Speakers:

EEJ: Ellen E Jones

BRR: B. Ruby Rich

MA: Michelle Aaron

EEJ: Hello, and welcome to Barbican ScreenTalks, where each month we delve into the archives to bring you conversations with some of the most prominent figures in cinema.

Previous ScreenTalks have included Ken Loach, Carol Morley and Park ChanWook, all recorded right here at the Barbican and available to download now. But this month’s conversational gem didn’t involve too deep a delve. It was recorded earlier in 2017, at the opening night of our Being Ruby Rich film festival, celebrating the work of New Queer Cinema champion, feminist film critic, educator and agitator, B. Ruby Rich.

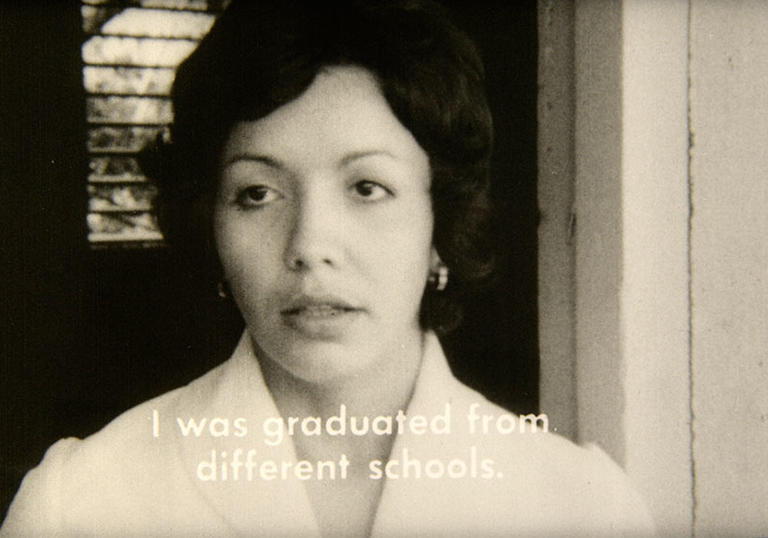

In the recording you’re about to hear, we start with Rich delivering a keynote speech - introducing both the festival and a screening of director Sara Gómez’s 1974 film De Cierta Manera. Then we return to listen in to the lively Q&A discussion that followed, featuring Rich in conversation with interviewer Michelle Aaron.

In her time, Sara Gómez was involved in exactly the kind of 'new forms of address and rhetoric' that B. Ruby Rich calls for in her keynote speech here, so the screening of De Cierta Manera makes perfect sense. As the debut feature of Cuba’s first female director, it combines Rich’s interests in Latin-American cinema, feminism and the possibilities of documentary.

In the film, Gómez uses both documentary and drama to depict a romance between Yolanda, a bourgeois teacher, and Mario, a factory worker. As Rich explains, its study of the interplay of race, class and gender means it is an early example of intersectionality on film - made before that now fashionable term had even been coined.

Discussing the first time she saw the film in Cuba, Rich sheds some light on Gómez’s identity, her practice of the Catholic Yoruba religion of Santeria, and the circumstances of her tragic death just a few months after the film’s shoot was completed.

De Cierta Manera also provides a jumping off point for Rich to discuss her developing thoughts on Queer representation in cinema, to explore how online viewing platforms are changing film, and to reflect on the continuing influence of her book, Chick Flicks: Theories and Memories of the Feminist Film Movement.

Have a notebook and pen to hand, because you’re about to hear some viewing recommendations you’ll certainly want to follow up...

And now, in deference to Rich’s call for a new Cinema of Urgency, let’s get stuck in.

I’m Ellen E Jones and this is Barbican ScreenTalks, with B. Ruby Rich.

BRR: It's really wonderful to be here and thanks to all of you for being here, in such fraught times. Yesterday at Birkbeck where some of us were with students and with each other in a symposium, Lara Mulvey gave me this key, I don't think it's just a key to my work, I think it might horrifically be a key to my life - when she said that she finally figured out that our differences back in the old days had to do with my impatience. That theory was just too slow for me. And that she now realises that my work is characterized by an impatience with what's going on and this attempt to kind of, move it forward. And I think that's still true. I'm not sure if that's good or bad. But I guess I'm stuck with it. It's been rather consistent. So in keeping with that notion, I had already titled this 'A Cinema of Urgency', so thus proving your point, Lara. But 'A Cinema of Urgency' for rapacious times, and I think it's a word that might need reviving. I don't think we're just in avaricious times, I don't think we're just in intolerable times, I think we're really in a time of rapaciousness. With all of its meanings. And that we need a cinema, a film practice, a video practice, a visual representational practice, that goes beyond what we used to ask for. That goes beyond a demand for recognition. That goes beyond a space of opposition. And what might that mean, what might a 'cinema of urgency' mean. So, it's a strange time, here in London. When we first began discussing this, it was a pre-Brexit moment in the world, the American presidential election hadn't happened yet, that the current state of things was unimaginable, and those glory days before November. And, we conceived this in those days. So there's a kind of bizarre time travel involved in arriving here now in this changed world. And of course arriving here in the wake of the Grenfell Tower fire, which is just barely more than a week ago.

What does this have to do with cinema, though? With your reason and mine for being here, this evening in mid-summer. I think it's a measure of urgency. And I have different urgencies I want to go through and one of them is, we must be enabled to see each other once again. I think part of the tragedy exposed by Grenfell Tower is that people who make policies today in our countries, do not know the people whose lives are affected by those policies. They have no idea. And I think more generally, people do not know each other once again. And that we need cinema to once again rise to that age-old function, of introducing us to each other. And leaping over those chasms because they really are truly chasms in these segregated spaces, these bifurcated spaces. Where does the camera go, where does it not go? Who can be seen? Who gets to look? Who gets to speak? And I was struck by a film that I used to use in teaching, a little, a little film by John Grierson called Housing Problems, 1935, in which they are optimistically talking about how all these problems with the slums is going to be solved by these new housing blocks that are going to be put up. Which of course then either get demolished or turn in to what exists today. And his sister, who I am always very fond of and wrote briefly about in 'Chick Flicks', named Ruby Grierson, was adamantly against John Grierson's way of looking at people. And she said, you know, you're a problem, John. You look at people as if they are in a goldfish bowl. And he was very amenable and said, yes, yes, of course, what's wrong with that? And she said, well I'm going to smash your goldfish bowl. And he allowed her to do that. She was the reason the microphone got handed to the tenants in Housing Problems, to speak directly about their own lives, without someone else simply drawing a line about them.

And so I'm reminded also of the iterations, more recently of work about people living in these kinds of housings, these forms of housings, whether it's Andrea Dunbar and Chloe Bernard, wonderful The Arbour, 7 years ago, or Andrea Luka Zimmerman's Estate: A Reverie, just 2 years ago about the end of the Haggerston Estate. Or in a fictional mode, even Lynne Ramsey's Ratcatcher, about Glasgow during the garbage strike and how one navigates that environment and those streets. And then the work of Eduardo Coutinho, the Brazilian documentary filmmaker, and not a woman, not queer, but incredibly important, who I spent an issue of Film Quarterly, which I now edit, dedicated to, who went out beyond the Griersonian model, to speak to people, and invented a mode of documentary that he called a 'cinema of listening'. And that others have called a 'cinema of conversation'. And the piece that he made, Edificio Master, shot in one housing block in a poor neighbourhood in Rio, but it's not just about what we get to see, or who makes it but how we get to see and where. So the proliferation of these new platforms, how they're changing documentary, how they're changing it for all of us, queer filmmakers, feminist filmmakers, every filmmaker of every kind, how the frame is being expanded, how the platforms are multiplying. And yet, as we know, reinforcing the same old parameters, the same old walls. The same old exclusions.

And yet for a minute, there's always a space for contradiction, where there's an opening, that could emerge in these moments of transition. And so, in Latin America now, in Brazil and Argentina, people are making something called 'ninja cinema'. And why is it a ninja cinema? Because it can only be seen live. It's only shown live. So that therefore it can't be censored because no one knows it exists until it's happening. So people are broadcasting, so to speak, from demonstrations, from events, from performances on Facebook Live. Notoriously used in the case of Philando Castle, whose police killer just got exonerated. Using Periscope, using different kinds of modes to reach different kinds of audiences and a new kind of prop. Whether it's something like Chalk Girl, that popped up recently on The Guardian Shorts page, or whether it's the op-docs that pop up on the New York Times, or the AJ+ shorts that use text on screen so you don't have to have the sound on to even understand what's going on. Or the new platform that Lara Poitras has created called, Field of Vision, short pieces talking about urgent issues. But the urgency cannot be only, only in these kinds of forms. It has to extend across the whole range of media, up and down the status ladder, up and down the spaces that can be mobilised.

But for documentary, before I leave that, I just want to make a plea to move on from the notion of storytelling, which has overwhelmed and overtaken everyone's idea of documentary. 'I'm telling stories' - that's very nice. But what happened to investigations? What happened to exposes? What happened to looking under the rock to see what's hiding there? In this, so-called 'post-factual' moment, we need that desperately. But we also need, and this is my next urgency, we need new forms of address, we need new rhetoric. And I think this is an area where film and video, inside the Academy and inside the movie theatres, have fallen behind. Now, we don't know how to reach generations trained online, we don't know how to reach members of the public shaped by the post-factual era, shaped by the rumours and the lies. Why did people vote for Brexit? What did they think they knew? What did they think they understood? What do people who watch FOX News in the United States think they are learning? And how on earth can our mediums, our media, our ways of storytelling, the investigations, the lights on our screens, how can they be directed to form a counter argument? To form and shape the kinds of counter realities that we see in our lives.

So we need new forms of address and we need imagination. We can't look to Hollywood for these models, we can't look to the mainstream cinema for these models, as desirable as that financing might seem to be. I think that cinema has to stop colouring inside the lines. We have to move out of these established tracks. I think there's a kind of complacency that's set in, of how we created new sectors, ten years ago, twenty years ago, thirty years ago. And have been living in those lanes, have been swimming in those lanes ever since. Well, I think the lanes have changed. They are trenches now. And I think we need to create new meanings, and lines of connection, correspondences, as I once called it. And one of the great pleasures of this week has been hearing some of my words hurled back at me, that I'd forgotten, it's been kind of a treat, so thank you.

And to look back at our past, I mean, the past is not a scrapheap. I don't believe in that notion of progress. The scrapheap of the past is full of clues to the future. It's full of clues to move forward. The early feminist cinema that came out of and with, came of age with the early, early women's film festivals, was so powerful, with its force of discovery and its gathering of audiences, we need that kind of mobilisation and magnetisation again. The energies of the New Queer Cinema were legendary. Deservedly legendary. Why could it happen? It could happen because people were mobilised. Because of the AIDS epidemic, because people were dying. Well, once again, people are dying and we need new inventions. They must be reinvented. They must be redeployed and reimagined. Films that can capture the imagination can change the culture. Don't forget, I always love to say, you don't have to elect a movie. There are ways to change culture through film, and ways that culture can't be changed in any other way.

So another urgency, this question of intersectionality, that people have been talking about so much. So much more, considering that the critical legal studies scholar, Kimberlé Crenshaw, coined the expression in the 80s. It's funny how these things have come of age. The Bechdel Test has come back. Julie Dash has come back. Kimberle Crenshaw's term has come back. So you can see it's sometimes not an invention, it's a revisiting. But I think that intersectionality, increasingly, I think, has to be earned, not just learned. There's a fine line between intersectionality and cultural appropriation. And where are the films that can be so properly intersectional? Where is the film on the lesbians who co-founded Black Lives Matter? Where are the films on the queer people who form the core of the Dreamers, the undocumented youth in the United States? Where are the stories of the queer refugees coming on these boats through Lampedusa or through Lesbos? And I just heard from Michelle Aaron, who'll be up with me later, that there's a new film that was just at Sheffield, called Mr Gay Syria, so maybe those films are coming. But we have to know these lives. We have to understand who we're living in these cities with, who we're living in these neighbourhoods with - or not. We need films that tell those truths but we also need films that imagine alternative truths, alternate realities, different ways of living, different ways of thinking. The screens can lead us there, if they dare, if we look.

And so, I would love to think of a cinema of urgency, a cinema that can live up to that term. And so I'm calling for work that conjures, and to conjure the past, to conjure our past but also to conjure the pasts of our mediums and our histories, our theories and our criticisms. To look back for inspiration and to redeploy that. Whether it's the revival of Daughters of the Dust that's going on now, in all kind of places. There's a new season of Yvonne Rainer's work coming up in New York, I know there's been one here. Sally Potter's Golddiggers, which is available, finally, after so many years. The early work of Derek Jarman. The work of Isaac Julien who just won the Charles Wollaston Award for Western Union: Small Boats. The early work of Todd Haynes, with Poison and Superstar. As much as I love the new work, which I've begun to call, 'a nostalgia for repression', this is where queer cinema has ended - we're all nostalgic for the days of repression - and it's so glorious. I mean, how gorgeous to be Carol, back in the day. And yet, the ferocity of that early work. When there wasn't the leisure of such nostalgia because it was all around. Who will tell the tales to inspire us to take action? Where are these filmmakers? Where are these stories? Where are these investigations? Where are these truths? How can they be pictured? How can they be seen? Where can we find them?

And, it brings me around, in a way, climatically or anti-climatically, to the film we're going to see tonight. Because that was one of the first works of Cuban cinema I ever saw. I'd seen one or two of the classics, Memories of Underdevelopment, Lucia, some of those early, early works. But I was privileged to be invited in 1978 to go to Cuba. And it was before the film festival in Havana had even started. And it was the first time US critics and scholars had been invited. And we went, a number of us, and they were just finishing up a project to restore this film by a young Cuban director, who had died very tragically while in post-production on her first feature. And it was Sara Gómez. And the late Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, had been her mentor. And he was finishing the film, knowing what she was doing, she was recording the soundtrack, she was doing the final editing. But he worked very closely with her and with some others of her friends, worked to finish the film. And there's an interesting story behind it, showing here in 35mm, because, why would a rough black and white film, part documentary, part fiction, be made in 35. Well, because they didn't inherit 16mm technology in Cuba. They inherited the American commercial technology that had been there up until the 1959 revolution. They had 35mm movie theatres so they had to make 35mm films to educate the population, entertain the population. So apart from television what they had was 35. And, she had somehow got her hands on some 16mm equipment. So they had to go through this whole process of salvaging the 16 and transferring to 35 that held it up as much as finishing the post-production. Or so we were told. And she had died, and we heard this story by a Canadian, then filmmaker, Vivienne Leebosh, who we saw the night before we left, who said you have to go and see this family because they are still in such grief four years later. And so we did, we went and met Sara Gómez's mother and father and little daughter and talked to them and learned about her life. And learned the story of how she had died in an asthmatic attack on the night that her small daughter was hovering between life and death in a hospital. Her mother was a Santera, a practitioner of Santería. And Sara herself, allegedly, made a pledge that night - take me, let my daughter live. And the doctors had told her that if your daughter survives tonight she will live but if she's going to die, she'll die tonight. And that night her daughter lived and Sara died, you know, in an inexplicable extreme asthma attack.

And so, this myth, really impressed us all and we went there and we talked to them and we got to see the film. I was very very marked by it. And today, people talk about hybridity very easily, but that was not a model then. The fact that she moved between fiction and documentary in ways that we don't do now, in rather a different way, was very groundbreaking and the film became inspiring. It was shown in cinema clubs, it was shown at Third World Newsreel, people talked about creating a new radical film practice that could do this. And Sara herself had been an early follower of black liberation, she was supposedly the first Cuban to wear an Afro on the island. She had met everyone who had come from the United States. But my friend Justo Perez Quintana, who had grown up with Sara, they were best friends, said that she had grown up, as he put it, as a 'good little negro girl who played the piano'. And then she came and became a radical black filmmaker, and I would argue feminist filmmaker, who wanted to smash these boundaries, formally as well as in terms of content. She'd come out of documentary, she was a documentary filmmaker, and she didn't want to leave that behind when she moved into fiction. But she did move into fiction. And you'll see this is very much a 70s film. Certain kinds of 70s films have not weathered well, they sometimes seem kind of clunky, in terms of their dramaturgy or in terms of their characters. But hopefully you will bear with it because what she has done, I would say, is intersectionality avant la lettre. She has put race and class and gender together in this work. Official knowledge and street knowledge. Catholicism and Santería. All into one film because precisely they were all in her. She fought the leadership to tell her story to this day she's the only Cuban woman, of any colour, to make a feature fiction film, in what remains of that industry, which pretty much not much remains. And I would say, what she did it wasn't called intersectionality, but very much to use the term from Santeria, it could be called syncretic. The way in which different, seemingly oppositional practices, coexist in layers under one another, borne from each other, learning from each other, enriching and infusing each other. That's what she was up to. And little did I know we'd be here, screening this film, at the very moment that a maniacal US president has rescinded all the openings to Cuba. And once again, isolated the United States from the island.

So it's fitting that we should be seeing this, I'll be curious to know what you think of it and I'll be especially to be back on stage with Michelle Aaron, whose come to town to talk about the film, the key note and the ideas you may have about what cinema and video need to be doing now. How this moment of urgency can be met and how all of us cannot abrogate our own responsibility, our own mission. So, thanks so much.

[Applause]

MA: Something that I was reading that you said in Chick Flick, you talked about the historic mission, and I think you were talking about film at the time, in fact maybe it was this film. Now, putting that together with this idea of a cinema of urgency, I wonder how we achieve or how filmmakers achieve that cinema of urgency, perhaps when they're not living under the conditions of revolution in the way that Gómez was, in the post-revolutionary condition, or in the way that other people have been and are today, but maybe perhaps the aspiring filmmakers in this room... How might those films be made?

BRR: Well, I think I'm better at the questions than the answers, I'm afraid to say. You know, I remember talking with Gutiérrez Alea a few years later, and he was lamenting, observing that you could no longer make a film in Cuba by just going out in the streets and pointing your camera wherever, because, you know, the revolution wasn't happening anymore, like this bulldozer knocking down buildings. In fact, it's probably been a long time since any bulldozer knocked down a building in Havana, but, I think that that was already starting to be the case when she made this, really. But he was lamenting that was harder, that you had to go inside people to find it, you couldn't just go into the streets, it had to become interior rather than exterior.... Which I then use to talk about a new Latin American Cinema in the 80s, when that happened, or when I thought that happened. So, I suppose, you know, you have to live in terrible times, would be the easy answer, to make those kind of films. But I do think that our historic moment is calling out for a new kind of practice and I'm not sure what it is, I wish I knew, I would write a different article maybe. What startled me tonight about this tonight was that, and I just thought I'd mention it as I didn't beforehand, you know I talked about her dying young.... She was 31 when she died. She made this film when she was 30, I mean that's kind of incredible. It doesn't feel like a film by somebody who is 30-31, and yet it is, and that's also something to think about in terms of her mentality, her own aspirations, and what she thought was important and urgent.

MA: I know you said earlier about you've had lots of comments coming back and it wasn't deliberate... I wrote these down previously, even though I obviously want to please you. And also, what was so intriguing to me, this actually comes on Chick Flicks, page 101, and you say, 'a film that in no way condescends to its subjects', now - that, to me, is so fundamental to any cinema of urgency because it's about a kind of critical perspective. I think I've mentioned this before, something that Michael Warner said many years ago, talking about Queer theory and talking about ethics and specifically Queer terms, and he said that the 'Queer ethic connects with cutting through every hierarchy in the room'. And somehow, for me, that has always been an incredibly powerful idea, and then reading what you said about this film, in terms of her not condescending to anyone, and perhaps connecting to that sense of the Queer agenda, the intersectional agenda... I sort of feel like intersectional had to come back and pick up where Queer, which I think was inherently intersectional in its first moments –

BRR: Utterly. I do think that there is a way in which she's piercing through all of these different worlds with this, because clearly she's not Mario, and yet she's not that nice, white bourgeois teacher either. So where is she? Where is her voice located in this? Or, Germinal, the sound recordist who is her boyfriend at the time... And the film was often misinterpreted as being against Santería, because of the disapproval of deniego, the cult that he had been involved with, which was a different, a particularly different form of Santería. And the film has also been, I think, misunderstood because of that kind of narration, the English ways of narration. I remember people saying they were sure if Sara had still been alive she would've changed that, because it wasn't quite the effect that she wanted. I think they were saving money on subtitles, so like, this is the voiceover we can just have a separate English narration for it, that then throws it a bit. But, I do think that this question of not condescending to the subject is really important and it's what I've now started calling legibility. That the work should be legible to its own subject so that people who are the collaborators on the other side of the camera. And I think it is fundamental and yet I think that there are a lot of films that violate that, that are very, very far away from that kind of practice, and doesn't seem to be bother anyone.

MA: I think it's the majority and interestingly, in some ways, those films that are often focused precisely on the opposite can still fall foul of exactly that kind of notion. But, she's not afraid of showing the mess, and neither are you, and that's what's so wonderful about your books, it's that they're so rich.

BRR: They're very messy...

MA: No, no, I don't mean that. I mean, like, the mess of life. And that's the important stuff, they're not afraid of telling it how it is, and whether that's about opposing you know, any kind of institutional, theoretical, uh, zeitgeist. It's about being honest to yourself and to the text and to the times.

BRR: Well, you know, I always like to say that I grew up in a kosher house, and that it gave me a lifelong attachment to contamination. (Laughs) I have a har of purity campaigns, which I think has served me well in the United States, so as soon as I hear anyone set down the rule of how it's supposed to be, the minute they lay down the law, I have to start transgressing it. But, I do think it goes back to that Kosher household, which, by the way, was Kosher inside the house, but then we went on vacation and suddenly there were no rules anymore! It was sort of like, it was Carnival, and you didn't have to follow the rules anymore. And so, you go off to Cape Cod and you can eat bacon and lobster because you weren't home. So, you know, maybe it also prepared me for these illogical transgressions, I don't know... Sorry, I couldn't resist!

MA: I now have a favourite B Ruby Rich story. That's great. We have a roaming mic. Please can I ask that you wait until the mic comes to you, otherwise it messes up the sound.

Q1: Great stuff Ruby, that was just great. One of my questions here, is, you know, I get what you're saying, this idea of legibility, really beautiful word, but you're also talking to new urgences, and Millenials who are the kind of online generation etc. There's some great stuff going on on telly, but, at the same time, we, in the Cinema, it demands this of us. Which, is to sit in a space and have a time-bound, durational experience of event together in our differences, and you know, talk that through afterwards. And that's such a valuable thing, but you know, what, how? Because, the Cinema is this massive PR machine, and outside of that, these spaces of meeting the others and having those conversations, bringing into audiences into that without that cash, without that PR machine.... How are we going to do it? So, it's these troubling contradictions, really.

BRR: Yeah, well, you're raising a lot of really pertinent issues, and my thoughts are pretty much with yours, like, how do we solve this? And I think that there are some links that haven't been put in place still, between the online and the brick and mortar of universes. And I'm thinking that there must be some way to try to connect those up, through events that people haven't really conceived of properly yet. We're showing Strong Island, which will be the London premiere, it's just been at Sheffield, and it will be going out on Netlifx, and, I was at the Ford Foundation for a meeting about it in the fall, and it was a meeting for people discussing how could we re-use and organise around questions of the justice system, and questions of racial justice. And, it's a wonderful, wonderful film, I really urge you to come back and see it, but, some of the people there had a hard time with it because it's not instrumental, it's not a film that's made to just go out the door and be shown as a legal brief, it's very personal, it's set in a family, it's very much about black masculinity. And, coming out of that, I ended up talking to somebody who had gone recently to work for Ford, and he was all excited because he was living in Harlem, and he said he'd come out the door to take out his garbage, and people were out in the street and they were out and involved in this really, really agitated conversation, really discussing something with great passion, and he was curious what was going on, like had there been a robbery on the block, what was happening... and then he listened in, and discovered they were all talking about Ava DuVernay’s 13 th . The documentary about the history of the criminal justice system and slavery. That was going out on TV and online. And all these people in this neighbourhood had seen it and were talking about, and he said 'when was the last time that ever happened?'. So, even though it might have had adamant viewings, because it hit that week and it was also the opening night film for the New York Film Festival, and it was getting all of this push and critical mass in the culture at large. They all knew about it, they had all seen it right that week, and they were discussing it. And it was the audience it was intended for, it wasn't a film festival audience, it was a black neighbourhood audience. And he was so thrilled, he'd just come to work and he said, 'I'm working here now, and look what affect this has had, and that we can think about this in this way'. And, Strong Island is a very different film, but it will go out on Netlifx. So, what does that mean? Who the hell is watching Netflix? And what kind of algorithm is delivering their choices to them, right? We don't know. But I think there are some in between spaces that need to get created, to make some of linkages. And, you're right, we're not even meeting each other, we're only meeting people we've known for years because we're all too busy or atomised. But, amusingly, this film ends in this way because Cuban films at that moment was dedicated to having what they were calling open endings, because they would then put the lights on in the whatever halls they were showing the films in, and get people to continue the arguments, and have these debates. And there are number of Cuban films from this period that end way, with the notion of the open ending. So, some of these questions have to be figured out structurally in terms of the work itself, and some of it has to be figured out, I think, in ways that we are using the online platforms, and how we bring them offline. We don't have a good online/offline shuttle at the moment, it's kind of one or the other. You know, talking to young people, talking to my students, they do not understand the notion of the public. When I say to them, when you're watching these alone at home, don't you miss being in an audience with other people, don't you miss being part of a public? And they really don't understand the word public. They don't understand what I'm talking about. And they say, 'but, yes I'm watching with all my friends, we're all online at the same time, and we've got Facebook chat open, and we have something else open, so we're all watching it together, what are you talking about?'. So, there's something that I don't understand and something that they don't understand, and in between us, I think might be clues to how we can start to look for ways to reconfigure that circuit.

MA: I'd like to pick up on that a little, and it's also in response to what you were saying in your Cinema of urgency. Isn't there one, I mean, certainly, as someone who, well, having spent many, many years watching lots and lots of films about atrocity and war crimes etc, I've been watching a lot of films from coming out of the Arab uprisings as well, those films seem to me to be having many of these qualities of you know, not condescending to their subjects. My struggle with it, is no mention of queer, here. And I wondered what the Queer would be…

BRR: Yeah, I'm not sure, and that's my curiosity about the Black Lives Matter film that hasn't been made yet, or the Dreamers film that hasn't been made yet. That probably needs to be a fiction film if it needs to work that way, it needs to be more like a Fruitville Station than13th. I don't know, we haven't seen it yet, and yeah, gender tends to always move to the back of the bus with these things. Because something else is seen as more urgent, there's always a hierarchy somehow, within urgency, that I would want to dispute. This is where I just keep thinking that we need to figure things out, and that even though the urgent documentaries coming from different parts of the world or landing at the documentary festivals.... Where are they moving outside of there? How are people finding them and then what are they doing with that? And do we have those kinds of documentaries for our own lives, whether it's here in London or often San Francisco or often New York. I mean, San Francisco has been beset by horrible criminal evictions for more than five years now, more recently of a ninety-nine year old woman who then died from the stress of having to leave her home. And this is happening all over the city, which is now a kind of Google waiting room or something. And, I haven't seen a film about that yet, I mean I've seen a documentary about the evictions made by a student, a grad student of mine, which I'm thrilled with, but this isn't the stuff of narrative still, this isn't the stuff of drama still... and television is doing a lot and television is very exciting. But, it still hasn't reached some of these places. A lot of our lives seem to not be passing in front of cameras, at east, not yet, and I know it's not instant feedback loop, and you know, maybe it's a bit silly to expect so, but I think that times are so dire that people need to be doing this and thinking about this.

Q2: Thank you so much for showing us this film. I can remember seeing it when it was screened briefly in Britain in the 80s. But, what surprised me in seeing it again, was speaking of hierarchies, there's the workers’ council, which is inexplicitly patriarchal institution. Te father of the protagonist is chair of the council, it's entirely men or nearly entirely men.

BRR: Seems to be entirely.

Q2: Yeah. I'm curious about how those hierarchies were seen to be critiqued or not critiqued in the film.

BRR: Yeah, well I think it's not critiqued in the film, frankly. I think it's the workers' council of that factory, so they're very gendered universes between who is teaching and who is working in the factory. I don't think there's a critique of the father, I think there's a kind of tacit acceptance of some of these so-called revolutionary formations that certainly wouldn't be true of a film made today. I don't think there's a critique of gender within that kind of workplace situation, there's a critique of gender within the relationship, and it's really Yolanda's critique of how she's being treated. But, uhm, the revolution was less than partial when it came to gender and frankly when it came to race. I think it did some things very well and some things very badly, and now it's all falling apart. I think, just to say, she's been documenting situations in different neighbourhoods in documentaries. A lot of these documentaries are available now. They didn't use to be, and I know people are starting to work on them, about life in the slums, about questions affecting women who couldn't affect childcare, all those kinds of things. And, very explicitly here, about how badly women are fearing their own relationships, whether it's a woman with too many kids or the woman who's being beaten by the husband or boyfriend or whatever. And you see this attempt within this fictional couple that she puts at the centre of the film to work through that in some kind of way, still left arguing at the end the same way that the workers in the factories are still left arguing in the end. We don't return back to the school. But I think that's kind of as far as things got at that moment and she was clearly trying to push it with some of this, and other parts she wasn't pushing, but this would've been the first of many films, I mean it's very sad. It doesn't explain why no other woman ever made a feature film in Cuba, because that same patriarchal structure of the workers' council was the same patriarchal structure of ICAIC, the film institute. It was horrific. It was ridiculous.

Q2: Could you say something about how the film was received? If, at all?

BRR: Mh, I don't know, because you always got this through other Cubans that you talked to, so, we were at the film institute, actually, it hadn't even been released yet that first time, there was a lot of support for her on the part of Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Titón, but Santiago Álvarez hated her and didn't want to, you, know, deal with her and even within the hierarchy of fiction filmmaking, I doubt that she would've made the film if it hadn't been Gutiérrez Alea as her mentor championing her. And Julio García Espinosa has also credited in the credits, also supporting her. So I have no idea really how it was received and all of that is... I mean, how are films received in Cuba? I mean, what do you say? Who gets to go to the movie theaters, who's there, what do they say publicly, what do they say privately, it was always a very complicated set of data, shall we say. It wasn't received as enthusiastically as it was in the US or in certain parts of Britain, certain parts of the US - I don't know. I think that people within the film institute really valued it, but to what extent it went out and actually entered into these kinds of sectors that she was trying to reach once she wasn't there, to carry it, I don't know.

MA: I'm very sorry, but we have to draw it to a close already, so I just have to thank Ruby for an amazing talk and an amazing discussion and for bringing the film to us. Thank you to you too.

BRR: Thanks Michelle, thanks everyone. Thanks for listening to this Barbican ScreenTalks with B Ruby Rich.