It was within the deep cuts of her parents’ record collection that a young Beatie Wolfe first began to consider the album as an art form worthy of the unrivalled prestige she has shown it over the years. ‘I just spent all my time going through these records and imagining what that world was about,’ recalls Wolfe. ‘From that age, which was seven or eight, I was imagining “what worlds I could create for my albums, what would they look like, what would they feel like?”’ Those worlds can be found in Wolfe’s stripped back acoustic indie and hushed, dulcet takes on love and loss, drawing inspiration from lauded singer-songwriters like Leonard Cohen and Elliott Smith. Rather than simply recreate the past, Wolfe sought out a new way to celebrate music, taking the best of the old and new to create something far more imaginative.

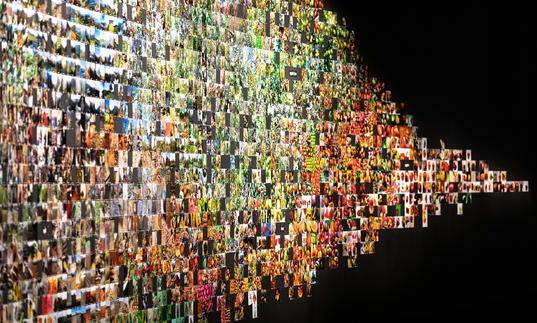

Since her 2013 debut album 8ight (released as a 3D theatre for the palm of your hand) the LA-based, British-born singer-songwriter has continued to stretch the boundaries of the role of a musician. Her innovations include reimaging the album jacket as a literal jacket by weaving her second album Montagu Square (2015) into fabric – cut by David Bowie and Jimi Hendrix’s tailor – while also releasing the record as an album deck of Near Field Communication-enabled song cards. Wolfe released her third album Raw Space (2017) as an anti-stream from the quietest room on earth and then beamed it into space via the Big Bang horn with Nobel Laureate Robert Wilson. It was also the world’s first live 360 AR experience. Inspired by the work of Oliver Sacks, Wolfe co-founded the Power of Music and Dementia study which proved that even music unconnected to memory can have a profound positive effect on people living with dementia.

It is of no surprise that Wolfe’s endless achievements will be showcased in a documentary screened at tonight’s Orange Juice for the Ears at the Barbican. A live performance, Q&A and trailer for her upcoming project on the environmental destruction are also expected. Her tireless work has led to widespread critical acclaim for both her music and innovative approach to creativity, which led to Wolfe holding a solo exhibition of her ‘world first’ album designs at the Victoria & Albert Museum and being selected as a role model for UN Women.

Her use of unconventional mediums in her artistry can confuse some listeners, unable to pin down exactly who Beatie Wolfe is. For Wolfe the inclination to box in an artist is unnecessary. ‘We've had enough examples, whether it's Bjork, Brian Eno, John Cage, of people that are operating in a space where they're combining fields,’ she says. ‘If you say you're a musician, but you do these other things, people still have a pretty narrow view of what they think it is that you're doing, or why you're doing it.’ Despite the many ‘firsts’ she’s made on her journey, for Wolfe the primary motive of every technological endeavour has been in the service of her songs, brought into the world in an era where she believes streaming services and downloads have taken the ceremony out of music. ‘I had to use these other fields to create a richer experience because music as the sole output could not do that any longer,’ says Wolfe.

Nostalgia plays a vital part in Wolfe’s inspirations, finding new and imaginative ways to recreate the feelings she had as a child listening to records. This motivation has led to many quirky presentations that truly merge the old world and the new. At the 2018 LA Times festival, Wolfe created an interactive Space Chamber exhibit using a vintage coin operated viewfinder for users to engage with her album. The simplicity of the user experience in each piece of technology has been essential to the way Wolfe wants her music to be experienced.

‘There should be no barrier to entry,’ she says. ‘It should just be that someone can pick up this weird theatre in the palm of your hand and watch this album come to life. That's the intention, that it's for everyone, and that it's inclusive.’ Though she has created a variety of new platforms from which to appreciate her work, her wish to keep music accessible is also why her music is still available on streaming platforms to ‘give people the option to engage in whatever way they want.’

Though Wolfe could be described as a futurist in regard to her presentation, her music itself is in no ways relies on technological enhancement, with its emphasis on her voice and acoustic instrumentation. The juxtaposition between Wolfe’s traditional-style ballads and her avant-garde innovations is intriguing: ‘with music I like to keep it very pure,’ says Wolfe, ‘technology can be a real distraction.’

‘When people talk about AI with art, I get so bored because we should be using AI for the stuff that we as human beings are not good at. We’re really great at art because the things that make it human and real, are things we'd never programme in the first place.’