Karlheinz Stockhausen is a name familiar to many who are engaged with the arts. Lots of people have heard of him even if they have not heard his music. His reputation extends far and wide and often it’s his reputation, rather than his work, that informs opinions.

Right from the outset he was a controversial figure. In the early 1950s his music caused outrage, even among his colleagues in the avant-garde. In more recent times he was often derided for his comments about being from Sirius – a star in the constellation Canis Major – but it is rarely reported that he mentioned this as occurring in a dream. In 1990, a book reviewer wrote in a scholarly journal, ‘Some of what he has to say certainly helps but a fair amount of it is so woolly, fanciful or downright unbelievable that it simply has to be dismissed.’

But, in the history of Western music, very few composers have made significant, far-reaching changes to the way music is composed, performed and heard, and Karlheinz Stockhausen is one of those few. His work has had a profound impact on the very idea of music: what it is, how it is made, its nature and its purpose. He invented new sounds and new ways of putting sounds together and, consequently, he changed the ways in which music may be perceived and the effect that it has upon us.

'The post-war composers were inventing new ways of putting notes together...'

At this time, Western music was undergoing the most astonishing upheavals: the very idea of its nature and purpose was being redefined by the avant-garde in Europe and America. The conventional notions of melody as a memorable line of notes, something that might be sung by anyone going about their daily business, was completely disparaged by the post-war composers who were inventing new ways of putting notes together.

'...because they no longer wanted to write tunes they had to find other ways of putting sounds together'

In Europe, the most important of these new methods was serialism, a compositional technique that grew out of the intensely chromatic music of the late 19th century and the twelve-tone music of Schoenberg. Composers worked with the idea that all the characteristics of sounds - pitch, duration, dynamics, timbre, etc - could have equal importance. And because they no longer wanted to write tunes they had to find other ways of putting sounds together.

For Stockhausen, serialism was the way this was to be done. In 1971, having worked with this method for twenty years, he said 'Serialism is the only way of balancing different forces. In general it means simply that you have any number of degrees between two extreme that are defined at the beginning of a work, and you establish a scale to mediate between these two extremes. Serialism is just a way of thinking.'

This era of musical evolution eventually led to a focus on sound itself as the essence and substance of music. These kinds of changes had already occurred in the fine arts where Cubism, and then Abstract Expressionism, had displaced the straightforward representation of recognisable everyday life; and in literature the idea of a linear, comprehensible narrative had been subverted by James Joyce, Virginia Wolff, T S Eliot and others.

Stockhausen’s early years are important in formulating an understanding of his work because they established the guiding principles and methodologies that he employed throughout his life.

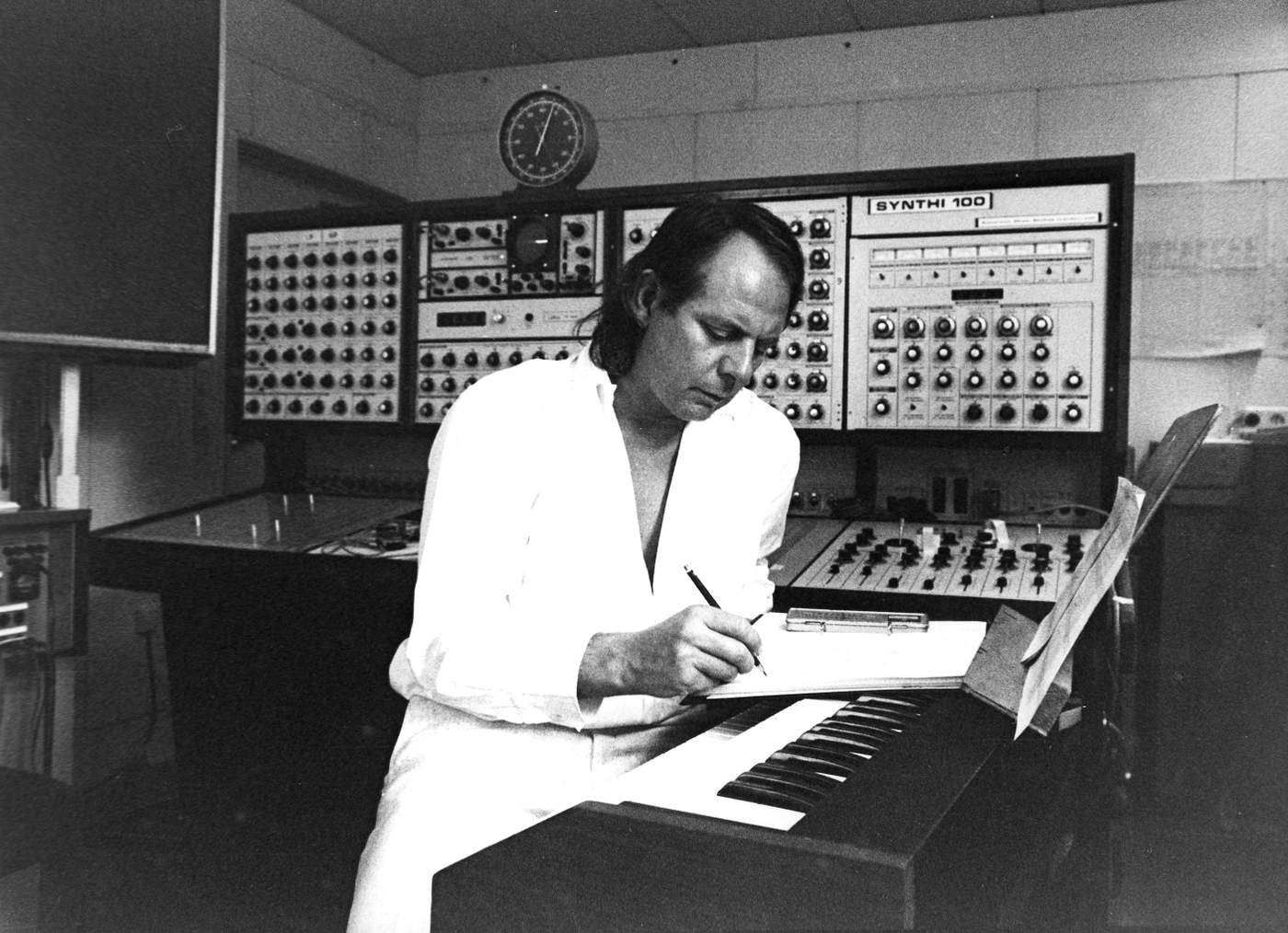

Just before Stockhausen went to Paris, the radio station in Cologne, Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), established the Studio for Electronic Music of the West German Radio. This studio focused on ways of creating entirely new sounds using electronics; sounds that had never been heard before. Nowadays this can be easily achieved on a mobile phone but in the middle of the 20th century it would have been similar to inventing a completely new colour.

Working continuously between July and November of 1953, at the WDR studios, Stockhausen made his first piece of purely electronic music, Studie I. This ten minute work was based on a complex fusion of sine tones, the eerie, ethereal whistling sound familiar from a myriad of low-budget sci-fi films. These fusions created unearthly clanging, dark rumbles and what Stockhausen called 'Raindrops in the sun …'

In 1954 he went on to compose another electronic work, Studie II. This was made using noise based sounds that Stockhausen synthesized by blending sine tones in a large reverberation chamber. Here, the term ‘noise’ has a precise technical meaning that refers to sounds similar to consonants like ‘shh’, ‘fff’, ‘sss’, etc: it doesn’t mean loud, unwanted or irritating sound. After many months of intense work Stockhausen produced a three minute piece comprising soft, ringing, hissing tones that sometimes float and glide and sometimes stumble and stutter.

These two studies were not made using electronic instruments with familiar piano-like keyboards; they were made using sine tone oscillators: clunky electronic devices that were primarily designed for testing equipment used at radio stations. All sounds can be broken down and analysed into sine tone components; these are the ‘atoms’ from which sounds are built. In the 1950s, composers at the WDR studios were using these techniques to create sound. The emphasis was on precision and control with almost every detail prescribed by the composer; characteristics that might be said to define Stockhausen’s approach right until the end.

'Creating electronic music is no longer this arduous...'

Stockhausen’s third piece of electronic music was Gesang der Jünglinge (Song of the Youths), composed at the WDR studio between 1955 and 1956 and, for the first time ever, this combined the sound of a human voice with electronic sound. A sung Biblical text was recorded and cut into fragments - phonemes, syllables, words and phrases - which were then combined with electronic versions made with sine tone oscillators, pulse generators, noise generators and filters. The incredible amount of time and concentrated, detailed labour that Stockhausen and his team spent making this piece is now difficult to comprehend: creating electronic music is no longer this arduous.

The composed material was transferred onto four spools of magnetic film stock on a machine used for creating film soundtracks. Stockhausen had the vision to connect the output of each of the separate spools to four individual loudspeakers, each located in one of the corners of the concert hall.

He had, in 1956, invented what we now call surround sound.

'This was completely new; nobody had witnessed anything like this before'

Today, it is almost impossible to imagine how the audience at the world premiere of Gesang der Jünglinge would have felt and responded as swarms of sound, vocal and electronic, flew in space around them. This was completely new; nobody had witnessed anything like this before; it was a musical experience the like of which has never been surpassed.

Towards the end of the 1960s Stockhausen made live electronic works that he called ‘process music’. Several of these works involved sounds plucked from the ether, via shortwave radio, which are emulated and transformed by performers according to procedures set out by the composer. Every performance sounds utterly different because what is picked up by radio receivers is unpredictable and unknown until the very moment it is heard by the performer and audience alike. The scores comprise elaborate graphics, diagrams and symbols that signify processes undertaken with musical parameters - pitches higher/lower, durations longer/shorter, dynamics louder/quieter, etc.

Nonetheless, all these procedures hark back to the early days of the first piano pieces, the electronic studies and the instrumental works that are built from the rudimentary elements of sound.

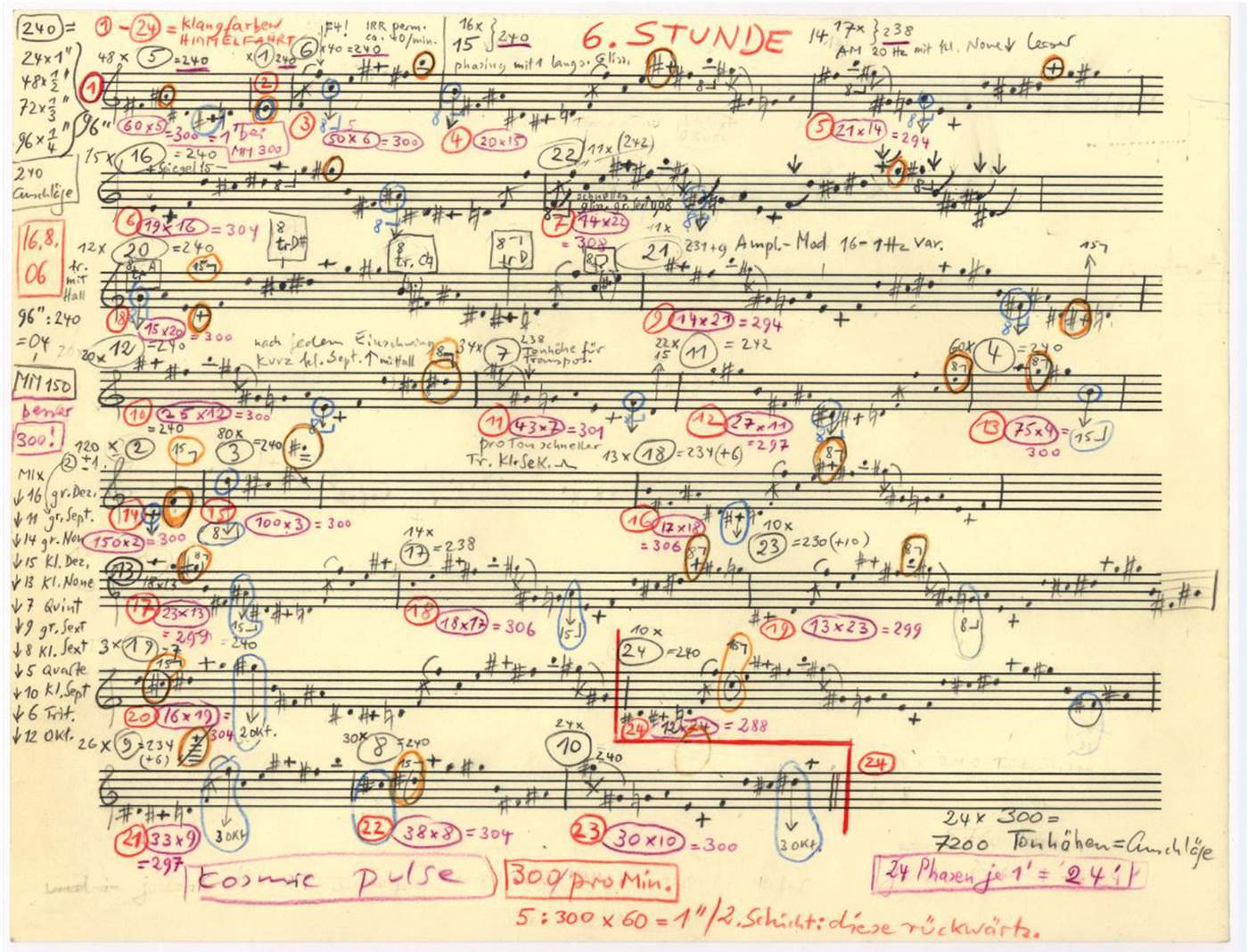

Cosmic Pulses was composed in 2006–2007, it is the 13th part of the Klang cycle, based on the 24 hours of the day, and it is Stockhausen’s last purely electronic work.

It is composed from 24 melodic loops, comprising from 1 to 24 pitches, in a range of seven octaves. These loops rotate at 24 different speeds around 8 loudspeakers. The loops are successively layered together from low to high and from the slowest to the fastest tempo. In March 2007, Stockhausen compared the experiment with ' …the virtual job of synchronizing the orbits of 24 planets around a sun, with individual rotations, tempi and trajectories.'

Typically, Stockhausen has published information about how the piece was composed and this detailed diagram, drawn by him, is a form scheme that represents what occurs in the piece. It may not look like a conventional musical score but, just as the printed music of a Mozart piano sonata indicates what occurs in the piece, this diagram represents the activity in Cosmic Pulses.

When he had completed the spatialization of the piece Stockhausen said, 'If it is possible to hear everything, I do not yet know – it depends on how often one can experience an 8-channel performance'. At the Barbican, in November, we shall be able to hear the piece as Stockhausen intended and to fly in his multi-dimensional world.

At the same time as developing work in electronic music, Stockhausen was writing music for conventional instruments. He composed a series of sharp, dazzling piano pieces, that he described as ‘sketches’ for the electronic works; a wind quintet Zeitmaße (Time Measures), that pushed rhythmic structure to an extreme; a vast opus for three orchestras, Gruppen, where instrumental sounds swing left and right across the concert hall, and a percussion solo, Zyklus, the score of which may be read any side up creating the idea of a cycle with no beginning or end. How he managed to complete all these innovative, complex works in such a relatively short time is utterly baffling.

In addition to Serialism, Stockhausen was guided by a deep spirituality, a sense that he was simply a conduit through which this music flowed and found its way into the world. He was brought up in the Catholic faith but formally broke with the church in the late 50s. For him, the serial method of composition and the serial way of thinking was 'a spiritual and democratic attitude toward the world': it was a way of connecting and unifying all experience and all that exists.

In May 1953, in a letter to his friend and colleague the composer Karel Goeyvaerts, Stockhausen wrote 'Recently I’ve been thinking a great deal about the fact that each instant, each new sound, each new note in a piece of music ought to be wonderful, bright and joyous, unpremeditated. Just as each flower in a huge field of flowers has its own beauty, and just as no beauty needs to be less beautiful because of the others. The Lord God is the artist above all artists …'

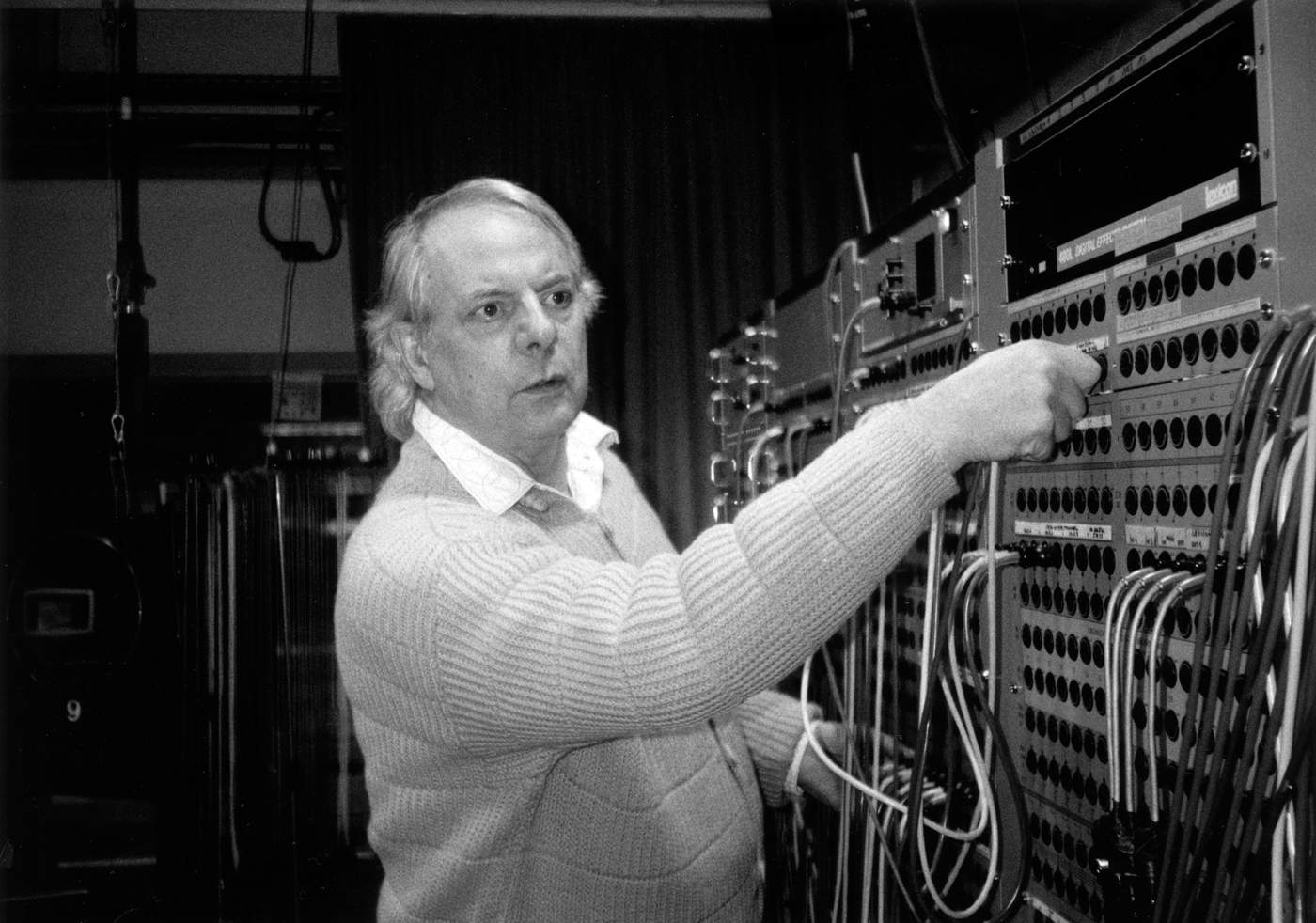

In the 1960s he developed ways of combining electronic music with conventional instruments, in real-time, live performances. Previously, most electronic music had been recorded onto audio tape and projected into the concert hall through multiple loudspeakers. Kontakte, composed in 1960, is for piano, percussion and 4 channel tape.

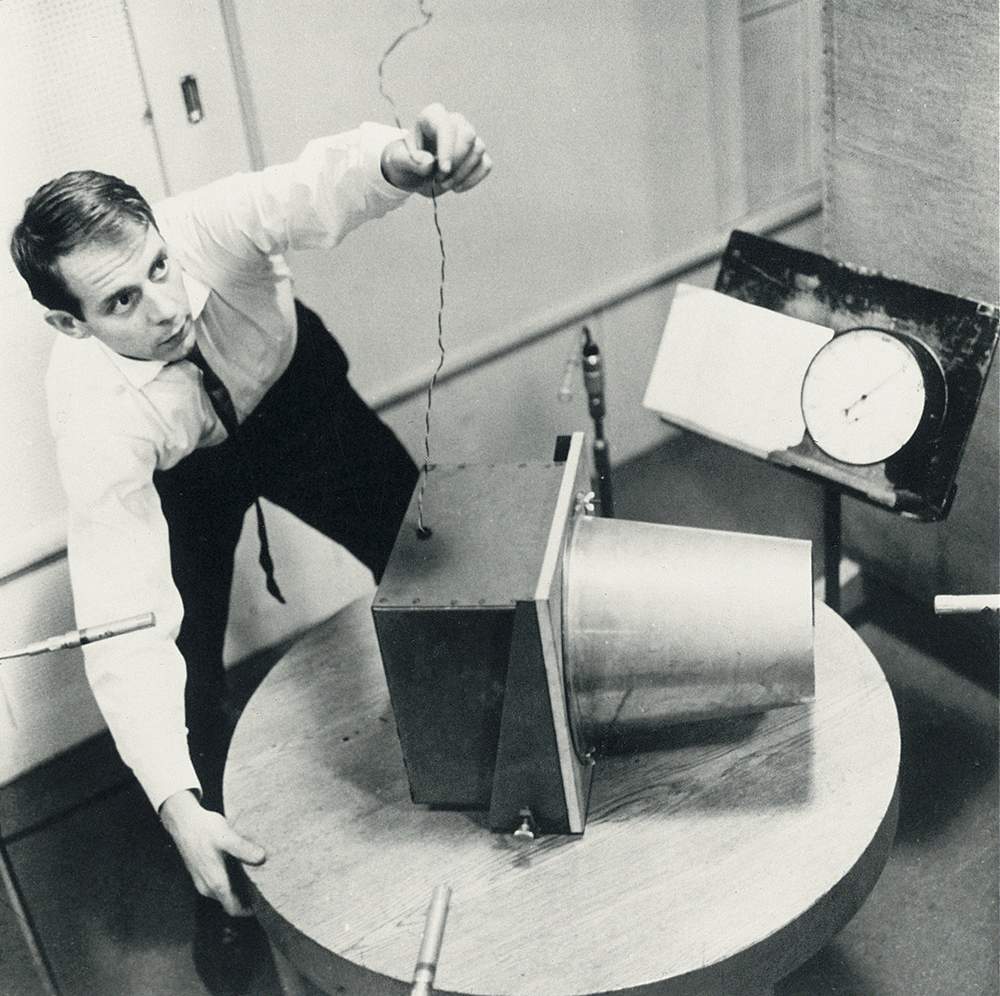

Stockhausen with the directional loudspeaker at the Studio for Electronic Music of WDR Cologne, 1959. © Archive Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik, Kürten

In the studio Stockhausen built a special rotation table onto which was mounted a directional loudspeaker. Arranged in four corners of a square were four microphones connected to a 4 track tape recorder. During playback in performance, this enabled sounds to zoom around the concert hall, to flood from one corner across the space into the opposite corner and for sounds to rotate, spinning dizzily in space.

Stockhausen also composed seminal vocal works in the 1960s. Momente, for mixed choirs, instrumentalists and electric keyboards, was composed, in different versions, between 1962 and 1969. Stockhausen described it as '… practically an opera about Mother Earth surrounded by her chicks.' He always described this work as his most important and his own, personal favourite of all the works he composed.

Tenor Caleb Nelson of Pro Coro Canada explains and demonstrates this fascinating technique

Stimmung, which is performed at the Barbican on Monday 20 November, makes groundbreaking use of overtone singing to mesmeric effect.

From 1977 to 2003, Stockhausen worked on Licht (Light), a vast cycle of seven operas, each named after a day of the week. The scale of this work is breathtaking: a project of lucid vision, total commitment and assured determination.

These operas are not so much vehicles for the musical settings of text, where a libretto unfolds to tell a story, but rather they are a mechanism for integrating the elements of opera - music, text, set, costume, lighting, props, dance, acting etc. - in new ways. Each opera does tell a story with characters interacting dramatically and musically, and the operas fit together to form a chronicle of Biblical magnitude, but music, rather than textual narrative, is the primary structural force.

The Helicopter String Quartet is the third scene from Karlheinz Stockhausen's opera Mittwoch aus Licht (Wednesday from Light). One of the main themes of the opera is flight and this scene came to Stockhausen in a dream. It is the only string quartet he composed

After completing Licht, Stockhausen began working on another gargantuan undertaking: Klang (Sound). This was planned as a cycle of 24 one hour chamber works, each related to an hour in the day. Cosmic Pulses, composed in 2006/07, is the 13th piece in the cycle. Stockhausen was working on this cycle when he died in December 2007; he had completed 21 of the planned pieces.

'He liberated the whole world of sound and this, in turn, has liberated the listener'

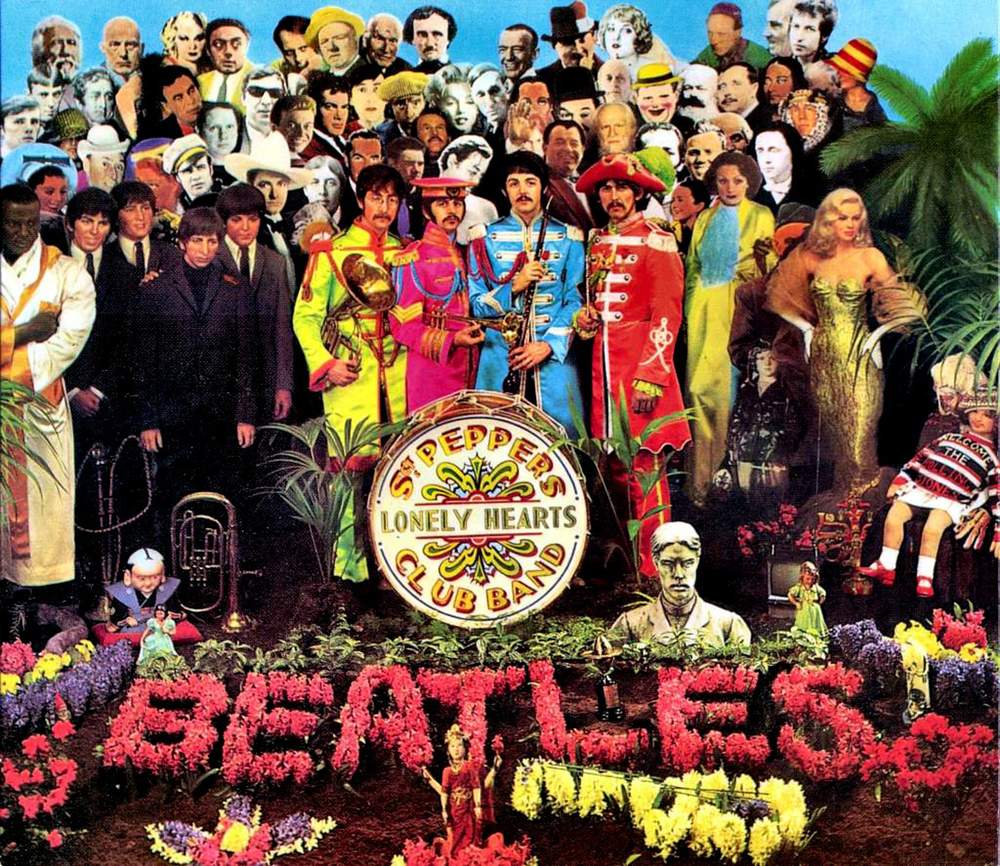

Stockhausen’s work had a profound impact in the late 20th century, from the classical world right through to pop, dance music and hip-hop, from Harrison Birtwistle and Peter Maxwell-Davies to Björk and Aphex Twin. In 1967, The Beatles considered him so significant they included his image on the cover of their LP Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

Cover image for The Beatles' Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Stockhausen, fifth from left, back row

There can be no doubt that Karlheinz Stockhausen was one of the greatest composers of our time. His career spanned more than 50 years and he composed 370 works. He constantly invented new ways of composing and, consequently, he defined, and redefined, what music actually is.

He liberated the whole world of sound and this, in turn, has liberated the listener.

Stockhausen: Stimmung & Cosmic Pulses

For the tenth anniversary of Stockhausen’s death, some of the composer’s closest associates perform two of his defining masterpieces:the meditative, trance-like Stimmung and the earth-shattering Cosmic Pulses.

The concert took place on 20 November 2017 in the Barbican Hall.

About Robert Worby

Robert Worby is a London-based composer, sound artist, writer and broadcaster.

Archive photos and materials kindly provided by Kathinka Pasveer and Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik, Kürten, Germany

All the Stockhausen works mentioned in this piece are available to purchase as part of the official Stockhausen Complete Edition, found at stockhausencds.com