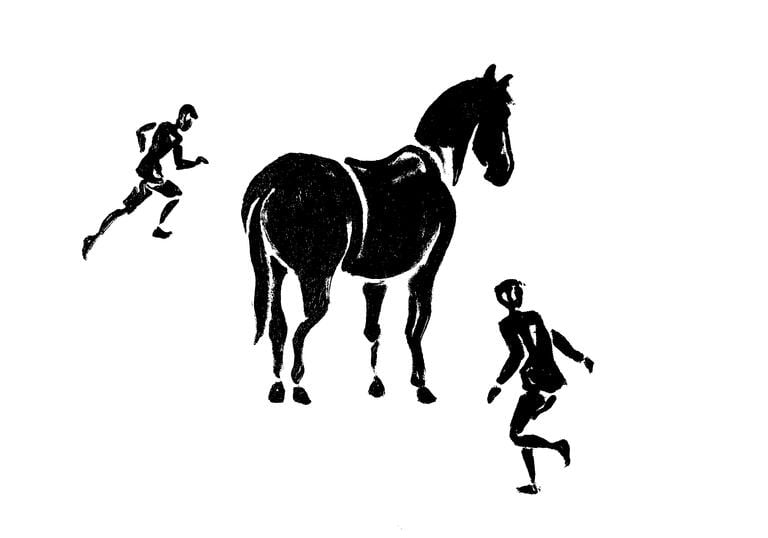

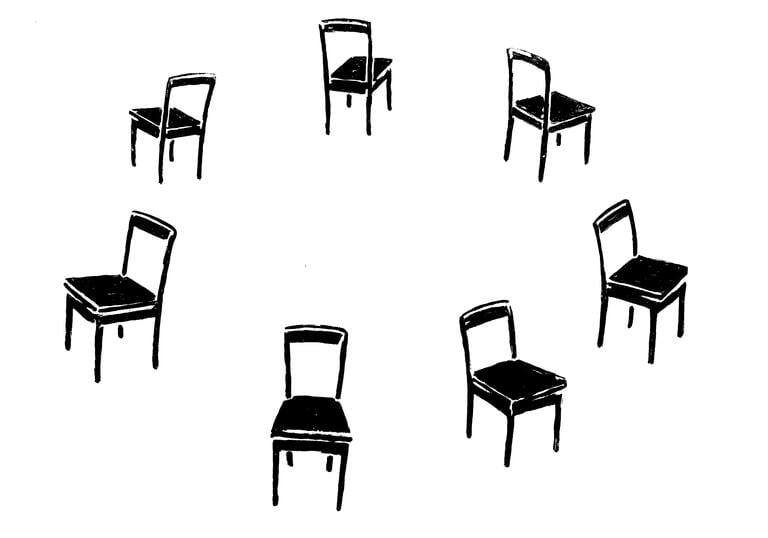

Musical Chairs

The game is filmed from above in a single take, emphasizing the inexorable process of subtraction. Six children place five chairs in a row, facing in alternate directions. When the music starts, the players skip one behind the other around the chairs. When the music stops, everyone scrambles to occupy the nearest chair and one person is left standing. The loser carries a chair away, stomping out of shot to the left. The music starts again, and so it goes on until the winner claims the last chair. Then there is only an empty space.

Children’s Game #12: Musical Chairs, Oaxaca, Mexico, 2012; 5:05 min. In collaboration with Elena Pardo and Félix Blume.

Espejos

Boys stampede through the shells of small geometric homes, fancy boxes falling to bits in a dry-grass wasteland like futuristic ruins. The players flatten themselves behind walls, peer cautiously with half an eye from glassless windows. Each boy holds a piece of broken mirror and aims at the enemy with the light refracted by the sun. They can’t resist making shooting noises, though these burning bullets are flashes from millions of miles away. Wandering dots of brilliance seek bodies out. Once a player is blinded by the light, he slumps and dies.

Children’s Game #15: Espejos, Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, 2013; 4:53 min. In collaboration with Alejandro Morales, Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

Haram Football

A street in golden evening light, lined with burnt-out cars and wrecked buildings. A dozen boys, between 8 and 16 years old, greet one another cheerfully. The East Bank of Mosul was liberated days ago; football is no longer haram, forbidden. The ball is lobbed into play. Except there is no ball. Re-enacting the trick they perfected under the rule of Islamic State, here is the beautiful game as mysterious dance: dribbles and dodges, leaps and headers, a display of fluid grace and unusual harmony: there’s no arguing over the whereabouts of the ball or whether it scored, was saved, or rolled into the bomb crater over there. Was football haram because it resembles a religion? This seems even truer where the ball is as invisible as any god and as real in its effects on human action. The ritual is interrupted by profane time, as a burst of gunfire scatters the players and the street is left holding its breath.

Children’s Game #19: Haram Football, Mosul, Iraq, 2017; 9:11 min. In collaboration with Julien Devaux, Félix Blume and Ruya Foundation.

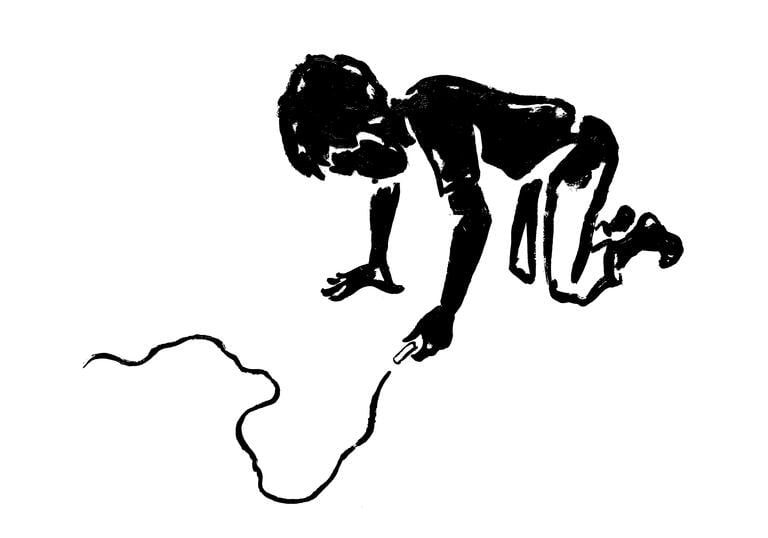

Chalk

Shot in black and white in homage to Helen Levitt, the pioneering photographer of children chalking the streets of Harlem in the late 1930s, this film records individual acts of creation by children from two schools local to the Barbican Centre in London, including students with physical and neurological diversities. Marco goes for horseshoe-shaped patterns, before expressing his self in a spontaneous spatter; Jean-Luc builds oneiric form upon form; Charlyn’s creatures emerge in clear, expansive lines. For Ayesha and James, the chalk is not just a drawing tool but also a curious object for fingers to explore, like they do with the texture of asphalt or the powderiness of their marks. Sensation and imagination imbue every scratch of white on black these children make.

Children’s Game #47: Chalk, London, United Kingdom, 2024; 15:17 min. In collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, Félix Blume, Eduardo Puhl, Prior Weston Primary School, Richard Cloudesley School and Barbican.

Paintings

Spanning three decades of the artist’s career, this group of small paintings is presented in dialogue with the Children’s Games film installation. Illuminated by sharp beams of light, each work is a window revealing a place in time that punctuates the dark cinematic playground of the Children’s Games. Alÿs’s distinctive signature as a painter is to use oil on canvas mounted on small, solid wood panels only slightly larger than postcards. Painted between 1990 and 2024, these intimate works are titled after the cities Alÿs travelled to, recording scenes witnessed by the artist in the public space. The eye is drawn to the figures – mostly children – at the heart of the canvases, portrayed both in groups and alone. Luscious landscapes and pared down urban compositions appear deceptively serene as world events unfold within these miniature scenes, often capturing the resilience of everyday life in zones of conflict or social unrest. 'What does it mean to make art while Nimrud and Palmyra are being destroyed?,' the artist writes. 'What could a Belgian artist based in Mexico say about the situation in Afghanistan?' Between 2010 and 2014, Alÿs travelled extensively in Afghanistan, witnessing the aftermath of Taliban rule, which had curtailed the simple freedoms of childhood. From the narco-violence in Mexico to the COVID-19 pandemic, the paintings are directly inspired by drawings and sketches from Alÿs’s notebooks, depicting the geopolitcal contexts of the places he has travelled to. The artist bears witness through his drawings and paintings; they are 'an attempt to coincide with the moment I am living,' he writes.

Veracruz, MX, 1990

Oil on canvas

16.1 × 22 × 1.5 cm

Havana, Cuba, 1994

Oil and encaustic on wood

10.5 × 14 × 1.6 cm

Manaus, Brazil, 1995

Oil on canvas

11.5 × 15 × 1.6 cm

Chiapas, Mexico, 1995

Oil on canvas

12.9 × 18 × 1.7 cm

Burma, June, 1997

Oil on canvas

10.1 × 15.1 × 1.6 cm

Shanghai, June, 1997

Oil on wood

11 × 16.5 × 1.6 cm

Shanghai, China, 1997

Oil on canvas

14.5 × 19 × 1.6 cm

Jerusalem, Feb, 2003

Oil on wood

13 × 18 × 1.6 cm

Yazd, Iran, 2006

Oil on wood

14 × 19 × 1.6 cm

Gibraltar, 2008

Oil on canvas

16 × 21 × 1.6 cm

Bamiyan, Afghanistan, 2010

Oil on canvas

12.5 × 17.5 × 1.6 cm

Untitled (Pierrot), 2010

Oil and collage on canvas

13 × 18.1 × 1.5 cm

Afghanistan, 2012

Oil on canvas and collage

13 × 18 × 1.6 cm

Kabul, Afghanistan, 2012

Oil on canvas

13 × 18 × 1.6 cm

Ciudad Juarez, MX, 2013

Oil on canvas

16 × 21 × 1.6 cm

Shariya Refugee Camp, Iraq, 2016

Oil on canvas

13.3 × 18.3 × 1.6 cm

Baghdad, 2016

Oil on canvas

13.1 × 18.1 × 1.6 cm

Mosul, Iraq, 2017

Oil on canvas

13 × 18 × 1.6 cm

Hamman-al-Alil, Iraq, 2018

Diptych. Top: Graphite on canvas Bottom: Oil on canvas

Each 14 × 18.5 × 1.6 cm

Coyoacan, Mexico, 2019

Oil on canvas

13 × 18 × 1.6 cm

Lubumbashi, D.R.Congo, 2021

Oil on canvas

10 × 15 × 1.6m

Haut-Katanga, D.R. Congo, 2021

Oil on canvas

17 × 21 × 1.6 cm

Montréal, Canada, 2023

Oil and graphite on canvas

12.3 × 17.8 × 1.6 cm

Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2023

Oil and encaustic on wood

14 × 18.8 × 1.6 cm

Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024

Oil on canvas

16 × 20.8 × 1.6 cm

Untitled, 2024

Oil and encaustic on canvas

21 × 16 × 1.6 cm

Siren was made during Alÿs’s time in the Kyiv and Kharkiv regions of Ukraine following the Russian military invasion that began on 24 February 2022. Filmed in May 2023 it captures the precarity and urgency of games in contexts of conflict and war, centring the resilience of children’s voices. The melody of the siren carries in it both a lament and a song of resistance. Looking straight into the camera, some children are resolute, determined, fierce, their voices resounding and harmonious; others hum and giggle while trying to sustain a note; still others take pauses and deep breaths. Polya, downcast, emits a short, trembling whine, then falters and runs offscreen. In the final shot, a white paper plane is cast off the roof of a building, plummeting through the air past charred buildings. As it drifts down it appears to transform from plane to white dove, landing soundlessly on the ground.

'Imitating sirens,' a subtitle tells us at the end, 'is part of the "Air Raid Alert" game played by Ukranian children today.' The game itself begins with children mimicking the sirens, after which they build a shelter with pillows and cardboard boxes. They then take their dolls and toys into hiding and cover the shelter with rubble, launching a counterattack of paper grenades until all enemies are destroyed.

Siren, Ukraine, May 2023; 5:36 min. In collaboration with Hanna Tsyba, Olga Papash, Eugene Moroz, Julien Devaux and Félix Blume.

Emerging from the many bodies, voices and faces captured in the Children’s Games, we are met with a pair of swinging feet. Drawn, then animated in black-and-white, they swing from some unknown place – a branch, a tree-house, a swing, the edge of a bed or the side of a pool – to the soundtrack of a crooning lullaby. Walking feet recur in Alÿs’s practice. His paseos or strolls have wandered the streets of urban capitals including Mexico City, São Paulo, Havana, Paris, Stockholm, while his interest in parades and processions has manifested in largescale performative gatherings like The Modern Procession (2002), in which replicas of the iconic works in MoMA’s collection were walked from Manhattan to its new building in Queens.

But these feet are not in procession or on their way; they are nowhere bound, subverting the bipedalism of adulthood by languidly swinging in place. They may be at play, winding down to sleep, or simply wasting time: here is a game with no rules, a simple, looping gesture, activating a wandering of the mind and signalling a different experience of time, a new mode of attention.

Untitled, 2024. In collaboration with Esteban Azuela and Diego Solano.

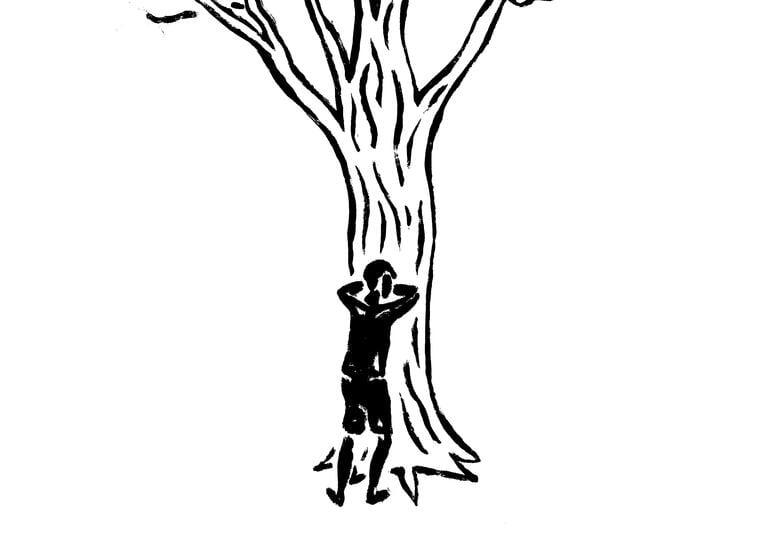

In contrast with the chorus of eyes in the painting greeting us downstairs, here is a boy turned away, covering his face against a tree trunk. What game is this? The others have dispersed, or perhaps lie hiding as the boy prepares for a game of Hide and Seek. The proliferation of players in the Children’s Games has given way to the single figure, an individual who might be one of many but appears before us starkly alone. The mysterious forest could be the realm of the artist’s childhood, one he recounts as made up of games often played on his own in the Flemish countryside. Unlike the small paintings dispersed through the lower gallery – windows into everyday scenes situated in time and place – we are transported to a nameless, timeless, dream-like setting. We find ourselves in an allegorical landscape or a forest of dreams, evoking the sparsely populated, metaphysical paintings by the surrealist Giorgio di Chirico, an influence on Alÿs’s painterly language. Or perhaps peering into the illustration of a fairy tale or fable: as Alÿs reminds us, “Just as the highly rational societies of the Renaissance felt the need to create Utopias, we of our times must create fables.” The boy might be a player counting to ten; with his gaze withheld – or turned inwards – he might also be a sentinel, oracle or seeker, prompting us to look with all our senses and conjure new fables.

Untitled (corner painting), 2024. Oil and encaustic on canvas, 21 × 16 × 2 cm.

Expanding Alÿs’s interest in play, this new series of animations, shown here for the first time, is in dialogue with the Children’s Games. In the latter, the body is contextualised in both space and time, engaged in plural and collective acts of play. Meanwhile in these hand games, the body has been fragmented and the hand isolated, prioritising a direct and intimate experience of quiet, tactile exchanges. The bright, colourful scenes of the Children’s Games films – referencing the vivid multitudes of Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s painting Children’s Games (1560), which Alÿs saw as a child in Belgium – have been replaced by soft, black-and-white line animations.

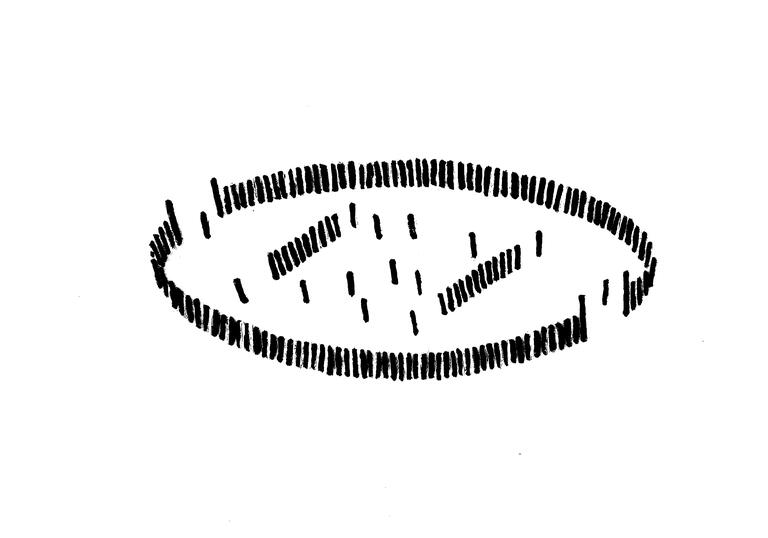

The haptic subject of the hand playing games is echoed by the manually laborious process of animation: each work is composed of hundreds of individual line drawings to achieve the hand in motion. In one room, hands walk. In another, they stack as though in a slower, pared-down version of the animation’s filmic counterpart, Children’s Games #21: Hand Stack (2019). Elsewhere, thumbs swivel and dodge in a game of thumb war, and make wolves, birds and rabbits in a game of shadow play. Echoing the display of previous animation works, this series is shown as a round projection: a vignette playfully mimicking the shape of the eye, while focusing attention on games led by the hand. The animations loop continuously, replaying a series of gestures that reveal a vocabulary of games premised on nothing more than the hand and its rhythms.

Thumb War, 2023–2024. In collaboration with Emilio Rivera.

Finger Walk, 2024; Manos Caminando, 2023.

Hand Stack, 2019–2024. In collaboration with Emilio Rivera.

Ombres Chinoises, 2024. In collaboration with Esteban Azuela and Diego Solano.

Playrooms

Two playrooms invite you to perform your own games within Alÿs’s universe of play. Developed by the Barbican team in dialogue with the artist’s long-time collaborator Rafael Ortega, these rooms deploy the key components of moving image: light, shadow and sound. Inspired by the hand shadows in Alÿs’s animation series of hand games, the first room encourages you to cast shadows and play with shapes and scale. In the second room, you are invited to find new paths in the space on low stools on wheels, and prompted to interpret performative actions read out by children. These playful instructions were conceived by 60 children, as part of a series of workshops in a year-long art and learning programme developed by the Barbican and led by Ortega and educator Lucy Pook with three local schools: Prior Weston Primary School, Richard Cloudesley School and St Luke’s CE Primary School. In these spaces you might make a bird with your hands, become a giant in the light, sing your favourite colour, or spin your way around the room: the rules of the game are in your hands.

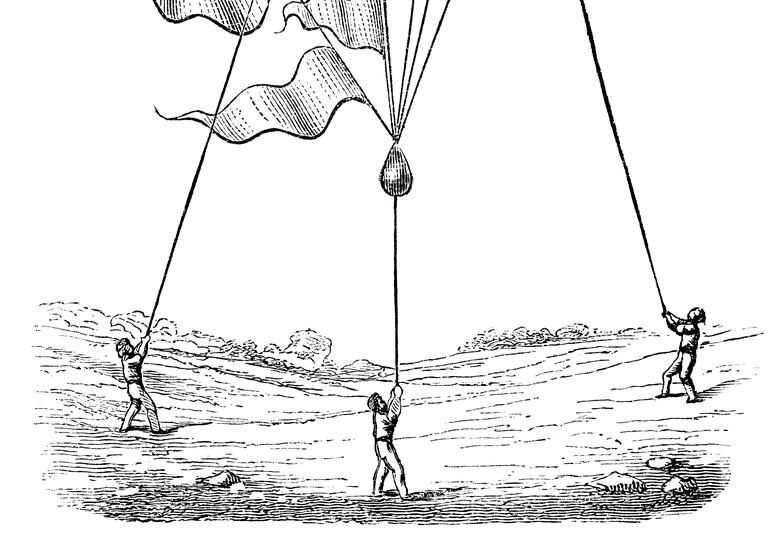

Stories of Games

A constellation of source material on children’s games loops around the banister of the upper gallery. The games in Alÿs’s Children’s Games series were the starting point for an expanded archive of play, made up of a transhistorical sequence of images reflecting the circulation and transnational influences that have shaped and transformed the structure and appeal of games across social and geographical contexts. Rather than attempt to chart an encyclopaedic, chronological survey, the images are organised in fluid groupings. These both demonstrate the diversity and vastness of depictions of games, and the fragmentary nature of archives in compiling, preserving and providing access to global stories of play. Spontaneous or rehearsed, collective or solitary, passed down through generations or imagined anew, the games represented in this selection transmit the vitality of a stone skipping on water, or of voices ricocheting off each other in an open space.

Explore

Catalogue

Available from the Barbican shop

The exhibition is accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue edited by Florence Ostende, published by Prestel, with graphic design by Mark El-khatib. It explores Alÿs’s influential works in dialogue with his critically acclaimed Children’s Games films (1999– present). Revealing new perspectives on his prolific career, a series of essays by Helena Chávez Mac Gregor, Carla Faesler, Cuauhtémoc Medina, Florence Ostende and Inês Geraldes Cardoso explore the artist’s studio practice and influences across art history, philosophy and literature.

Private View: Francis Alÿs

Watch on www.nowness.com

A short film made in partnership with NOWNESS explores Children’s Games and the new films commissioned by the Barbican and filmed in the City of London for Ricochets.

Activity Sheet

Free copies at the Gallery

Delve into this resource, made with children from three schools local to the Barbican – Richard Cloudesley, Prior Weston, and St Luke’s – to find out more about the artist, ideas and themes of the exhibition while engaging in playful activities as you explore the works on show.

Tristan Garcia: Keynote Lecture

Thu 27 Jun, 7pm – Frobisher Auditorium 2

A keynote lecture by celebrated philosopher and writer Tristan Garcia explores the multifaceted nature of childhood in art, philosophy and cultural history through the prism of children’s drawings. Recreations: Three Films on Children’s Play Thu 8 Aug, 6:30pm – Cinema 2 A trio of films captures glimpses of childhood: from 1970s Tehran in Abbas Kiarostami’s The Bread and the Alley; to a wintery, mid-1960s Amsterdam in Beppie by Dutch documentary filmmaker Johan van der Keuken; ending with Claire Simon’s Récréations, a portrait of her daughter through games in a 1990s Parisian schoolyard.

Curator Tours

Thu 4 Jul, 6:30pm by Curator Florence Ostende – Gallery

Thu 18 Jul, 6:30pm by Assistant Curator Inês Geraldes Cardoso – Gallery

Join a curatorial guided tour highlighting key works and introducing the themes of the exhibition.

Family Day

Sat 6 July, 11-2pm – Conservatory

Bring friends and family together to explore Alÿs’s works and ideas. Take part in a series of creative workshops for all ages and get making, crafting and playing! Includes free entry to the exhibition.

Our Street

1-23 August, 10am-6pm – The Curve

Step into Our Street, an imaginary neighbourhood full of games and activities. The whole family can join in with the fun: take part in workshops and street parties during the day before it becomes an evening zone for serious gamers on 8, 15 and 22 August.

Play Pack – Free copies (limited) at The Curve and online

Inspired by Alÿs and the idea that ‘play is everywhere’, this resource includes playful activities for the body and mind, to be enjoyed indoors and out. Made in collaboration with artists, community groups and designers, it celebrates diverse cultures and explores connections between generations through games.

School Workshops

2, 9 and 16 July – Art Gallery

Bring your class (Key Stage 2+) to experience this new exhibition exploring children’s games, and take part in a workshop, free of charge. Aimed at Primary and SEN/D groups, but all welcome. Places are limited. Email schools@ barbican.org.uk to book.

School Visits

Free entry to the exhibition for students up to Year 9. A discounted booking rate of £3 per student is available for older students in formal education groups of 10 or more, up to age 19. Book for a school or college group via [email protected]. uk or our online form.

Pay What You Can

Every Monday (10am–12pm) and Thursday (5–8pm)

Select the ticket price you can pay and enjoy the exhibition.

Francis Alÿs: Ricochets

27 June — 1 September 2024

Curator

Florence Ostende

Assistant Curator

Inês Geraldes Cardoso

Exhibition Organiser

Rita Duarte

Artistic Coordination

Rafael Ortega

Production Manager

Maarten van den Bos

Creative Collaboration

Josie Dick and Carmen Okome

Graphic Design

Mark El-khatib

Children’s Games texts

Lorna Scott Fox

Print

Impress Print

The exhibition is curated by Barbican, London and organised with Serralves Foundation – Museum of Contemporary Art, Porto.

Generously supported by the John S Cohen Foundation, the Delegation of Flanders (Embassy of Belgium) and the Company of Arts Scholars Charitable Trust.

All works are courtesy of the artist. Unless otherwise stated, all images are © Francis Alÿs.

Join as a Member today

Visit all our exhibitions for free, as many times as you like. Plus, get exclusive benefits across the Barbican. Sign up today and save the price of your exhibition ticket.