In 1945, Jean Dubuffet draws ‘Pisseurs aux mur’. At the forefront are two men urinating on a towering wall. A wall whose tiny motifs tell a quaint story of 1945 Paris: the year, ‘Merde’, and a declaration of love from Lucienne to Emile. An urban weird and wild energy.

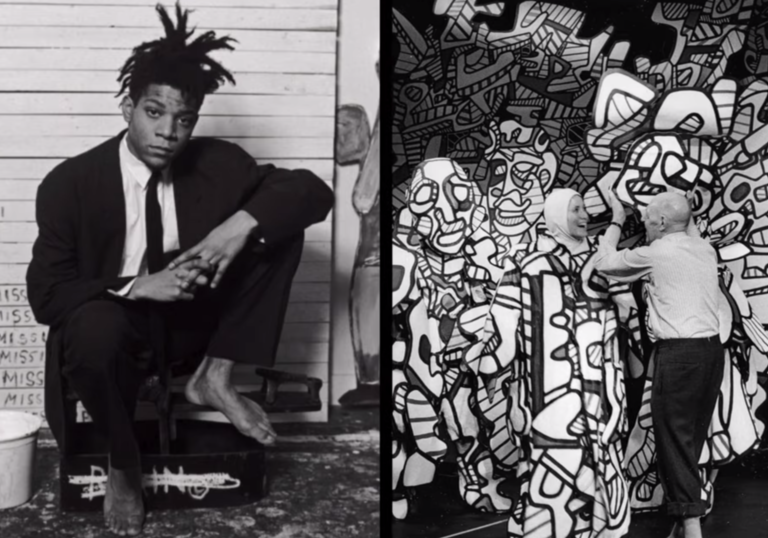

Fast forward thirty years to 1978 New York. A city convulsed by violent crime and on the brink of financial ruin. There, Jean-Michel Basquiat (a teenage artist) has just moved from Brooklyn to Manhattan.

For his first major exhibition, New York / New Wave, Basquiat used found trash from around his urban environment – perhaps, scrap metal; foam mattress; or chipboard – as the support for 26 new works which jostle with the noise of Manhattan life where letters cascade over scrawled cars, airplanes, and skyscrapers.

The critics immediately saw a parallel to Dubuffet’s career, presumably thinking of his bustling Métro series, or the cartoonish cars in his ‘Paris Circus’ works.

And in Artforum, December 1981, the provocative poet Rene Ricard wrote a piece – "The Radiant Child" – about Basquiat. He commented:

"If Cy Twombly and Jean Dubuffet had a baby and gave it up for adoption, it would be Jean-Michel. The elegance of Twombly is there… and so is the brut of the young Dubuffet."

The critics were onto something.

Firstly, both Dubuffet and Basquiat shared quite an anti-authoritarian spirit. They set out to dismantle what had gone before: the polite easel painting of Beaux-Arts Paris and the cool Minimalism that reigned in New York.

And neither one chose to pursue a formal art education, either.

Both Dubuffet and Basquiat were each drawn to self-taught artists. Dubuffet collecting what he called ‘Art Brut’, including work by children, spiritualists and psychiatric patients.

They also produced their work similarly, too, at times painting with their canvases positioned directly on the studio floor.

But perhaps most importantly, is that each were invested in the idea of truth beyond resemblance. The idea that while a work of art could be perfectly 'accurate' and realistic, it may in no way capture spirit. In other words, works could ring with truth and electricity through doodles and representations that appear to the eyes as anything but real. They did this by looking for modes of painting that would give a work the impression of life, as if it'd had a pulse of its own, which is not such an easy thing to do.

Strangely, when once asked, Basquiat denied any knowledge of Dubuffet at all. Now, Jean-Michel may have simply been uninterested in indulging in that question, but taking his words as truth, perhaps he adopted Dubuffet inspiration by way of Cy Twombly, instead. Once when flipping through Life Magazine, Twombly found a Dubuffet piece, ripped it out, and from then would paint with it kept in his studio.

However it came, by the mid-1980s, Basquiat was not only familiar with Dubuffet’s work, he was an avid admirer: he asked the founder of Pace Gallery, Arne Glimcher, if he might be allowed to visit the gallery when they were installing Dubuffet exhibitions so that he could just sit with the work for a few hours.

More direct allusions began to appear in Basquiat’s painting – such as the perilously high horizon line of King Zulu (1986) and Pegasus (1987), a motif borrowed from Dubuffet’s 1950s landscapes.

A monochromatic ‘paysage’ from 1952 was once exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art in 1987 and Basquiat may have used it as a direct reference point when creating Pegasus. With all they have in common, the world may never know if the two artists ever met.

But they did exhibit side-by-side on at least one occasion during their lifetimes in Expressive Painting After Picasso at the Beyeler Foundation in Basel in 1983, which also featured the work of Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Joan Miró.

Basquiat was only 22, while Dubuffet was a stately 82. That their work could stand up alongside one another’s, despite a 60-year age gap, is a testament to the former’s prodigious talents and the latter’s relentless invention.

Today, someone is just as likely to learn about Dubuffet via Basquiat as vice versa, which feels a truer reflection of their relationship: not as artistic parent and child, but as intellectual companions, who wanted to capture the chaos of the mind and both believed in the alchemical power of painting to do so.