Crafting the perfect sound

What makes a good violin? Violin maker and restorer, John Dilworth, investigates the history of violin making.

Tommy Cooper used to tell a joke about a man with a violin and an oil painting. The dealer looks at them and says, ‘I have good news and bad news. The good news is that you have a Stradivari and a Rembrandt. The bad news is that Rembrandt was a rotten violin maker and Strad couldn’t paint for toffee.’

The joke sums up the general understanding of four basic things about violins. An old violin is a good one. The best violin maker was Stradivari, who was Italian. And they can be worth a lot of money.

A romanticised illustration of Antonio Stradivari.

A romanticised illustration of Antonio Stradivari.

It is hard to think of another musical instrument maker whose name is as widely known to the public, except for perhaps Leo Fender or Henry Steinway. Stradivari lived and worked in Cremona three hundred years ago, and his instruments now routinely sell for multiple millions of pounds. He was not alone in Cremona however, and other revered ‘luthiers’ of the period (as violin makers are still known) include the Amati, Guarneri, Rugeri and Bergonzi families- all working in this small provincial city during the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, and all carrying with them a similar reputation for distinction in tone, and financial value. These are the instruments professional players still aspire to. To have as the everyday tool of your trade an item worth a million pounds and over two hundred years old is not unusual for string players. Violins are clearly exceptional objects.

'Part of the mystery and fascination of a fine Stradivarius is that it has a soul and a personality of its own. For the violinist, this means that the violin seems to play the player'

Satu Vänskä, Principal Violinist of the Australian Chamber Orchestra

Age as a desirable factor in musical instruments is not confined to the violin family. In Japan, traditional instruments are also considered to mature with age. In fact, the same conversations are now being had about ‘old’ electric guitars, vintage drum kits and even synthesisers and amplifiers having particular tonal qualities that cannot be found in newer models. How instruments seem to store up tone and acquire greater quality over time is a sincerely and widely held belief amongst the musicians that use them.

Satu Vänskä, Principal Violinist of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, performs JS Bach's ‘Allemande’ from Partita II in D minor on the 1726 Belgiorno Stradivarius.

Watch Satu Vänskä, Principal Violinist of the Australian Chamber Orchestra, perform JS Bach's ‘Allemande’ from Partita II in D minor.

Blind tests of violins are notoriously inconclusive; an audience will just as often pick a bright new instrument over an aged and more valuable one because it stands out. But ask a player to pick an instrument for themselves, and they will probably choose the oldest one on offer. Listen to it and you will hear an intensity of sound. To articulate it in words, you quickly resort to the language of a wine taster, talking of ‘floral top notes and woody undercurrents’. There are these subtle colours contained within the sound, but there is something about the sheer concentration of energy, presence and focus in the tone of a fine old violin that transcends words. It is not just about the mystique of playing an instrument that was actually used by Kreisler, Heifetz or Menuhin, although this is undeniably and naturally also a strong factor.

The unique thing about violins is that they have been allowed to age. Countless bizarre forms of brass, woodwind and keyboard instruments can be seen in museums and conservatoire collections. They are there because they have become obsolete at some time or another. Most orchestral instruments have been in their present form for no more than a century or so, but violins have never been unfashionable or impractical. They are not fixed in pitch like a piano or a clarinet, and can freely adapt to any tuning, any scale, any temperament. Most musical instruments are quite mechanically complex, and can be both fragile and at the same time subject to developmental improvement. A violin is basically a box. There is no mechanism to be reinvented, there is nothing to become obsolete. But then to sound at all, everything depends on a thin vibrating leaf of wood that is at the same time supporting several pounds of pressure from the tightly stretched strings.

How does such a thing survive hundreds of years of use?

It is a box designed like an egg, that is massively strong in the way it needs to be, but vulnerable to a sharply tapping beak. A violin is all curved surfaces, with great compressive strength, but like an egg, still vulnerable to a sharp tap. It will crack if it gets knocked, and although every great old violin has a crack (or several) in it somewhere, it is very rarely fatal. One of the many fascinating things about the violin is that it was designed to be repaired. Unlike a lute, or a viol, or a guitar, it has an overhanging lip around the edge. The sides, or ‘ribs’, do not come flush with the edge of the top and back, but are tucked a couple of millimetres in. This simple feature of the violin family means not just that the ribs themselves are protected, but that the instrument can be relatively easily dismantled. The overhanging edge provides a safe place to insert a thin knife that will split the glued joint and open the instrument like, well, like an egg. Any little crack can be glued up as good as new, and other maintenance carried out by a skilled hand. Realignment of the parts is also made easier by the margins of the overhanging edge.

'If age is the magic ingredient that makes the sound of an instrument attractive to the human ear, violins have the unfair advantage...'

There are today Stradivari instruments that have fallen from cars and lost at sea, and brought back to life. Nothing, short of fire, seems to be fatal to a violin. They can even acquire a new lease of life when two are joined together, like the violin owned by the Australian Chamber Orchestra and played by Glenn Christiansen, which is in fact made up from surviving parts of two different Stradivaris of similar period. This process is not altogether uncommon. Violins endure, and mature in a way that is denied to other musical instruments. If age is the magic ingredient that makes the sound of an instrument attractive to the human ear, violins have the unfair advantage.

The idea of building for longevity must have been a significant change of thinking by early violin makers, and the first we know of by name was Andrea Amati, working in Cremona from about 1540, and astonishingly, some of his instruments are still being played professionally today. We can say confidently that Andrea Amati was responsible for making Cremona the cradle and home of the violin.

Cremona itself would have provided him with a ready clientele. Although today overshadowed by the magnificence of so many other Italian towns, throughout the renaissance Cremona had its own cultural identity, with a very strong musical culture. In the sixteenth century Cremonese players were at the core of court ensembles across Europe and are even to be found in the royal band of Henry VIII in Whitehall. Monteverdi was born and studied in Cremona before being recruited by the Mantuan court in about 1590.

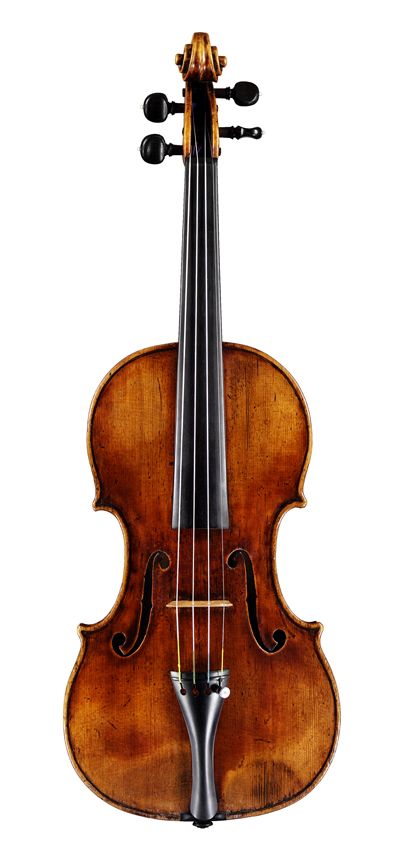

1728/9 Stradivari violin

1728/9 Stradivari violin

1728/9 Stradivari violin

1728/9 Stradivari violin

Timo-Veikko Valve, principal cello at the Australian Chamber Orchestra, performs JS Bach's Sarabande from Suite No 4 for Unaccompanied Cello BWV1010 in E-flat Major at Milton Court - on an Amati cello.

Through this diaspora of Cremonese musicians Andrea Amati developed a reputation abroad. He is best known today through a set of decorated instruments he made for Charles IX of France (two of which are in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford). What probably differentiated Amati’s instruments from any other contemporary work is the consistency and finesse clearly invested in them. They are worked up from careful and detailed designs, not improvised or makeshift in any way, and the materials chosen have become definitive for all violin makers right up to the present. The precisely geometrical turns of the scroll, the definitive form of the soundholes and even the slender black and white inlay around the edges that are familiar parts of the violin today are all derived from his original patterns. He was a thoughtful, ambitious, and flawless craftsman, working for a new class of professional musicians. His concerns embraced durability along with visual and tonal beauty.

Andrea Amati, in modern terminology, established a brand. His sons, Hieronymus and Antonio followed him, slowly evolving certain aspects in their own way. Hieronymus’ son Nicolo, thought to be the greatest craftsman of the family, continued and expanded the workshop, even through the disastrous plague years in the city in the early 1630s, teaching students from outside the family, and even from outside Cremona itself, a very indicative change in the old workshop tradition. One of these pupils may have been Stradivari himself.

A dated inscription from Hieronymus Amati inside a 1590 Amati violin

A dated inscription from Hieronymus Amati inside a 1590 Amati violin

Antonio Stradivari emerged as an independent violin maker in about 1666. His impact on the violin and on Cremona’s status in general has been immense. Not content to follow Amati designs slavishly, he was an experimenter, as innovative as Andrea had been one hundred years previously. Around 1700 he began to flatten and compress the arching- the swelling shapes of the back and front, to produce a new and more powerful sound. He also developed the varnish from the simple honey-coloured coating that Amati used, to the dramatically intense red-brown tones that have themselves created an extraordinary mystique. He made beautifully inlaid instruments for the court of Spain, and won commissions from princes, dukes and cardinals. To be ‘as rich as Stradivarius’ became colloquial in the city during his own lifetime, which extended for 93 years; his last instruments proudly bear his own annotation ‘de anni 93’ to the printed label. In that time, assisted by his three sons, he made more than 700 instruments, a phenomenal output, and incidentally another important factor in building a recognisable ‘brand’.

In some ways though, Stradivari seems to have sucked the energy out of Cremona’s violin making community. His sons achieved little on their own, and within a few years of his death in 1737, the craft collapsed. His near contemporary in Cremona, Giuseppe Guarneri, known as ‘del Gesu’, is today viewed his only real rival, but died very soon after in 1744.

Guarneri del Gesu was as revolutionary in violin making terms as Stradivari, bringing a radical vigour and variety of aspect into his work. He engineered a new tonal weight and depth, but it took another great revolutionary of the violin, Nicolo Paganini, to grasp the potential of these instruments almost a century later, and the violin he played throughout his life which he called his ‘Cannon’, made by Guarneri in 1743 is one of the most influential violins in history. Paganini’s playing provoked a huge demand for Guarneri’s work amongst his followers.

Richard Tognetti plays on a del Gesu of the same year, named after the nineteenth century English player influenced by Paganini, J. T. Carrodus, and today leading soloists seem in some ways defined by their loyalty to either Stradivari or Guarneri, and their subtly differing tonal qualities. Guarneri’s gifts were not enough to save the Cremonese tradition however. After him, a veil descended.

What probably happened is that cottage industry copies made in large quantities in Germany and France gradually choked off demand for high quality work, and individual makers who had set themselves up in towns and cities throughout Europe struggled to maintain a good standard, let alone make any breakthroughs of their own in design or performance. The Cremona ‘brand’ thrived though, a well proven route to collectability and investment value. ‘Buy land, they ain’t making it anymore’ advised Mark Twain.

Well, they weren’t making violins in Cremona for a while either.

Guarneri del Gesu violin, 1743. Played by Richard Tognetti.

Guarneri del Gesu violin, 1743. Played by Richard Tognetti.

Guarneri del Gesu violin, 1743. Played by Richard Tognetti.

Guarneri del Gesu violin, 1743. Played by Richard Tognetti.

'There is so far no evidence of any good violin simply ‘wearing out’ or losing energy, and no reason to suppose they ever will'

The Cremonese violin has remained the paradigm of violin making, a rare example of a perfected design that has defied improvement, and has actually improved itself, naturally, with each moment of passing time.

Amatis, Stradivaris and Guarneris were the best instruments being made in their own time and will continue to be the gold standard for violin makers everywhere. There is so far no evidence of any good violin simply ‘wearing out’ or losing energy, and no reason to suppose they ever will. The good thing is that the ever-escalating prices of these great instruments has created a good environment for new makers providing the painstaking but expensively time-consuming effort that goes into making a fine instrument that will mature in the Cremonese tradition. There seems to be at the moment a new ‘golden age’ of violin making. Science now provides huge insights into the methods and materials used by the old masters, and widespread sharing of information amongst what was once a reclusive and closed profession is enabling modern makers to provide new instruments which are more closely matched in tone to instruments of the classical period, and which will age and develop as they have.

About the author

John Dilworth trained as a violin maker at the Newark School of Violin Making, Nottinghamshire and was subsequently employed as a violin restorer at J & A Beare, violin dealers in London. Working independently from 1991 as a violin maker and restorer, he has been a regular contributor to the Strad Magazine, and acted as technical editor from 1998 until 2018. He continues to make and restore violins, violas and cellos.

Photography and video footage kindly supplied by J & A Beare and the Australian Chamber Orchestra

The Australian Chamber Orchestra, our International Associate Ensemble at Milton Court, have an incredible selection of Golden Age instruments in their possession, which contribute to the distinctive sound and tone of the orchestra.

Browse upcoming classical music events at the Barbican.