For nearly six years, Transpose – a cross-genre event showcasing trans and queer artists – has focused on film, spoken word, classical music, poetry, comedy, and visual art. But it was only after our first show with the Barbican in 2016 that we realized that we’d never really thought about the theatre of it all: what happens when a trans person takes the stage, and what magic that space allows.

A strange oversight? Maybe. Some of our most visible and enduring cultural moments of gender subversion and queer desire materialize in front of an audience. Drag stars, pantomime dames, Shakespearean boys, and mezzos in trousers making love to the soprano. Costume, make-up, and that carnival atmosphere where ordinary rules of behaviour and identity are suspended.

We have the chance to share lives too often derided or seen as too complicated to understand

But in our day-to-day lives we suffer from this association. Most, if not all, trans people will know the pain of being called a fake and a pretense. Worse than fakes: deliberate deceptions. If how we present ourselves is accepted as truthful in the dark of a theatre, it’s too often derided as trickery in the light of everyday experience. People want to know what’s underneath, before, ‘original’, as though who we are is a costume they have the right to remove.

And yet there is still something intensely powerful about this association – something deep in our history as gender outsiders. Sometimes that history is one of private performance: the mollies of 18th century Europe – a unique gendered category of the time – performed secret staged rituals of marriage and childbirth. There are cases of odd mirroring: Victorian music halls, with their drag comedy acts and principal boys, were also home to cross-dressed sex workers plying their trade. Most meaningful of all are those points where exploration on the stage went hand in hand with increased personal and political freedom. Weimar Berlin was broadly famous for its cabaret scene, but those cabarets functioned not just as entertainment, but as meeting places and community centres for a trans population newly recognized and fighting for their right to exist and thrive.

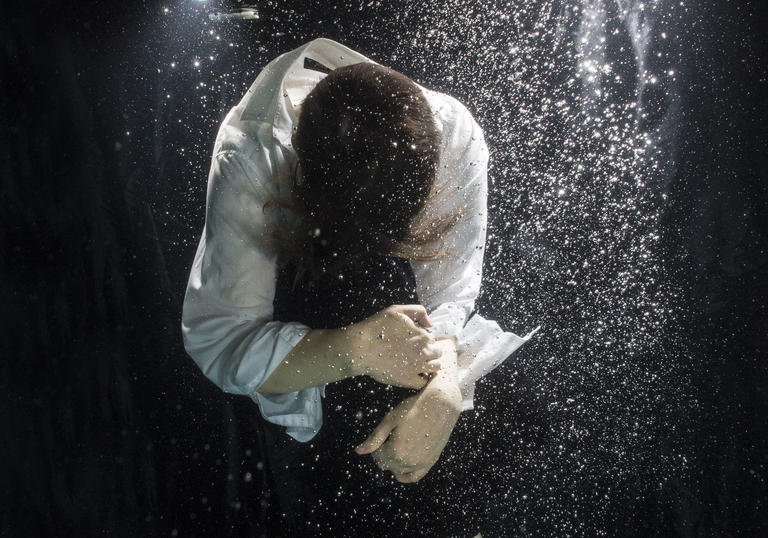

Michel Poizat, writing on the ecstatic power of opera, described the ability of the human voice, in a darkened concert hall, to strip an audience of their identity. In that moment – safe in anonymity, overwhelmed with pleasure – we are transformed beyond our sense of self: age, nationality, mode of living. Crucially, we are transported outside of our accustomed genders and desires.

When trans people take to the stage we take with us, by necessity, all the good and the bad that comes under our experiences of performance, performativity, and fantasy. But the most extraordinary thing is that we have the power to take the audience there with us. The power shifts. Empathy shifts. In that combination of experiences, we have the chance to share lives too often derided or seen as too complicated to understand. As an artist, theatre is always a magical space for me. But as a human being, that exchange is the most precious.