Speakers:

EEJ: Ellen E Jones

AB: Anwar Brett

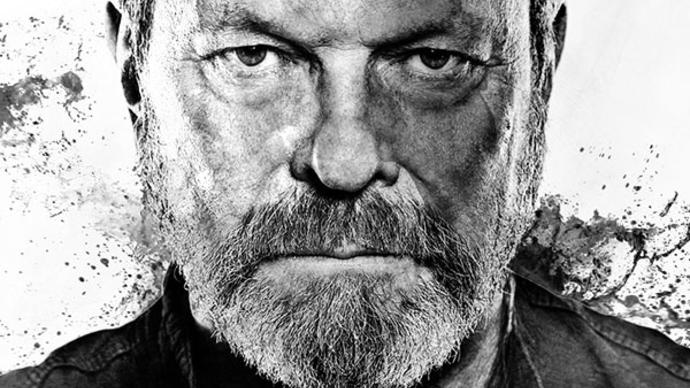

TG: Terry Gilliam

EEJ: Hello and welcome to this, the latest in a new series of Barbican ScreenTalks - where we bring you classic interviews with some of the world’s leading filmmakers, from our rich archive of ScreenTalk Q&As.

Elsewhere in the series you can hear conversations with Brighton-based auteur Ben Wheatley, and one of the boldest new voices in British cinema, Joanna Hogg.

But in this podcast, we hear from a man who’s among the most imaginative and influential directors working today.

Born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Terry Gilliam moved to the UK in his twenties, joining the Monty Python comedy troupe as their animator.

His directorial debut came in 1975 with Python’s first film proper – Monty Python and the Holy Grail, widely seen as one of the greatest comedies of all time.

Since then he’s taken us on a series of journeys into stunningly realised alternate worlds, from the surreal dystopia of Brazil, to the neo-noir future of Twelve Monkeys.

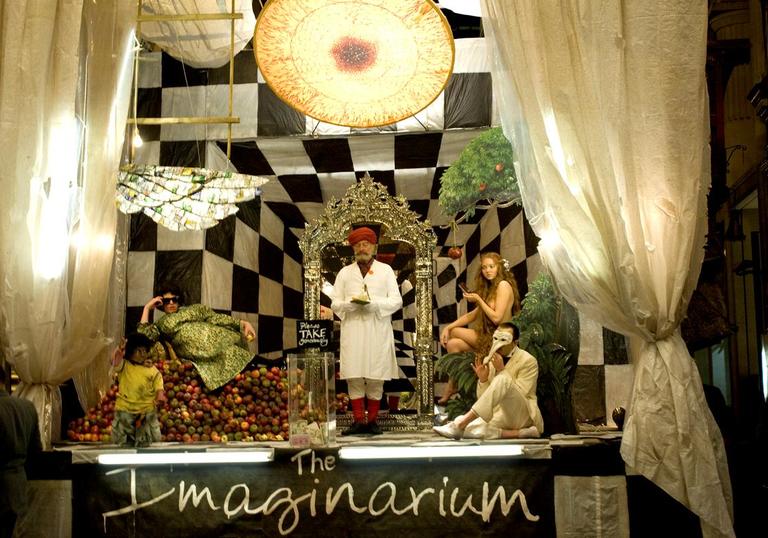

But In this conversation from 2009, Terry Gilliam talks to the late film critic Anwar Brett about The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus.

A modern fairytale about a troupe of travelling actors, the production was devastated by the death of lead actor Heath Ledger just a third of the way through filming.

The loss of Ledger meant Gilliam came close to abandoning the film, before a call from Johnny Depp persuaded him to continue. In the interview you’re about to hear, Terry Gilliam discusses the shock of Heath Ledger’s death and explains how he completed the film as a tribute. He reveals his plans for the Don Quixote project that has been stuck in production for nearly two decades.

And he is remarkably candid about his experiences working in the Hollywood machine – from struggles to secure financing to the agonies of press junkets and test screenings.

I’m Ellen E Jones and this is Barbican Screen Talks, with the visionary Terry Gilliam…

[Applause]

AB: Always a slightly reassuring sound I imagine, at these times?

TG: What?

AB: A round of applause

TG: Oh, that's what that was! Oh yes, thank you very much. You've made an old man very

happy.

[Laughter]

AB: To begin, Terry, we all know obviously of the tragedy that struck the production and I suppose the immense effort that went into bringing the film back into...you know creative life. Tell us about how quickly that decision was made and how easy it was to see how it could be done.

TG: Easy is a funny word. Easy is a very funny word. [laughs] Obviously when Heath died we were all shocked, he was a very, very close friend. He wasn't just a great actor he was a dear friend, basically to everyone involved. And it was impossible because we had been working together Saturday night, in London. We had just finished shooting, in fact, it's the scene where the theatre collapses and Percy is banging away with his gun and Heath is running after the wagon. The last shot of Heath, is him on the back of that wagon, disappearing around the corner. And we finished at midnight with that shot. I go to Vancouver to prepare for the following week's work. Heath goes to New York. And two days later he's dead. So this was basically impossible. I mean, it could not be happening. He was so full of life and energy doing his own stunts. It was, it's not happening, but it was a fact. And imagination at the best of times and then at the best of times doesn't work - your friend is dead. So I mean I basically gave up, I said it's over, the film is finished. There's no way to finish this film. And I quit. And I'm luckily surrounded by people like my daughter, who was one of the producers, Nicola Pecorini my DP who are bullies and don't respect the voice of the director! And they kept kicking me, I was down on the floor, they kicked me until I got up. And, it was a very, it was a very difficult point, you all I'm sure can imagine it but one of the things that happened I think on the second day when I was able to talk to anybody, I called Johnny Depp, who was a very close friend of Heath's as well, and I was just commiserating. And he said, well...And I just don't know what I’m going to do I think I'm just going to go home and call it quits, I don't know. And he said, well whatever you decide, I'm there. And that was a very very important moment because at this point the money and their wisdom and sense of reality and reasonableness was running away! So this film was never going to ever get finished - it was over. And that call to Johnny, when they heard about that and him saying what he said, it just slowed the retreat. And it gave us the time...

We talked about different things, people said 'oh we'll get another actor in who plays Heath' and I said, that's not going to happen. There's no actor good enough to replace Heath, and I don't want to do that anyway. And it was, it came back to London and it must have been next week I finally got my head around to the fact that let's just see if we can save this thing. Because, Amy and Nicola said we have to finish this film for Heath. You know, this is his last performance, it's not going to end up on some floor somewhere, you've got to do it. And I was saying, especially to my daughter Amy who this was her first film, really, as a proper producer, I said, you don't know any figure experienced [?] what are you talking about? I've been around, I've seen rough times.This thing is not going to be finished.

Anyway, a week later, I finally got my head into some kind of shape and I realised that OK, character goes through the mirror three times, three different people, how about that, and if we change...And if the first time, the drunk goes through if his face changes...now, oh, there's a precedent [inaudible] and he's always...the character of Heath is going through while other people are in there, we've already established the idea that other imaginations in there may be stronger than a single imagination. And that was it, so three actors - I started calling around all the friends of Heath because that was basic. They had to be friends of him. And Colin and Jude were available. Or they were able to adjust their schedules efficiently that it could slot in with the dates we were doing. And a couple of weeks later we started up again. I mean, the rewriting was surprisingly quick because with Heath not there, certain things could not be done. There were certain scenes on this side of the mirror that just could not be done so - gone! Another scene I shifted across, the one with Andrew and Jude, where Jude tells the story of the Russians, that originally was in the wagon with all the others but I thought we could do it. But later I realised we couldn't do it and all that time I kept thinking, Heath is still around here, he's co-directing this film. He's co-writing this film - he won't let me do what I want to do! And the great extraordinary thing is all the choices he made me make, posthumously, were better for the film.

AB: Just on a logistical point though, tell us how long you had Johnny for, for all that screentime you see?

TG: You look at that, we had him for one day and a second day for three and a half hours. That's how brilliant he is. That's how extraordinary that guy is. He arrived on set - bingo! He was just off and fired. And there's some very spooky things that happened. Because the last line he says in the pub when he's on the ground is, 'Don't shoot me, I'm just the messenger'. Johnny arrives on the set and says 'Can I ad lib a line?' And I say, OK, well what's the line and he says 'It's ‘Don't shoot me I'm the messenger'. And I said, what? That's the last line Heath ever spoke. And it's like, this is crazy. But I think there's something that happens... I've always had this theory that when I'm making a movie that I'm not making the movie that those that are making it are the 'movie gods' or platonic idea of the film that's making itself and we are just there to serve that thing, whatever it is. This film, more than any I've done, was clearly the work of the movie gods, because I certainly didn't do it. And it was, just an extraordinary experience because when we were shooting it, I had no idea it would work. We just went step by step, it was like 12 by 12 by 12 by 12 by step programme - just keep doing it. And the crew, everybody said, whatever it takes we're there. So, you don't very often get that outpouring of love and respect for somebody like they had for Heath. But he was special. And that's what this film is, and that's why the credit at the end is the right one. I remember we were all sitting around one night, the cast and some of the crew, in Vancouver and I said, yeah they're beating me out, I guess I say contractually it's gotta be a Terry Gilliam film I don't, will not do that. And we just talked and we all came up with 'Heath Ledger and friends' which is appropriate, true and honest.

AB: So the movie gods helped you get the movie made, do we assume that the Devil is somehow running a studio somewhere?

TG: [laughs] No, luckily there was no studio attached. It wasn't that good. If we had had a studio attached to this film, because there was no American money evil stuff [laughter] it would never had happened. There was no studio that would allow us to continue to do what we were doing to have Heath, hanging from bridge for his entry, with lines like 'Why are you fishing dead people out of the river?' He's dead. They would never allow that, it was interesting, there was one line and I said, we are not changing the script, the speech that Johnny gives about Princess Di and everybody never growing old, that was all written before, it was not a eulogy for Heath, that was all there. And there's a line in the monastery at the beginning when Christopher is talking about stories, comedy, a romance, a tale of unforeseen death - we had written that in advance. And he didn't want to say it and I said, we have to. This is the film Heath and I set out to make, we continue that film and we do not compromise it. And so we were very lucky not to have well meaning, decent thinking people involved in this film [laughter] because what we have is something that's honest!

AB: But in all reality any Hollywood studio, any studio would have protected its asset by cashing in the insurance bond?

TG: Oh yeah, there's no question. I mean, that was the easy way out. I'll tell you something, I haven't mentioned this - here's how bad it was... Here's how films get made. You're in on a secret. Films start, because when you're doing an independent production like this, you've got a bond company, which guarantees that the film will be finished at all costs. Now the insurance company does many things but one of the key things in this instance was it insures the essential elements. There were two essential elements – me and Heath. Then there's the bank, that we've just had to sign a contract with. There's one other thing, and it doesn't matter. All these contracts were not signed when we started the film - that happens all the time - but the deals are basically there, it's honour, word of mouth, all that stuff - but the contracts were not signed. They were nsigned only four days before Heath died. And can you imagine what the financial people were doing? They had just signed away all this - and then, it's gone! We're doomed! And so there was panic. Absolute panic. But the call to Johnny was the key.

AB: Just a quick word about Christopher Plummer, you mentioned him as Doctor Parnassus, I mean, he's a wonderful actor getting great roles at an age when other people might be thinking of retirement. But tell us a little bit about his contribution to the film?

TG: Oh, Chris is the tent pole, he is the centre, he holds up the whole circus. We worked on 12 Monkeys together and I really liked him. And he is one of the greatest actors still standing, I mean, he's extraordinary. I keep saying if there was ever a Mount Rushmore for thespians, Chris would be the first head up there! And, he was, he is just an extraordinary performer - I can throw the most silly ideas at him and he gives them the most grace and then, I sit there and I say, OK, Chris, get this, you've got a double act with Tom Waits, OK, I've got a double act with Lily Cole, she's not acted before, and you've got a double act with Verne Troyer, you know the shortest guy ever in showbiz. How you feeling about this, Chris? And he's just exceptional. I just think watching him is a constant wonderment. I mean, I think for anybody approaching the business, you know acting, just watch that. And that's what's interesting, for someone particularly like Lily who had never really done any acting before one little bit in St Trinians, and she was surrounded by these brilliant actors. She's so smart – she watched, she watched and she learned. That was incredible.

AB: Let's have a question...

Q1: If he hadn't sadly died, what trajectory would Tony's character have taken? Was he destined to go through the mirror three times originally?

TG: He would have been what you saw - except it would have been Heath doing it rather than Johnny and Colin. I mean, that script didn't change. What Heath had planned to do, I don't know, all I know is what he had done is he had created this comedian character in the bits we saw. Because that's what Tony was about - one minute he's the Aussie, the next minute the Cockney the next minute plummy English. He was everything, he was fluid. He was building up all sorts of goodies for the other side.

Now, we will never see that and for me, however wonderful this film is, and I do think it's truly wonderful, I would like to see that. And we'll never get to see it. Just like Heath will never get to see this movie and that was why he joined up. I said 'why do want to do this?' and he slipped me this little note and it said 'because I want to see this movie'. And so, the god of irony is winning today.

AB: Perhaps you could expand on that story, because, he approached...

TG: No, I did a very subtle dance. I'd like to take credit for it but if I was planning any of it subconsciously. We had a great time on Brothers Grimm, I just loved Heath. He was just so exciting to work with because he was so full of energy and ideas and there was a gravitas about his work. However silly he might be, it was always grounded into something really, really serious and profound. And after, Brokeback Mountain, he went through a rather strange year. Because here's a guy who did not like whoring and prostituting himself and going onto Oprah Winfrey and all that world of promoting a film. He just didn't like doing that he always sort of closed up. He felt that's not my job, my job is to be as good an actor as I can and not just a hustler. And the Brokeback Mountain thing, I think really bothered him. Because he went out, and in his ideas, probably sold his soul and then nothing came of it. So there was a very funny year after that where he was saying yes to this, and no to that, trying to stay somehow true to what he felt he was and what he should be doing. And there was a couple of projects I'd thrown at him that were sort of a yes and no and...it was a confusing time. So I was sending - because we were very close friends - so I would send him stuff, let him read it, but never ask him. And he was over here in London working on the Joker, and he was working on an animated video for Modest Mouse, a pop group that he directing and it was his story and everything, and he needed a place to work. So I put him to work at Peerless Camera Company over in Bedfordbury, and he was working there. And we'd see each other when I was there, and blah blah blah.

And there was one day I was showing my storyboards to the effects guys and talking through all these scenes and in the middle of this, Heath was sitting there, and he slipped me this little note in the dark there and I opened it and it said 'Can I play Tony?' And I said, are you serious? Yeah, I want to see this movie. And I though at this point - money, no problem. 25 million. Go to America, piece of piss. This is easy. And we couldn't get any money out of America basically. This is the frightening thing about that lovely little village called Hollywood - there's a lot of inbreeding going on there - that's why the mental state is a bit limited! And it's frog feeted people, bat eared, strange inbreeding goes on there. And I'm saying, wait, this is the end of 2007. This is what's going to happen, somewhere in 2008, A Dark Knight is going to come out, Heath Ledger is the Joker, he will be the biggest star on the planet when that comes out. We are the next film, we'll be coming out a few months later. Does this seem like a good deal? And he just blank stares. Blank stares... He couldn't imagine 7 months ahead of him. These are frightened people, terrified of losing their jobs. And in fact they are losing their jobs - most the people I talk to are gone! [laughter]

AB: OK, we have another question, just behind that row...

Q2: You spoke before about the extraordinary Johnny Depp and your ability to bring films back from the brink. Just wondering if we might get to see the return of Don Quixote La Mancha?

TG: Whoa! Err...Don Q has got three legs on it at the moment, the horse I had is, I've rewritten the script. Tony Grisoni and I had a major rewrite ever and we're going to get back after 7 years in the French legal wilderness. As scales fell from my eyes, I was blind and now I can see! [laughter] Quite honestly, 7 years of being away from that script, not reading it was the best thing that could have happened because suddenly I realised this wasn't as great a script as I had thought and I think what we've done it really good. But maybe again I'm fooling myself, but I think it's really good now. Johnny is a bit busy doing Pirates 12 [laughter] and The Lone Ranger and everything. His dance card is very full. We've been talking and I said I can't wait, Johnny. I'm doing it next spring time. I want you, but I'm going to do this thing. I'm going to die very soon.

So at the moment I don't think Johnny's in it. So I'm thinking, it's a new film, starting again. But I think I've got Quixote, that's the main thing.

AB: To an outsider, Terry, the character of Doctor Parnassus would seem to share a lot of things with you... Did that come about when you were writing it? Was that the intention going in that it was an expression of some of the experiences that you've had over the years? Trying to realise these visions?

TG: I wasn't thinking of it that way, I always said this was going to be a compendium of everything I've done. It's the first original thing I've written with Charles McKeown in a long, long time, so it was a summation of a lot of things I'm thinking, feeling. But it's Charles in there as well, we're both getting old and miserable and it's, yeah, at a certain point you'd think, wouldn't it be nice to get bigger audiences, wouldn't it be nice to be Stephen Spielberg, but that's not going to happen so, there is that. And we invent this character. It was an interesting writing process, because we had no plan, we had no story when we began, just this ancient theatrical wagon arrives in modern London and nobody's paying attention to this extraordinary, wonderful thing that's being presented. And that was it, we just slowly built this together, a character here, a little thing there, we'll go through the mirror, and then there'll be this incredible fantasy. And I remember Charles saying, you've got to call halt that at some point, you've got to have a cross roads, you've got to have a choice. And once you got a choice there's got to be a choice between good or evil, or better or worse, whatever, or whatever the good side is, the worst side we know who's waiting at the end of that one, that's got to be the Devil. So suddenly we have the Devil in this film! And it was a really interesting process to start and build like a piece of sculpture, where you add and take away

AB: OK, we have another question, just here

Q3: You just mentioned the Devil, was it intentional to cast Tom Waits because he's played God in another film and now he's gone to play the Devil in yours?

TG: Well, it was funny because we had written it and there was a Dutch animator friend of mine who wanted Tom to do a voiceover in his animation and he wanted me to get in touch with Tom, because he knew I knew him. So I sent this stuff to Tom and Tom said, I really don't want it...have you got...have you got anything for me, Terry? And I said, well, I got the Devil! And he said, well I'm in! I mean, he didn't read the script, but, done. I mean, he's the perfect Devil, I can't imagine anyone...I mean last night in an interview someone said, 'here's the man who writes songs for the angels and sings them with the voice of Beelzebub'. Tom is one of the most extraordinary geniuses on the planet, I mean, nobody writes music like that. The most sublime, romantic sentiment music to the most dark and disturbing and strange what is he doing in here? He's just brilliant. And he's a great actor. I actually wanted to use some of his music in the film and he said, please don't, let me just be an actor.

AB: I don't imagine Christopher Plummer has a lot of Tom Waits CDs [laughter] but did he know of Tom's body of work or at least his reputation before?

TG: I never know. Christopher is a mystery. But the minute they got together it was just like two old musicians. I mean, acting the way Christopher does, that's a musical talent he has there. The voice, the rhythms, the pauses, the space. And that's what Tom does. And I just thought together, that was one of the great love stories of all time.

AB: Tom didn't serenade him with the chorus of Edelweiss or anything? [laughter]

TG: No, that was how you got Chris' goat, anytime. [sings Edelweiss] Or 'The hills are alive...' and then daggers would fly through the air. It's so funny how he really hates that. [laughter] We all love him for that.

AB: Absolutely.

TG: Yeah

AB: You talked about this theatrical wagon appearing on the streets of London, I suppose not so very far from here, some of those street scenes. TG: Indeed AB: All night shoots, I suppose. What was it like, was it easy logistically to achieve that, against these real historic backdrops

TG: I mean, it's always hard. It was night, it was the middle of winter, December, freezing, horrible. I mean, the opening shot is over in Paternoster Square which we can see from the restaurant. It's there and it's this dark side of St Pauls, because the lights leave a shadow on the dome. And that really intrigued me. But to drag that wagon, or have the horses drag that wagon across that square we had to lay down a rubber road for a couple of hundred metres to protect the pavement. Those were the interesting nights.

AB: If anyone else has a question, perhaps it would be a good time... [laughter in audience]

TG: Oh, there's somebody...!

AB: The microphone is flying...

TG: Oh, she's getting too excited, quick

AB: It's coming towards you now [laughter]

Q4: I was also wondering, what's the quickest you've ever written anything?

TG: Oh God...oh it was only the Python animations that were quick. I don't write quick. I sort of, I don't know how to write. I sort of discover things, is what it is. You sort of work your way through. I mean, when you're adapting something that's easier. I mean, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Tony and I did it in eight days. So, it was like, OK, you take this book, we're going to be gonzo screenwriters. And we did eight days - whoa! Done. Then we all went our separate ways. Tony went to his place, I went to mine. We read it, we called each other. Next morning to say it's crap. [laughter]. And we then spent two more days, and finished it. [laughs]

But that was because we thought, we know the book well, there it is in front of us. It's an editing process, really. You make some decisions about how you're going to approach something and then you edit, because the book is there. In that instance, we made a very simple choice about what the book was about. It was our version of Dante's Inferno. And Dante and Virgil had a little trip into the layers of Hell. Now, Dante is a Christian, Virgil was a Pagan. So, if you, we decided on the book and we think it's all justifiable that Hunter, Doctor, Doctor Thompson there, is a Christian, because there's a certain morality at the heart of it. It's enraged in what the world has become. And Gonzo, we thought should be a Pagan. And that was the approach. And once you do that, things started falling into place very quickly.

AB: When you come, Terry, every so often to go and do those rounds of meetings in Hollywood to go and speak about future projects, is it constantly having to reapply for a job? You're always having to re-audition in a sense, even though you have this tremendous body of work and you know, the many years of success. Do you find they always automatically know, or do they simply look at the list of box office numbers...

TG: No it's like the script, I know exactly the script when I go in there so it's like doing a play. And the script it's always like 'Terry - god, it's good to see you! Just love your work! I have just loved everything... I remember when I was a kid, Time Bandits, oh it changed my life. I have loved everything you have done, Terry'. And then I say, well, what do you think about The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus? 'The problem, Terry, is I'm not sure really if this one works...everything else has been great'...Now I've heard this for 25 years. I mean the list gets longer of what they've loved and which films have changed their lives but it's exactly the same scenario.

[laughter]

I know, I don't know what I have to do! I keep thinking, now if I make a lot of money for them it'll be easy. And it is true, I mean, you know The Fisher King did very well, that was the first film I did, well, Brazil is really a product of the success of Time Bandits. And then Munchausen was the punishment for getting away with making Brazil. And then you have Fisher King which was the first thing I made in Hollywood that I hadn't been involved in writing but it was the most brilliant script, I thought. And it was a big success. So 12 Monkeys became easier. But it wasn't going to happen until I got Bruce Willis and Brad Pitt - so it wasn't that much easier actually! And then, because that was successful, well, what was the film I did... Fear and Loathing got off the ground with a little bit more ease. But even in those, it's really surprisingly difficult because each one is not like the one that preceded it. And Hollywood only thinks in franchise and sequel terms, that's all.

AB: So, at any one time, and notwithstanding the Don Quixote project you talked about, how many other things do you have bubbling away that you can perhaps work on and concentrate on?

TG: They don't bubble, I don't work on them, I don't concentrate on them I put them in a drawer and forget them! Basically, because I spent most of my life on these things. You've just got to - enough - I mean there's Good Omens which is based on the book that Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman wrote. Absolutely brilliant book, we wrote a great script that Neil and Terry are very happy with. This is one of the biggest books ever... I don't know, 11 million copies, it goes on. Can you get it to Hollywood? I think first, we've got to do it in a comic book form and then they'll give us the money. You've got to draw it first now

[laughter]

AB: So in terms of the fate that awaits Doctor Parnassus, what about the American opening?

TG: Well, the deal was finally completed a month ago. And it opens on Christmas Day. Sony Classics have it and they open in New York and LA on Christmas Day. I mean, having not got the American money to start this project, we did it with UK and Canadian co-production, off edged by German, Italian, Spanish and Japanese presales, we did it. Completely separate from that world. Then I thought, now we've got Heath Ledger's last film, we've got Johnny, Colin and Jude. We're going to go out there and they're going to pay, pay and pay to get their hands on this thing. And that's not what happened.

[laughter]

I mean, my timing is permanently bad. There was a little thing called the credit crunch. The world collapsed. And suddenly Hollywood just panicked and we ended up getting less money than we were being offered that we didn't take the first time around. It's amazing. But, I don't know, the guys we've got, Sony Classics, they're going to do a great job. A lot depends on how it does here in the UK. Because if it stumbles here, Hollywood panics. What's interesting, I've always railed against the power of Hollywood, the machine, how we don't get to see independent films, smaller films, because we're up against, you know, $50million marketing campaigns that Hollywood does. I mean, it's huge machinery that basically wipes out everybody's memory for anything else but that film that's coming out that week. That is being sold to you 24 hours a day, every time you turn left, right or look up and down! And so, I got my wish. So I got a film that's opening in England first, which is absurd. And then it'll open in France, which is... It's going all backwards! And what will happen is the pirated versions will be in America before it opens in America- this never happens to America!

It's what happens to Europe and the rest of the world and now, I'm getting my wish! But it's my film that's getting punished! [laughter]

AB: We have a question towards the back...

TG: Yeah, shout!

AB: I'll repeat the question

TG: I think, are you an actor? Can you pro-ject? [laughter]

Q5: Unfortunately not.

TG: But your voice is lovely, I can hear it!

Q5: Thank you! Do you ever read press reviews of your work? And if so, do you get annoyed with them?

TG: Yeah, it's the one thing I keep trying not to do and I really can't, I keep peeking. And it always hurts. I mean, I don't mind a bad review if it's an intelligent bad review, where they actually understand what one is doing or why one is doing or what one's trying to do. But just crap reviews, written by some jerk who had fifteen minutes to write it, makes me angry. I mean, we spent three years doing something and somebody who's got a deadline he's gonna knock it out in fifteen minutes - ah ah. It's actually a very bad system now, because the newspapers, the editors are pushing a lot, creating a situation where on the Thursdays, or whenever it is, all the films of the week have to be reviewed. And this is nonsense. A reviewer should write about the things that he's passionate about. Whether it's positive or negative and then let him go at that. But now, everything has to be done equally so you've got guys writing reviews on something that just, there's no need for it. Either it's a huge big film and it doesn't need it or not, there's no space for properly considered reviews where people are spending their time. I mean, I'm not a big fan of critics anyway, that's beside the point, there are good critics, and there are bad critics. There are people who aren't even critics because they have no idea. They are writing for the audience of the newspaper, not about what they think. That's like being in a focus group, when you do research screenings and people start saying, 'well I personally liked the film but I don't think it will work for Johnny down the block or the people over there or the people that vote Republican' I mean - what are you talking about?

All you want is one person's opinion - that's all it's about. And you can agree or disagree. But at least give the work that people have spent a couple of years to do, give it some respect. You can tear it apart but do it with intelligence and understanding. It makes me crazy, I mean, this film as a Cannes vessel which I think was a big mistake because they put it on in the penultimate night. People are tired by then, everybody has been watching - how many films do you watch, three or four a day? This is crazy. And the press screening is at 8.30 in the morning. At the end of two weeks almost. People are knackered. And you go in at 8.30 and you get beaten up by that? I mean, I get angry. it's just no way to treat the stuff but the system is demanding that. I mean, they don't even review new jeans as quickly as that. They wear them for a week to feel their work. Whatever the fashion magazines, they consider before they write about the new jeans or socks, whatever it is

[laughter]

AB: So whose opinion do you seek out on each new project? Whose view matters most to you? Is there someone close who always gives you...?

TG: Not really, I mean one of the things we've always done, and this started with the Python days, when we're cutting the movie, early on you start showing it to people. You bring in friends, you know, neighbours, and you start talking about it. Are we communicating clearly? Were you bored? What don't you understand? And it's easy to talk to people when the film is in an unfinished form. It also can confuse you because you don't have all the music on, you've got key elements that are essential but, if you, you know, if you listen carefully and don't panic, you learn when you're achieving whatever it is you want to achieve. So, by the time I've finished with a film, I know it's working as best as it's going to work and it's working the way I want it to work. And you know whether a lot of people like it or a few people like it. So by the time we go to these pseudo-scientific screenings and the research screenings, I'm never surprised, I know what's going to happen, I know how it works. So I think they're surprised because they think I'm this arrogant, pig-headed guy who just does what he wants to do, but it's not that at all. I really want to reach people, I really want to get to them. And so I want to do it as efficiently as I can with what I've got. And then when I find that a reviewer has been up all night and he's got to come in before breakfast, and blearily look at this thing, it just makes me crazy. I mean, come on. We've done some work. It's like we're publicity for the movie, which we've been doing a lot of, you're put in a room and you can be in any part of the world, the curtains are drawn, there's usually a poster behind you, there's two cameras, and every five minutes somebody with their own television show walks in and does a five minute interview. It's the same questions, it's the same answers, it's the same pretending I've never heard that question before - and aren't you interesting! I mean, when I did Brothers Grimm - 72 of these things in one day. Now that's a really mad way of selling a movie! And it's really bad in America, because they come from all over America, in their little podunk town they're a superstar with their movie show. 'Hey, come in to my world - I'll tell you about what's in the screens tonight. Let me tell you about me first, though' And then like that, and they come in, and you're dealing with these flaming egos that think I'm supposed to remember them from four years earlier when I had five minutes with them - because they're my best friend now. And, you start going absolutely crazy. Making this film is the easiest part of the process. And it's, every one of these things, somewhere around 50, I'm having out of body experiences because, it's a mantra what you're saying again and again. And suddenly you start floating up there and you realise the body is down there and you're on autopilot you could do anything! Whay! Look down there. I mean, I shouldn't be complaining because we're lucky to do what we do. And we go out and you beat the drum and you do it every day just to help bring people to see the work of a lot of really wonderful people, so.

AB: We've got two last question then, if we can get the microphone... Three last questions!

Q6: A quick one!

TG: She's ready...

AB: Don't expect the Spanish Inquisition!

Q6: I just wanted do know, how important is the art for you? And how much of Terry Gilliam is in the art direction?

TG: The thing about making movies for me is that I get to do everything. And every bit of the movie I'm involved in. And this one I actually storyboarded, I designed a lot of it, just because I enjoyed doing it. I mean, everything is part of the process of telling the story. It's not just a set, the set has meaning, it's a character in the film, always. So I spend a lot of time on the design of the moving. Because you're doing a painting, all pieces have to be right. Everything has got to support the characters and the costume, every actor comes in and spends a few days sometimes - and you build the characters with the clothes they're wearing. Sound, everything - I mean, I do everything. But the trick is, I hire people who are better than I am at each of these jobs. And then the fun begins. So I have an idea and they come up with a better one! Oop - I've got one to top you! Oop! No you don't. And it goes like that. And so it's a joy. We really have a great time working in this collaborative, leap frogging fashion. But no, I've got to be involved in everything. it used to terrify me when we did the music on the film because it's like, the music is, I don't know, it's so powerful, and I used to always sit with the composer by the piano together and say, no ignore that. Because most films that hand it over to the composer, it's like giving your kid to another parent to raise that child and then come back in a few years to see if it's the same kid. And that's why you've got to stay close to these things, every bit of it.

AB: We've got another question

Q7: You recently said filmmakers are expected to film their films in 3D, would you want to? And do you have any plans to capture these vivid imaginative films in 3D?

TG: Nope. [laughter] 3D costs a lot of money. And if you have a lot of money, you've got to start simplifying your ideas. And I don't wish to do that. I don't think 3D makes a blind bit of difference, honestly, I've seen 20 minutes of Avatar, it's beautiful. But after a while, the 3D becomes normal, so what's it about. This is like what we did with Parnassus, my theory was because we had a much smaller amount of money to deal with than the big boys, let's do this thing where every time you go through the mirror it can be a different world. And you don't stay in there too long before it gets too expensive - and you get out! You do something, say Pirates of the Caribbean where you're spending, I don't know, $200-$300million, after a while you're in this world and it's normal after the first 15 minutes and so, where are the surprises? To me, if you're dealing with anything, it's about surprise and catching people off guard and astonishing them. I was watching Avatar in the cinema, and really, it's quite beautiful, but you need $300-$400 million to do that. I'm not going to get that money, I don't want that money, I want to have the freedom to play and to astonish people in a different way with ideas, get them thinking. I think what 3D will be, just like it was in the 50s, it will perk things up for a bit, I somehow think it's longevity is not that much guaranteed. It's still about stories, characters, all of those things. I mean, Avatar is very impressive but I have a feeling I've seen it before.

AB: We have another question, just there

Q8: The film reminded me of Baron Munchausen because of the atmosphere and this man and his theatre and his daughter and everything and I was wondering what you thought about it?

TG: I think it's probably closest to Time Bandits and Baron Munchausen than anything I've done because they were the original things I was doing. I mean, Time Bandits has a theatre as well. It's that business of a travelling show which I've always been fascinated by and whether it still has any meaning or relevance to the modern world it's like that in both films. The theatre there is just in the way of the reasonable, rational people - it may be the solution to things. This one, again, nobody is paying attention to it but it might just change your life, if you spend a couple of minutes, pay your five quid and go in. Most people are not paying to go in there - watch the film. Actually the women when they come out, that's when the money comes out. Up to that point, people have been sneaking in, cheating. It's like I was a kid when the circus came to town and you'd sneak in behind the canvas. That's what was going on there.

AB: Please will you join me in thanking Terry Gilliam

[Applause]

EEJ: Thanks for listening to this Barbican ScreenTalk with Terry Gilliam.