Speakers:

EEJ: Ellen E Jones

AK: Asif Kapadia

JG: James Gay-Rees

MP: Manish Pandey

PH: Patrick Haze

EEJ: Hello, and welcome to this, the latest in our series of Barbican ScreenTalks. Every month we’re bringing you interviews with some of the world’s most influential filmmakers, hand-picked from the Barbican’s vast archives.

In recent ScreenTalks we’ve heard from the likes of rock star-turned movie composer Clint Mansell, dark and distinctive writer-director Carol Morley and Trinidad-born artist and film-maker Horace Ové.

In this episode we bring you a conversation with the man behind the two most financially successful British documentaries of all time. Hackney-born Asif Kapadia started out as the director of critically-lauded art films such as The Warrior and Far North. His career really went into overdrive in 2010, when he turned his hand to documentary film-making with Senna.

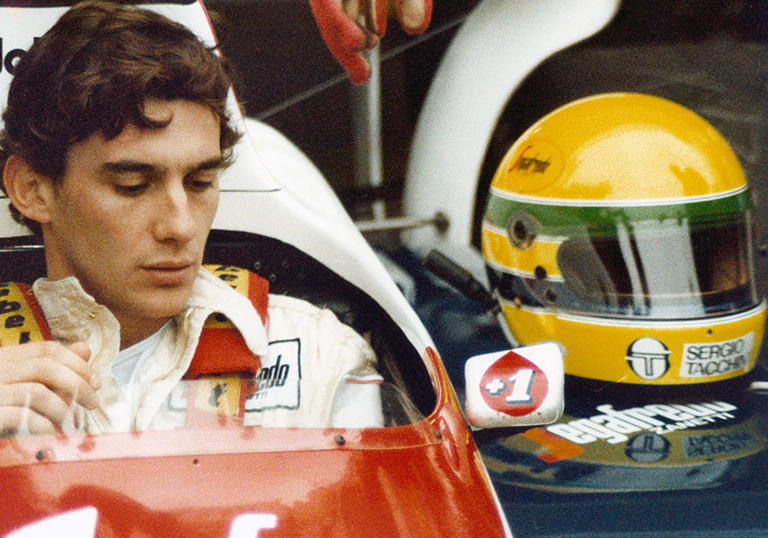

Focusing on the life and death of Brazilian Formula 1 legend Ayrton Senna, Kapadia’s remarkable biopic managed to break entirely new ground. Not only was it a documentary that proved extremely lucrative at the box office - it was also a sports film that even the most sport-averse could enjoy.

The film covers ten years in Senna’s career - from his debut in Brazil in 1984 to his death at the San Marino Grand Prix ten years later - it consists almost entirely of archive footage, Senna avoided standard documentary techniques, in favour of a far more cinematic approach.

Kapadia followed the film with the even more successful Amy, this time examining the tragically short life of powerhouse singer, Amy Winehouse.

But in the interview you’re about to hear, Asif Kapadia is joined by producer James Gay-Rees and writer and executive producer Manish Pandey to talk about Senna.

Speaking to Patrick Haze, as part of the London International Documentary Festival in 2011, the trio discuss how they managed to wrangle weeks of incredible footage into just over one hundred minutes. They reveal how they persuaded F1 magnate Bernie Ecclestone to allow them access to his personal archives. And they debate the timeless, magnetic appeal of Ayrton Senna himself.

Some of the questions in this recording are difficult to hear, so I'll be back later on to help out with those.

But for now, I’m Ellen E Jones and this is Barbican ScreenTalks, with the makers of Senna.

[Applause]

PH: Well, I'm joined on stage here by Asif Kapadia, the director, and Manish Pandy who is the writer and also producer and James Gay-Rees who is the other producer. So I'm not going to speak for very long, I'm going to get straight to the point more or less, I was reading a piece about portraits and portrait films, of which we're featuring quite a few, and there's a line that says, these portrait films or profile films often tell us as much about the director as about the subject. So, we've seen the kind of global impact of Senna, but we might as well go back and ask Asif, what this tells us about him, really.

AK: I don't know...! That's a good... It tells me that I'm not a documentary director

PH: That's the first revelation!

AK: I'm a drama director so a lot of the way the film was constructed was done in a way that I suppose I'd do a drama. I didn't start with talking heads, I didn't start with, there was no intention to have a voice over or a narrator. The idea was quite early on, as we were working together, and with the editors, to try and find a way to make the film where Ayrton was the narrator of his own life story. So I suppose some of the kind of convention of how a portrait film would be done, which would be, go and interview the people, we'd kind of do that last. We actually started with the material. And obviously there's one key person we couldn't interview which is Senna. And so what we didn't want to do was make a film of everyone else's opinions of him. We wanted to make his opinions. And that was a key part of it. I suppose also, it says about me that I like cinema and I like sport, so it was kind of a coming together of two passions for the first time. Yeah, I don't know, you'd have to tell me what it said!

PH: Obviously the film itself, the life story has a particularly dramatic arc, but, if one chooses to take on the huge task of kind of representing an individual's life, there has to be some core value or motivation that is governing that choice. Because of all the subject matters that are out there, this is the one that you chose.

AK: OK. This is interesting because conventionally, if I were doing a drama, I'd be writing and I'd be directing and I'd be the person who'd initiate the project because this is a question really for those two because they... James had the initial idea to make the film and he can explain better than I can why. And then we can kind of follow it through, because I came on to it last.

JG: Well, the genesis of this is basically due to the fact that my father was the account director for John Players Special Cigarettes. Which, as you can tell from this film, most of the cast look like cigarette packets. They all wander around looking cigarette packets, it's kind of really crass in retrospect to look at that footage. But, he was the account director when they sponsored the Lotus team, so he would go to the Grand Prix after various events and do the kind of sales campaign. And he came back after one campaign saying there's this young Brazilian kid, who is just so incredibly other, he's so intense, he's so otherworldly, I can't get it out of my head, basically. And sure enough, a lot of the Formula 1 population quickly came to the same conclusion that he was very special this guy. And it developed, and it developed and he became, you know, the rising star, as it were. And I kind of, never really followed the sport to be honest with you, that much but what my father told me about this guy did stay with me. And it wasn't until much later, when I was living in Los Angeles that I realised that he had, I was living in LA when he died basically. And I remember my Dad ringing me up and saying, 'Have you seen the news? Senna's dead'. And I was shocked, he was shocked, you know, I just can't get my head around that. I can't believe he's died. I can't believe he made a mistake. And so, he just sort of lodged in my mind as a very special character from a very early stage. I had this kind of silly analogy that basically, I've always felt that you could be at any situation anywhere in London, or any city for that matter, having dinner with a bunch of people and you know, one of those people at that meal would always go, 'Oh my god, I love Senna'. And for some reason, this guy transcended sport. He was so magnetic and charismatic in the way that icons tend to be. And so the genesis of the movie really was trying to explain why this guy had such an impact on so many people. Above and beyond the fact that he was a brilliant racing driver, he just had x-factor in abundance. And I was very fortunate, very early on in the proceedings, to meet my friendly colleague, Manish, here. Who is an absolute F1 and Senna fanatic. And he put the vast majority of the meat on the bones of the subject for me which ended up being kind of the road map for this movie. And at this point, I'm going to hand it over to him.

MP: I think of the three of us, as James has said, I was really the Senna fan. And for me, as a teenager, he was that sort of perfect blend of genius, outsider, the guy who came from the third world country and taught Europeans how to do it - and taught Europeans how to do it better. And Formula 1 is a very English sport. And the mechanics, I always think they represent football fans, if you like, and this was a sort of god amongst football fans. I think the thing that really got me about him was, it's a word that James didn't use today but always used to use, which was there's always something about him that was otherworldly. I remember in 1985, Murray Walker describing Senna, just at the beginning of the Formula 1 season, I saw him just looking at his Lotus and in the way that drivers just don't. There's an intensity to it. And he said if there's a young man that can become world champion in his first year driving a Grand Prix car, you're looking at him. And I think that absolute intensity, that absolute passion and that completely dogged spirit - he never, never gave up. And he always had, in a way, one answer to all of life's problems and that was just to drive. And to drive faster and to drive better. And that's why I find the end of that film, I always find it very distressing because you see him in the middle of the film with a crumpled driver and his response is to get in the card and go even faster. But right at the end of the film, when Ratzenberger is killed, it's the first time you see Senna in civilian clothes in a garage. And I think there was great angst in his mind that night. And I think he would always choose to drive and do his duty, but that's what I always loved about him. You know, his solutions to very very complicated problems was just to do. Or just to drive.

JG: I think there's another aspect to that, though you're right, that there is that kind of impulse to overcome and drive and go faster. But there is this issue of dealing with very real world problems. He wasn't divorced from reality, he might have been this figure who seemed otherworldly and so on, but the work of the foundation in particular is an example of how embedded in the real, material world of Brazil.

MP: The thing about the foundation was it was set up after his death. Interestingly, what he would do, is he would get a charitable request and we actually met a very good childhood friend of his, somebody he absolutely trusted. And what he would do is he would get this guy to investigate to go and see whether it was real or not. And if it was real, he wouldn't just donate but he would keep the donation going. You make a really, really good point there, that this isn't some sort of airy fairy character either. Formula 1 is highly technical. I mean they sit and pore over the data for hours and hours and hours and he was the most technical of the lot. And if I had to guess his IQ, he probably has an IQ of about 150, I mean you are looking at a guy who was an intellectual genius as well. No doubt about it.

PH: Many people here I believe are not followers of Formula 1, I'm certainly not particularly, but I do remember when he was killed. And I do remember feeling quite shocked by it. And this film made me reflect on precisely that, what was it that made me feel shocked by this particular event? I imagine, many people here are perhaps in the same boat, and their curiosity about this person is not fueled - excuse the pun - by an interest in Formula 1. Before we come to you, I just want to deal with one last issue, where did you get the access to all this footage? Some of it is obviously family stuff and a lot of it is kind of insider material and I wonder how a lot of that came your way?

JG: We were very fortunate that we managed to persuade Mr Ecclestone to allow us entry into his archive. And we were the first people to ever get in there. He's got this kind of huge aircraft hangar down in Beacon Hill with footage of every race since his tenure in Formula 1. And we spent a long time going through that, we spent a long time going through all the Brazilian archives, for TV stations, Australia, Japan, Italy, France, Spain, Germany, the UK broadcasters. I mean, a mountain of archive. Our researcher is here today, Paul Bell, who did an unbelievable job of corralling the whole thing.

[Applause]

JG: He had the worst job in the whole film, there's no doubt about it anyway. We had it easy compared to him and he put a load of filters in place and went through everything with his brilliant people. Florence de Bonnaventure is here tonight, another one of our researchers which is fantastic. And, a vast amount of material anyway, and we collected it, looked at it and tried to shape the narrative accordingly. Always hoping we'd find little nuggets to enhance the narrative along the way. I should really hand over to the director at this point in terms of how the script was f ashioned from that material.

AK: It was an interesting process because, certain agreements were in place but we didn't actually have the paperwork done or things like that. So there was a whole thing where we were like 'Yes, we can go ahead and make the film' but actually we can't afford to pay anyone yet. So we were able to start the film, we had an edit suite in Soho but we couldn't afford to hire an editor yet. Paul was on board and Manish and I started off by putting together a short film, taken from footage from YouTube and footage from Manish's shelf. We had some Formula 1 end of year tapes. And I think it was about a 12 minute short film that we made which was just for figure it out, but also show other people how this film could work without talking head interviews. And that was kind of the beginning of it because actually like 95% of that short is in the film. All the kind of key beats, beginning, middle and end were there. Then, we just started to get whatever came through.

We'd all be sitting there looking on YouTube and following kind of leads to different parts of the world and saying 'what about this?' And then, illegally I guess, download it. Load it on to the Avid, cut it together and the first cut we had was 7 hours long. And then we had a 5 hour cut and then we had a 3 hour cut. And then right the way through there was this thing where at some point we thought, we're going to need interviews, but we kept looking at the material and it just worked, there was something there. There's something about him, and his stardom and how famous he was in Brazil before he got to Formula 1. He then became very very famous and loved in Japan at a time when there were lots of small portable cameras everyone. His family were wealthy so they had a home movie camera. The sport exists for television. So there's something about him, and something about the sport which he became famous in, and also the particular point of time - this is before Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, before PR. So people said what they thought on camera. And there's no body saying 'No he didn't say that. You didn't hear that. That's off the record'. It was like, everything was on the record. It's just that he'd be saying it in Sau Paulo in Portuguese and Prost would be saying it in France in French. And we were able to access all of this material and just have the two guys talking to each other.

A key decision was we didn't want to make a film now, where everyone looks back and said 'He was great, he was the best, we loved each other, we were great friends'. They weren't. You know? These are kind of sporting rivals who were at the absolute peak of their career who, you know, you do whatever you've got to do to win. And that's much more dramatic and powerful and emotional. And you know, just to kind of sum up his life and his journey, because not only did he live pretty much all of his life on camera but tragically his death was also on camera so, it was all there. We saw it quite early on and our biggest challenge over two and half years of cutting was, how to make, you know, bring it down to 90 minutes. Which was what our budget was originally. And eventually we squeezed out 100 minutes. One key thing is, when I did come on to the project it was originally set up as a slightly more conventional documentary. It had budgeted for 40 minutes of archive, 40 minutes of talking heads and 10 minutes of miscellaneous. And of course our entire cut was always archive so we couldn't afford to do it. So our producers had to go back and try and work out a way to pay for the film. We were cutting a film that everyone liked and people laughed in the right places and people cried in the right places but we just couldn't afford to make. And we were projecting YouTube to Universal, which you know, the film before us and after us probably cost £100 million then we walk in there with a tape full of YouTube. But it was believable. That was the key thing. It was all real, it was all true. What we were showing was real. And they were spending 10 million quid trying to make something look fast. When actually ours is much more believable and it looks like it cost nothing.

JG: We just had that job of going back to someone like Bernie Ecclestone and saying, 'Please sir, can we have some more?' then 'Please sir can we have double?' and 'Please sir, I know the contract said that everything over 40 minutes reaches a particular cost but we don't have that money what we've got is exactly what we've got for the first 40 again.' And to be honest, I think Bernie wanted this film made. Because that could have been an awful war. But you know, he said yes. And he said yes very quickly, didn't he? I think we got the yes within 3 days. And also, just the point that Asif is making, to make a feature film you need coverage. And you need to see that coverage, you can't send them a shopping list of things that you need before you've seen them. We had that conversation with this media rights lawyers and said, 'Look, we need to go in, we need to see what you've got' and they said 'Well, alright, you can come in for two days'. And we said, we need to come in for four weeks. And they said no one has ever been in there before. And we said 'We really need to be in here for four weeks'. And we had four weeks of access, three weeks of which Asif, myself and two other people used and then Paul went in for the remaining week and literally picked every single shot that you're seeing, timecoded, with I don't know what kind of patience. It was amazing.

PH: Alright, so we'll start with that hand up there

Q1: This question is about whether extra archive material would be included on the DVD release of Senna.

JG: There are, actually you know what is really good about the DVD and the Blu Ray, is that we do actually do a traditional version of the movie, which is about two and a half hours long but we cut in the majority of the interviews, so you see talking heads as you don't obviously see it in this version. In terms of the nuggets of Formula 1 footage that we couldn't get in the film... I mean, there's some amazing stuff that we couldn't put in the film for editorial reasons, we couldn't put it on the DVD. We may put it on a special edition at some point in the future but the two and a half hour BluRay / DVD version is really worth seeing, it's really good.

The hardest thing about this movie, as Asif highlighted, was the fact that we would have loved to have made a five hour movie, we could easily have done that. We could have made a three hour movie about Imola, we could have made a three hour movie about Brazil '91. I mean, it's such a wealth of material, but obviously convention dictates you have to try and get it into 90, 100 minutes and you know, so choices have to be made. But, there is a lot of material out there to make a sequel with...

PH: Is there anyone else with a question...? Yeah, right at the front here

Q2: Why was now the right time to make a film about Senna, and how did you decide it should be a documentary rather than drama?

JG: Well, after my father's sort of vague relationship with him, on the tenth anniversary of his death in 2004, I was actually down in Devon, of all places, and The Times ran a retrospective for a week about Ayrton Senna in the newspaper. Simon Barnes is a great journalist and a friend of the project, he wrote some really compelling articles about the otherness of Senna. As in, you waited all day to interview this guy and when you finally met the guy, all your gripes about waiting so long were automatically dispelled by the sheer charisma you were basically witnessing. And so, that kind of got my mind going as to why has nobody made this movie before? So I did a bit of research, I heard about the Banderas project, amongst others, and then quickly realised after some initial conversations with the Senna Foundation, that they had some misgivings about a kind of fictional narrative about his death because it would have to tick all the regular boxes. You know, there would have to be the baddie, the love interest. The kind of, you know, you'd have to box it up basically. So the idea quickly became to make a feature documentary. And I know Taylor Hackford vaguely, who made When We Were Kings, and that was a, the whole feature documentary thing was gaining traction at that point in time. But these things they take years, I mean, you know, we've been working on this for six or seven years. So, there's no one moment in time when it happens, you know. You've spent years trying to convince people, whether they're Eric Fellner or Working Title Universal, to finally make the movie, or Bernie Ecclestone. And then eventually they say yes. And then the last year and a half or two years is the mad scramble.

MP: James and I met on this in October 2004. And as he said, I think actually, weirdly, Eric at Working Title, I mean, he was already sold on James' idea and James said to Eric, 'I want to do a feature doc on Senna'. And he said, that's fine. And I think my early contribution, rather than doing something about the death about Ayrton Senna, we should do something about the life and death of Ayrton Senna, because that's how you get the context of the man. You know, it was an idea way back in November 2004. Every year, there was just another layer on this. And then finally it came together exactly a year ago, didn't it? We did our final cut, I think it was May 10th, exactly 2010, because we were in Cannes this time last year showing the final cut to the family.

Q3: How did Brazilian audiences respond to seeing their idol on screen?

JG: It's a hard thing for Brazilians to watch, because the country was in a very different state. And I'm no expert on Brazil but I've been there quite a lot recently, but, as you can tell from the film, the country was clearly in a much different state at that point in time. Compared to the thriving economic and social place it is now. So when they watch the movie, I think they'll be reminded of a time which is much harsher. And they don't necessarily want to go back to that moment in time. Because they have so much to look forward to now. But I think he was a great hero for them. They're glad a decent movie has been made for them about their hero but, it's sad nonetheless. PH: I think we've got time for one more question, if there's anyone who has...? Yes

Q4: I've found the best part of the film was actually watching Senna race in Monaco and just watching how close they were to the sides. Everyone goes on about it. I was quite interested in what your favourite parts - obviously you've gone through a lot of footage - but what your favourite parts were to the film, were they the interviews or whatever?

JG: That's my favourite clip, the one you're talking about, I think it's amazing. Just how fast he's going!

Q4: I kinda want to watch Formula 1 on a screen like this now! It'd be quite nice.

JG: I think Formula 1 might start doing it actually!

AK: My favourite bit is actually Brazil, when he wins in Brazil for the first time. That moment when he finishes the race and can't lift up the trophy and when his Dad hugs him and he says 'Touch me gently'. And then, everyone else 'Don't touch me!' I have to admit that makes my cry. That's the bit where, interestingly enough, technically, that's some of the weakest footage in the entire film, OK. Particularly when he's driving and what I like about it in many ways is also, it's the one... That sequence for me sums up Ayrton Senna up, OK. We never really show another car. He's racing himself. You know, he's winning and he refuses to quit. I'm going to win this race, I'm going to win it for all of Brazil, I'm going to win it for Sau Paulo. And he won't give up. And that is, again summed up by lifting up the trophy on the podium. And it's something to do with what he's doing, the way the crowd is reacting, the way the music works. I just love that sequence.

That's the moment I also think about...I would never have been able to do that if I was making a drama. Because what are the changes, when OK, I have a shot on my script of a man lifting a trophy. And I need 40,000 people there, a helicopter, and about 30 other cameras to cut that sequence - it's not going to happen. You've got 15 minutes, you've got 35 people just move them around a bit, is normally what would happen in a drama. And I just think that sequence is my favourite, and technically it's one of the weakest of that driving footage. But it's him, kind of doing the impossible, driving a racing car in sixth gear. So I really love that bit. That theme, that theme, Antonio Pinto, the composer, he did City of God, he did Central Station, he did Collateral. And Antonio, his agent contacted James, something about Senna, something about this film, we've had people ringing us up from around the world saying, how can we help? I hear you're making this film, how can we help? I wanna do it, I wanna do it.

So, Antonio was in Sau Paulo, we were editing in London and we didn't actually get to meet. So, I said to him, look, I'm going to need to get this worked out somehow. Can you write some music while I'm cutting, because I'm cutting here in London. And I don't like temp scores. So he went away and wrote three themes. And that theme you hear at that point was something that he wrote before he saw any of the film - it was just from his heart. It's his memories of Senna, and what Senna meant to him. And that's like the main theme you hear at that point but also at the end of the film. Antonio was a major part of the film. Of course, we haven't mentioned the editors, Gregers Sall and Chris King. The sound guys as well, because one thing we have to say, we couldn't recreate anything. We can't just go and get a Formula 1 car and then drive it to pick up some sound.

You know, those cars don't get driven, and definitely didn't get driven like that, so every element we had to construct using whatever we could find that was the real materials from the sound to the pictures. And just another thing to mention regarding the researchers and how the film was constructed was that very often, you know, we've got a shot that someone's found in Paris, cut with a shot that comes from Japan, cut from a shot that came from Globo in Brazil - to put them together to make it work like a match cut so it feels like it's all flowing from one camera was a big technical part of what we were trying to achieve.

PH: Well, I'm afraid at this point, we do have to wrap up. I just want to say, first of all, thank you to Asif, Manish and James for being here. But also for all the members of the production team who are in the audience and of course to you for being here tonight. Thank you very much. [applause]

AK: Thank you

EEJ: Thanks for listening to this Barbican ScreenTalk with the filmmakers behind Senna.