Vanessa Winship:

she dances on Jackson

In an extract from Vanessa Winship: And Time Folds exhibition catalogue, photography historian David Chandler reflects on Winship’s Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation award-winning body of work: she dances on Jackson.

A visual poet, contemporary British photographer Vanessa Winship’s luminous black and white photographs are concerned with the elusive qualities of fragility and transience in both our landscape and society. Her

images of landscapes and communities alongside individual portraits are inextricably marked by their place within history, fragments of memory anchored in the past as much as the present, unfixed and ever changing.

A wanderer by nature, Winship has amassed a body of work that moves surefootedly between genres - reportage, documentary, portraiture and landscape – as well as diverse and peripheral geopolitical territories.

In this extract from the exhibition catalogue for Vanessa Winship: And Time Folds, photography historian, writer and curator David Chandler reflects on Winship’s Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation award-winning

body of work: she dances on Jackson.

she dances on Jackson

2011–2012

For British photographers with serious ambitions, the idea of photographing in America is at once an alluring and forbidding prospect. Especially for Winship’s generation who came under the formative influence of post-war American photography as it gradually found its way into Britain through books and occasional exhibitions during the 1970s and 80s, the American social landscape was most intimately known through photographic images, and through the iconic works that had sought to define the great sweep of a national culture while exposing its troubled psyche.

'We are in the wake of the American dream, in the dusty sidings of industry and commerce...'

We are in the wake of the American dream, in the dusty sidings of industry and commerce; but it is precisely here in the well-worn vernacular culture of the country that Winship imagined, as so many photographers before her had done, she

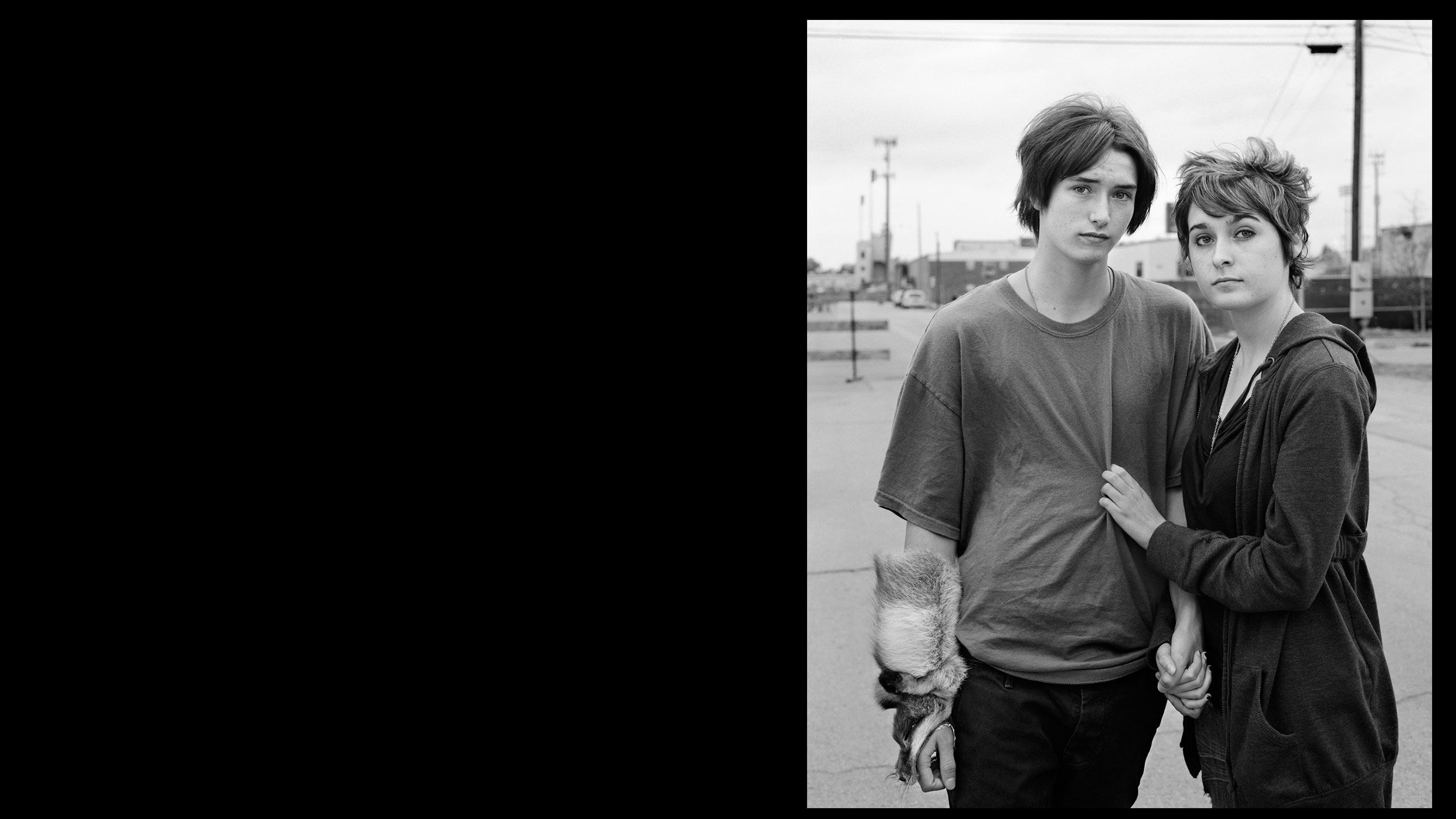

might find the ordinary and the anonymous, ‘the lives left behind’ that turn out to be at the very centre of things. And in this sense, it is Winship’s portraits, born from her chance encounters with people, which

elevate, and to some extent redeem, the downbeat vision of she dances on Jackson.

Here, in these exquisite pictures, arguably at the apex of her entire photographic work, we find the young survivors and rebels who come forward as representatives of the landscape; they are the junction points where it speaks most clearly

and directly, and where it returns our gaze as if to ask its own questions of us.

'The young survivors and rebels who come forward as representatives of the landscape...'

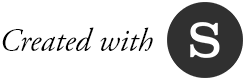

In the edited sequence of she dances on Jackson, this imaginary binding of people and place is inferred at strategic points by landscapes that precede or follow the portraits: the gentle ripples on a lake, then the silhouette of a violently bent roadside tree providing a material and sensory context for the haunting portrait of a man with a bare tattooed torso that follows.

Similarly, a few pictures later, an immaculately turned out bridesmaid stands on a stretch of waste land, an old iron bridge receding in the background to the right. In the next photograph, we see another iron bridge, with what appears to be a dilapidated wooden shack perched at its centre; the care and attention of the woman’s appearance more resonant, and resilient, in this forlorn rustbelt landscape of industrial relics.

The portraits in she dances on Jackson are moments of connection and intensity that punctuate and sustain the sequence. But they also represent the real human exchanges that sustained Winship’s fractured journey around

America and that she had sought in her work since Sweet Nothings, a series of 5x4 portraits of young Turkish girls produced in 2007.

The full stories of some, including the episode in Jackson which gives her work its title, are recounted in her journal pages and constitute an important parallel narrative in the work. And then, in a small number of portraits vital to its overall tone, the implied physical proximity and connectedness of the work is given tender form in the touches and embraces of a series of couples photographed together.

'The art of posing gives way to spontaneous gestures of affection...'

In almost every case the art of posing gives way to spontaneous gestures of affection that express the power of human relationships by their very arbitrariness: a young woman lightly pulling on her boyfriend’s tee-shirt, or the boy who, as he turns to look away, gently reaches back to hold his father’s ear between his fingers; a touch of such untold warmth and mystery that it might stand as a fitting emblem for the work as a whole.

Although Winship’s she dances on Jackson is inscribed by the fault lines of sadness and loss, and by much uncertainty, it was the revelatory nature and enduring intimacy of these human encounters that finally offered the

photographer a form of redemption.

About Vanessa Winship:

And Time Folds

The first major UK solo exhibition of contemporary photographer and recipient of the prestigious Henri Cartier-Bresson prize in 2011, Vanessa Winship. This much overdue exhibition showcases over 150 photographs, uncovering the fragile

nature of our landscape and society and exploring how memory leaves its mark.

Part of a photography double bill with pioneering documentary photographer and visual activist, Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing.

Part of

The Art of Change, our 2018 annual theme which explores how the arts respond to, reflect and potentially effect change in the social and political landscape.

Photos: she dances on Jackson. All works Untitled, 2011-2012. © Vanessa Winship