Speakers

EEJ: Ellen E Jones

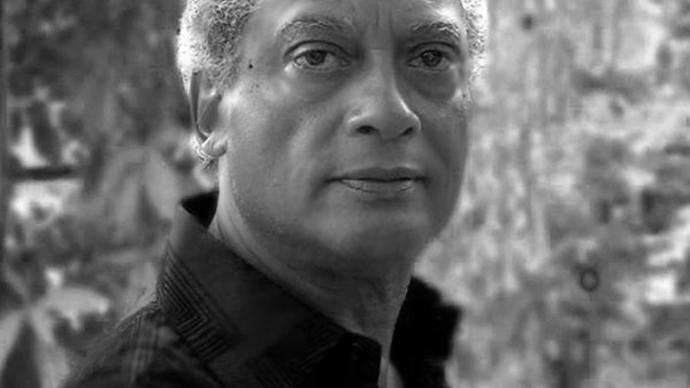

HO: Horace Ove

JA: John Akomfrah

EEJ: Hello and welcome to Barbican Screen Talks, where we release our pick of the best interviews with filmmakers and film fans, recorded at the Barbican Cinemas and stored in our vast ScreenTalks Archive.

So far in the series, we've heard in depth discussions of British films including The Wind That Shakes the Barley, High Rise and Belle. In this latest podcast, we bring you a frank conversation with the man behind the first black British feature film.

Horace Ove with part of a wave of Caribbean artists and intellectuals who arrived in Britain in the 1950s and 60s. Born into a large bohemian family in Trinidad in 1939, Ove came to London to study art. He began his career as a photographer, documenting leaders of the Black Power movement such as Michael X, before turning to directing in the late 60s. Ove has had a diverse and exceptional career, including celebrated documentaries like Reggae and A Hole in Babylon, pioneering British TV programmes such as Empire Road, and even appearances as an extra alongside Elizabeth Taylor in Cleopatra.

But in this conversation from 2005, Horace Ove talks to his friend, experimental filmmaker John Akomfrah, about 1975's Pressure. The first feature film to deal directly with contemporary black British lives, Pressure was funded by the British Film Institute, and, controversially, held back for two years before its eventual release to widespread critical acclaim. Pressure was co-written by fellow Trinidad born author Sam Selvon and follows three generations of a Trinidadian family living in West London's Ladbroke Grove. Herbert Norville stars as the family's youngest son, British born Tony, who grows more and more disillusioned as he faces unemployment. Alienated from his white friends, he follows his older brother into the Black Power movement.

In the interview you're about to hear, Ove reveals how the issues explored in Pressure are still relevant to the black British experience today. He discusses his early exposure to cinema, growing up in post-war Trinidad, and he explains his refusal to be pigeonholed as a black filmmaker. But first a warning. This is a frank discussion about race and filmmaking, and so features language that may offend some people. Also, like the making of Pressure, the recording of this ScreenTalk was a somewhat lo-fi production. This means our mics didn't quite pick up the audience questions. So I'll be back later to help out. I'm Ellen E Jones, and this is Barbican ScreenTalks with Horace Ove.

JA: Okay, folks, and we're not gonna hog too much of the limelight because I know you've all sat there for a while. So you probably want to say things yourself. What I want to do very briefly is to say a couple of words about Horace, ask him couple of questions and then...

[Applause]

Is that alright?

HO: Yeah, alright! Go with it.

JA: Well maybe we should just jump in? What do you think about it now looking back on it? Just because we were both standing there watching it.

HO: When I look back at it, and it's all from this perspective, and many years after, I mean, it. It looks kind of rough and dangerous and all that sort of thing and the way it was pulled over, but a lot of it happened. A lot of what was going on there was reality. And maybe this is why the photographs outside were simple because I took all those photographs, and many more, before making the film so that all that research went into making the film and being part of it and seeing it. And although after that we made the film, it was banned for nearly two years before we can get it out. Some of the critics, good critics, saw it, wrote about it, and it was released. But I could see from lots of people, pointed in perspective how frightening it could be, because they were not in that world. You know, they were not experiencing what was going on, especially white people in the country.

JA: I mean, Pressure was - maybe I should just incorporate what I was back to say into the question - Pressure was, for me the end of a cycle, but started Boardrooms Nigger, you know, basically, your independent cycle, when you do a range of stuff, principally about black struggles, black politics and black figures. How did you make the shift from a kind of marginal, institutes won't talk to you, to the BFI, which would have been at the time, you know, it would have been the Film Council of it's day.

HO: Well the BFI didn't really want to do it, to be quite honest. We took that idea around television, different companies and everybody turned their back, and the BFI was a bit worried about doing it at the time also. And I think there's a few people got together and said, Well, you know, let's see what could happen, you know. Black filmmaker might make too much of a good film or whatever. Let's try it and put it out.

JA: But so, what, you had the idea and then you went to them or...?

HO: No, no - we'd written a script and everything. We'd written a script independently, you know, myself and Sam. So we wrote the script. And we had it all ready to go. And then the BFI eventually agreed to do it and finance it - it wasn't a lot of money but a lot of my friends, at that time in the film business and that who I went to film school with, and who we came together, and I just know. And the majority of them were white filmmakers, who, you know, was part of that whole 60s politics who understand it and knew it, you know, got together and said, alright, we'll give you four to five weeks to shoot it, let's go for it. After that, you know, we got to go on to other films that earn some money. So we went for it. And we did it

JA: Pressure's extraordinary for all sorts of reasons. And one of the main ones, for me, to start with the top, was that it was a collaboration between you and Sam Selvan. And in a way the film highlighted what was unique about you, because of course, anyone that had seen the documentary you did recently about the Caribbean Arts Movement, would know that you arrived with a whole range of titanic figures in the Selvans, the Salkeys, and yet out of the whole crowd, you were the only one, you know, occasionally someone would write the odd play - but you were the only one those major intellectuals who came from the Caribbean at that time in the 60s and turned to cinema? Why was that?

HO: Cinema was always in my life, from the age of 12 in Trinidad. We had the cinema and I don't know, maybe, I guess from the 40s right through the 50s and 60s, you had about six American bases in Trinidad, who was training their soldiers in guerrilla warfare and all of that, and they used Trinidad to do it, and they will serve cinemas to entertain them. So therefore, there was about two, three hundred cinemas over the place and we were exposed to the cinema. And we got involved in it. Also at the same time, because Trinidad is such a multicultural kind of place, we saw French film, films from Spain because the people from all over those parts of the world were there. And a group of us got into films quite seriously. You know, and that is going back to long before I came here. So it was part of my life, even then. You know and then coming to Europe and living here for some time and then going to live in Italy 1961 when I was working on the huge film - Cleopatra.

JA: We want to know how you met Elizabeth Taylor

HO: Well...

[Laughter]

JA: Come on, don't we folks, we do!

HO: No, no, no - I was in Cleopatra, I think it was around 61, here, and they built a huge set for millions of pounds and all of that. And they hired a lot of local people and extras and stuff and myself and my cousin, who's an actor Stefan Kalifa, got a job on it. Because we had this kind of brownish colour so we could be in the crowd and look like Roman soldiers in the sun. But you were standing out in the freezing cold and they said, 'ACTION!', and you throw it off and you look like you're alright. And then Elizabeth Taylor got fed up of that, got fed up of the lead actor - I can't remember his name right now, from Australia - fell in love and Richard Burton and said 'Let's bring him in! He will be the lead actor and let's move to Italy!' So the whole film moved to Italy

JA: Including you...

HO: Including me and all the other brothers from here, you know, we went off and I was made a slave in Italy as soon as I got there. There was no more Romans!

JA: No more Romans.

HO: No more Romans. But it was great for me because it really exposed me to another sort of cinema that whole kind of realist cinema, surrealist cinema and that world, and all that was happening in Rome and Italy at the time, and that really messed my head up and broke me away from the kind of Hollywood movie, which a lot of it I could still see in Pressure.

JA: The other thing which is really extraordinary about Pressure, was a quality that I always associated with you from the minute I met you. I remember when we used to come up to see you in the early 80s, 'Can you teach us this, can you teach us that!' And you said well... The quality you had that the other figures, that I've talked about, you know, you and John La Rose had this quality. It was this ability to embrace what was going on here, even then, you know. You seem to be able to be in that world. The world of the Caribbean, and this one at the same time. And Pressure has that, doesn't it...

HO: I think that goes back to - back home in Trinidad. Which is something that everybody's discovering, you know, but it was such a multiracial society in general, and everybody was mixed up and all that sort of thing and people came together and hang out, no matter what class, what colour, because of the carnival would come on every and everybody came together. And it kind of prepared you for the rest of the world. I mean, just the other day I was trying to explain to somebody when I came here, and I saw paintings by Picasso and Salvador Dali and all that sort of thing. And I didn't make a fuss about it. And everybody said, why not, it's history, modern art. You know, but you grew up with Carnival, you grow up with guys walking down the street, five o'clock in the morning coming out as a monster, the dragon, the bats, somebody jumping out of a tree - so it's a very surreal world. That's one side of it, the other side is people came together. So all of you in Europe and you had all these racial problems in Europe, you were still not trying to go around hating everybody. Because in Trinidad you knew every class and every colour and you grew up with that. So you, you went out there and try to do something about it. You know,

JA: The film was a departure for you one significant respect. I know there have been, there are other films and there was a great moment when you showed me this unfinished, short fiction that you done...

HO: Yeah well. There's another side of me as a filmmaker. It wasn't just, I mean, it was important to make all the social political films at a time because you came into it and it was happening around you, and as a filmmaker and a photographer, I got involved and it was there and it was wrong, I wanted to do something with it. But as a filmmaker myself, you know, you have other ideas you have, you know, as I've always said, you don't have to make social political films all the time. You can as a filmmaker and as a black filmmaker... And this thing about a black filmmaker was you can only do this, I mean, you're a filmmaker, no matter what your colour is, guys, you're a filmmaker. I know, they like to put you in this black rubbish bag and bring you up every year together. To know, you're a filmmaker, and I would love to make - and that's what I did. I had the opportunity to do a few of those and go to do other subjects. You know, I did The Professionals and all that sort of thing and, you know, just to break away from things. But the whole political thing was very strong. I was there and one had to do it - it's like the film I made on, A Hole in Babylon about the Spaghetti Siege and all that sort of thing.

JA: But there is that thing, there is there is that thing, there's a kind of political humanism in your work.

HO: Oh yes. But I try to come take it out of reality. I mean isn't Pressure and seeing Pressure there, a lot of it is what I experience with different families and people in every sort of thing. I know sometimes I show Pressure, and everybody, a younger generation, is embarrassed about the mother, Lucita, but she's the realest woman and women like her from in that Windrush period that came in was upset and screamed and cried. They used to put them in a mental home at one time here. And thought they were having a mental breakdown. They now discover, after many years, it's the right thing to do scream, cry, shout and clear your head. And she was doing that and I know a lot of even black critics were very embarrassed, 'How could you show us like this?' You know, how could you do that? You know, but she's real.

JA: Would you do anything differently with her now?

HO: Well, her generation is gone. You know? I mean, you guys are now British. So we have to deal with you! This is what the film is about is for kid trying to find his way in those two worlds, you know,

JA: Before that, a lot of the work had been documentaries, what was the impulse to go to to drama?

HO: No, drama was always there. Drama was before documentary

JA: Explain...

HO: Documentary was there because I like making documentaries, because documentaries expose you to reality, you have to go out and you see the real world and you make films about it. That's why I made various documentaries, because of that. From music documentaries to political documentaries, the Bhopal I made the first film in Bhopal about the gas disaster and different things and the first thing on reggae music and various things. I love documentaries and documentaries expose you to real life and real people

JA: Pressure is kind of blip isn't it? Because immediately after that you really do get into documentaries in a big way.

HO: Yes, yeah. And Pressure has all of that in it. Pressure has a mixture of the documentary, the drama, the kind of surreal filmmaking. The world outside here and the world that is going on in his head, which is very frustrating for most of us. It had to be expressed, you know, sometimes we just make a film about what's happening in front of us. But we never make films about what's happening inside of here. You know, while you're talking to me and while I'm saying something and people are sitting out there - there's a whole lot of other things going on in each person's head. And I saw that on the European films and that really interests me. And it's something that I've learned growing up in Trinidad to people talk about the dream, talk about their head... And that is what came out also in Pressure.

JA: I mean people always, you know, because we started saying it is now kind of fashionable to say because it's true, that you are our pre-eminent director, but of course, when they say that they usually mean filmmaking, but of course you're also a major innovator in television. A whole spate of work...

HO: Yeah, there was quite a lot of it

JA: You were first. So Empire Road..

And Orchid House series. And then I did Latchkey Children, which was kind of multi racial thing about a bunch of working class kids, white, black, foreign, who was living in a neighbourhood, you know, and they're wronged. The only pleasure they had was this little playground and this swing and they were breaking it down and they all got together and got to the House of Parliament... There's quite a few things like that that I did for television.

JA: Do you regret that in some way because one of the most extraordinary films ever made in England in the 70s. And in a way people had seen it before they'd realised that you invented a drama documentary. You and The War Games man - is a film called A Hole in Babylon. Because it was shown just on television

HO: Hole in Babylon was banned for a time

JA: How did that come about? Just so that people know, Hole in Babylon was a drama documentary that Horace did about the Spaghetti House siege of 1980 something...? '76? '77?

HO: Yeah. A lot of people might not know about the siege. Which is the first major siege in England and was done by three black guys - two West Indian guys and an African guy - who held up the Spaghetti House because they were trying to raise money. Before that one was a teacher, one was an artist. And they were trying to get money to open a black school to teach kids about their own black culture and educate them about African things because no other, there was Jewish schools and other schools but they weren't any black schools and they wanted it. And everybody refused to give them the money to do it. Until this heavy African brother would just go, come on with this and stop going to the white man. Let's go the Spaghetti House and stick it up. They got money down there. And that's the real story, it really happened. And this is how they got into - luckily enough I was able to film it in the Spaghetti House. I used some of the guys who were trapped in the real thing as part of the film!

JA: But they agreed to do it...

HO: They gotta do it! Because don't forget this be talking about the 70s but 1961 or 62 I already lived in Italy so I was, they trusted me. You can't make us look like stupid Italians and you know, you must tell the truth. So this is what we did and it was banned because again the police didn't want us to show that they use guns to stop the siege because at that time the police didn't want admit to the public that they had guns. And they did this and it was, they tried to ban it at the BBC and the BBC was very good about it and argued that the film was honest about what had happened and blah, blah, blah and also the Italians said it. And then it was shown.

JA: I mean this political humanism - this is the last question and then I'm going to open it out and if nobody says anything I'll say some more... Political humanism - I'm happy to. I could talk all night, as you know! We've done this several times! The political humanism I'm talking about is also something that's reflected in your choice of stuff. There's always a shift on the drama, a bit of documentary...

HO: But this is real life!

JA: Let me ask you this question, because you keep saying this and nobody pins you down on it! You say and you know that some of us don't agree with this, but I now understand why you say it, which is 'Don't be put in this black bag' and put in a corner. Do you think that has something to do with why you work in so many different areas?

HO: Yes, yes, yes. Because I'm you know, because I love filmmaking. It's like, you know, my photography it looks like social political things about the black brother, but I photograph many other things, you know, that has nothing to do with what you're seeing out there. Because that's the world I live in, I live in the world and I love to travel, I love to study different things. And I don't want to be just limited just to make one type of movie, because you know, you are the darky filmmaker. So you just do that and shut up and then carry on. That was, that was never my scene. And still isn't. And I wouldn't encourage any black filmmaker just to accept. I'm not saying not to make black films, sorry. You're a filmmaker, forget every time to talk about you to talk to put your colour first. Forget that. That's bullshit. You know, you're a filmmaker, and you should get all the and be free to do what you want to do. And this has always been my attitude. But it's not that Horace is some clever guy. My parents gave me that function.

JA: You see, the interesting thing is, you know that in the conversation, there's a very interesting conversation between Horace and Menelik Shabaz, another very, very important filmmaker in the last issue of Sight and Sound, and you say, 'I don't want to be put in the bin'. And Menelik says 'Well, actually you see, I come to this because black was like a landscape that wasn't being painted. I wanted to paint it'. And yet when we look at your work, that's precisely what you've done.

HO: Yeah I did.

JA: Do you know what I mean. So do you think...

HO: Menelik was running about in that police scene...

[Laughter]

JA: I mean that's precisely what this is about. That was what Pressure was about, wasn't it. The demand to be free was then the demand to...

HO: It was the demand to be free and also to make a film about reality. It's all part of the real world, we weren't trying to deceive anybody, this is what's happening. This is what's going down. And a lot of films I mean, I'm not saying you shouldn't have your feature films and things, but a lot of films clean up and go the way they want to make, you know. Go down one road and don't say this and don't say that and take this off the scene and clean it up. What I tried to do with it is to show the reality that we were living in at the time and what was going on at every level. And there was the brave white girl that was able to attack her landlady and say don't, you know, for throwing her black boyfriend out and that happened! Those things did take place.

JA: I mean it was just extraordinary. You know, when we saw it, the first time I saw it, I was like, wow, this guy caught us. Because, of course, all the tensions and ambivalences, contradictions of that boy's life... So, did you know that? I mean Darcus Howe didn't understand that!

[Laughter]

He says he doesn't really understand that. You just fell instantly this kind of misunderstanding, this chasm between you but yet you managed to cross that. How did you do that?

HO: I think, it's the world I live in. That's it. That's all I can say. I'm a, I'm a person that you know. I live in that world of just people I don't care what is the colour, class or creed or whatever, they're my friends and, and if you want to be a racist, and you're that stupid and you're that dumb, and you want to carry on, then carry on. But that doesn't say I'm going to stop having white friends because one guy's a racist, or one guy's foolish. But you know, I love people. And I believe in filmmaking. If you're going to be making films or writing novels, you have to understand people from all races and classes, unless you're joking. And I don't think you just pick up about personalities and people just by reading a novel or something or getting an idea from that alone. You have to get to know people, you're gonna have to get to know them in real life, to really reproduce that whole thing.

JA: Let's stop there. So do you have any specific questions about Pressure?

EEJ: Hi, it's Ellen here with the first of my interruptions The question is about whether Ove shot any film with civil rights activists, Michael X?

HO: Michael X! Quite a character. Yes. I photographed him and I think I never really made a film on him. I mean we shot some bits and pieces. But I photographed him in various activities that were going on at the time. But to get into a story of Michael X... Heavy. Michael would critique you on every level of society, Michael - I'll give you an idea of what I'm saying there. All right, Michael could be on the block with all the hustlers, the drug dealers, I mean, white and black and heavy and everything on one scene. And two hours after, he'll say I have an appointment, and he's up somewhere else with Lady this and Lord so and so and. In that sense, and that was his kind of life. He moved that way. Michael X went to the head of the police station in Ladbroke Grove to tell him that racism got to stop and people have to to stop attacking black people in the street and treating them as... the police gonna do something and he arrived in a convertible - I think it was a Chev or something - with the police inspector's daughter in the car, waiting for him.

[Laughter]

Carry on from there.

JA: Anyone else? Okay...

EEJ: This question is, was there a director or auteur who had a big influence on the films you made?

HO: Well, I had a great influence by Antonioni and Fellini, you know, and Bunel and all those sort of... because I lived on the continent and I just, that whole new world on the continent really messed my head up because growing up in Trinidad, growing up in the Caribbean and just seeing American films and then go in and De Sica and all these works really changed my mind and realised that they made films, the surreal films that would deal with the realist world, and the world around you and the world inside of you and reality. So that changed my whole approach to filmmaking.

EEJ: This audience member asks a lot of your energy seems to have come from adversity. Do you see the same level of spirit from young black directors today?

HO: I know exactly what you're talking about. But I think what we had then is that whole togetherness through that black struggle and black power, that people came together and identified, and was trying to help each other, black people on all different levels, because of the racism they're facing, because they wanted to change things. So people became closer and closer together. You had that feeling. You know, and you could have, we did, I mean, that's why I made the film on Baldwin's Nigger. James Baldwin and Dick Gregory came here and allowed me to make a film of them for nothing and all that because that was the kind of togetherness and you had more of these political meetings and meeting places where you're talking about trying to work out the problem. So it brought that kind of community that I don't think exists, quite exists today with young black generation. You know, trying to help each other on all levels of society.

JA: There's also this tension between your interest in art or aesthetics and politics. And it's there in all the work. What do you think that's about to you?

HO: I was brought up with art around me. You know, my father was in the hardware business but he was a mad artist, right. In the house, he would change things, buy objects, put it over my house, you're falling over all kinds of objects that he's recreating and all that sort of thing. And then and then, my whole family was also involved in the carnival, where people were designing and painting and making costumes and thinking of the, you know, a new idea. So you're growing up, it's like an art school. You know, you growing up with that all the time as a kid. And also we had, and in those days we had theatre at home and each family home and friends in the area will put on a short play or a play and we'd all act in it, you know. So that whole environment was there before I arrived in Europe. So it messed my head up. It was there. It's always been there. And it's still here, because my whole world is painting, drawing, photography and film and I can't help it. You know, it doesn't make me rich, but I can't stop doing it.

JA: So did you have that kind of quintessentially, Caribbean, African thing here? Did the politics come when you arrived here?

HO: Oh no, the politics was long before I arrived, the politics as I was aware of it. That happened in Trinidad also. The politics and being aware of politics was happening in that part of the world. And because I grew up with a family and friends and people who was aware of politics there and abroad, you know, I mean, we had this strip in Trinidad, and I'm talking about the 1950s we call the Gaza Strip. We American soldiers with jeeps and cars and all that sort of thing, driving on the Gaza Strip. Because, you know, Churchill - I hate to tell you guys, Churchill gave them to the Americans for them to come into the war in the 40s. For 60 years, they give Trinidad to train soldiers and guerrilla warfare. So they came and they tried to take over the place. So you come over to your house and there's jeeps and cars like what you see in Vietnam films, that happened in my island. And they had this strip they called the Gaza Strip, where all these kinds of things had happened. The film that I still want to make, there was a big black guy called Samson. And every Saturday and Sunday, where all Americans were hanging out in the clubs and the bases, Samson will train and he's wrestling and he's fighting. Right? And he will go down there to challenge these soldiers who were outside the bars and clubs and people would bet. You know, you grow up with all of this, you've seen all this fighting going on. So coming out to Europe, which I've lived and travelling through, and Africa and everywhere else, you know, just put everything together...

JA: You know, somebody like Michael X, you knew him in Trinidad.

HO: I knew Michael in Trinidad as a young boy.

JA: And you knew him here?

HO: Yeah. Got to know him here.

JA: So the was there a difference in the kinds of ideas that you guys I'm talking politically?

HO: Yeah, quite different. He was in a whole different world. But when he got into the whole Black Power scene and what was happening and all the meetings and activities and demonstrations, you know, I took that opportunity to photograph most of it. Because it was there, you were conscious that this was the thing that had to be done to change things of what was happening to black people at the time.

JA: Was the desire then to make these images, I'm talking films, not photographs, was that coming from that world or somewhere else?

HO: No it was coming from that work!

EEJ: This question is about whether Ove would be interested in making a sequel to Pressure?

HO: It would be interesting to do Pressure Park Two. It will interest me to be involved in a project on it. But I don't know if I should be doing it though. I don't know if I'll be stepping into something where a younger generation who is going through... Like Pressure, I went through the experience, and I could still see what's happening around me, but maybe a younger person who is going through and living it, like I did in the old days, should do it themselves, you know.

EEJ: Next question, how did you come by lead actor Herbert Norville, and what made you choose him?

HO: I don't know. Most of those guys were not really real actors. Even the guys were playing the rough part and the guys who were stealing and robbing. They all came out of real life. And Tony, yeah, he was interacting and all that sort of thing, who had the lead and all that sort of thing, but he hadn't done a lot. Most of the other characters, young characters, I found them by when we were researching the film and was going all over the place, you know, and they did it and they played themselves. And a lot of the dialogue we'd written and when we were filming it, they put their own stuff into it, we left it - to keep that reality going, because I really wanted that. I really wanted to have, you know, real people playing the part.

EEJ: The next question is, what do you think has changed since you made Pressure? And do you think there is still radicalism in the current generation?

HO: Using the word radical, they're not as radical as before. I mean, you know, but I don't think they have to. Things were heavy in those days. Heavier. I mean, it was much tougher for black person out there. And I think it is what created the whole Black Power movement and how to be even more radical. But please don't forget also you had the 60s white generation that wanted to change also and they were radicals and they demanded change. So all these things came together. I don't know. I mean, I could still see that we have our a lot of problems going on at the moment. I don't know maybe Big Brother's taken over. Something happened. You accept it. You don't fight back, you don't demonstrate, you know, come on and say we don't want that.

EEJ: This audience member thinks that Pressure shows how the situation for black people in Britain has come on leaps and bounds since the 1970s.

HO: You know, it's a very good thing you're saying there, and you should go leaps and bounds. But at the same time, don't forget, old grandma and mother and the struggle the day when she - you don't have it now - and they had to go there and kick those gates open and open those doors and fight for those rights. And they did it because they faced a lot of brutality. And that's why you're right, and maybe things are easier for black women, but there's still racism existing. I find racism existing is the most primitive kind of thing. I don't know why we go on about racism - it's so stupid.

JA: Would you want to say something about Empire Road?

HO: Empire Road was a great series, and I was happy to work on it. Michael Abbensetts wrote it, and I came on and did a few of them and I enjoy doing it. I think it was the first sort of positive kind of black series done in the country. And a very good one. I don't know why the BBC put an end to it, but they did.

Can I just say something? Because there are two gentlemen, and I don't know if they are still here, one is David Rose and Peter Ansorge. I mean, it was these brave gentleman, who gave us the opportunity in television, both Channel 4 and the BBC - they are both white - to do the kind of films we wanted to make. And that was a brave act by these two gentlemen because a lot of people did not want to know.

[Applause]

JA: And what did you work with these two gentlemen on?

HO: A lot of stuff, a lot of stuff that we did. They're the ones who created Channel 4 before it's just gone to Big Brother [laughter] but they're the ones that did all the interesting programmes, all the drama and everything, not only with me with other directors and other people, and they created it, both for the BBC and Channel 4.

EEJ: This question is, you said you scripted the film before working on it, but wasn't a lot of it still improvised?

HO: Yeah, but improvisation was something that we always was open to, so although we scripted it, and we knew where the story was, we were ready for improvisation. And because we brought real people into it, too. I mean, you didn't take all the improvisation you'll say, wow, that's heavier than the script. That's brilliant. Let's go with this, do this. Keep it, don't cut that out. And that's how we went through with the whole thing. You know? Because they were bringing their own experiences.

EEJ: Now the final question, is black representation on screen in a stronger place now? And is it harder or easier for black people working in British film?

HO: Let's put it this way, a lot of black people are working on television and they're doing a lot of parts and things and they come and go in hospital series [laughter] and people are working. A lot of actors. But they're not telling... they don't have the opportunity to tell their own stories and make their own films and do it the way they want to do it and say what they want, you know. You know, it's just a job. So you just a doctor in something in something else, or a policeman in something else... where they would like you to be. I mean, I'm not putting it down. You know, everybody needs to work and things, but you still need the opportunity to tell your own story and do it the way you want to do it like any other filmmaker.

JA: Ladies and Gents, Horace Ove.

EEJ: Thanks for listening to this Barbican ScreenTalk with Horace Ove. Tell us what you thought on social media at Barbican Centre. And if you'd like to hear more, please subscribe to this podcast via iTunes or Acast.