Barbican Guide

May 21

Hello!

It’s such a pleasure to be opening again – we’ve been looking forward to this moment from the minute we had to close our doors due to the government restrictions. Before the most recent lockdown, 95% of Barbican visitors said they felt safe or very safe here, and we have measures in place to ensure you have the safest and most enjoyable time here.

Our major exhibition about the father of Art Brut, Jean Dubuffet, opens on 17 May – keep reading to find a handy explainer about what that term means, and there’s lots of other information about this influential French artist on our website.

The Live from the Barbican broadcasts from the Hall have been a huge success – this month we’re very excited to have This Is The Kit, Shirley Collins, and Paul Weller with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, led by Jules Buckley; and – hurrah! – the London Symphony Orchestra returns for the first time in a year.

If you’re going to watch a movie, you’ll notice our Cinemas have undergone a revamp – do let us know what you think, we’re rather pleased with how they look. There’s a novel cinematic event in Cinema 1 this month. And if you can’t make it to the big screens this time, don’t forget our Cinema On Demand service has a curated selection of films to choose from, and members can watch many of the films for free while the Centre is closed.

A highlight of any visit, the Conservatory reopens this month – definitely worth getting a free ticket for whether you’re visiting for another event or not. Our Head Gardener shares a behind-the-scenes look at how they’ve kept it ship-shape through the last 12 months.

Finally, like many arts organisations, the pandemic has hit our finances hard. If you can, we’d love it if you could give a donation. A huge thank-you to everyone who has done so far. It means we can keep sharing incredible arts from around the world with you. Thank you all for your support.

Disparate, but harmonising

Preparing for a group art exhibition without meeting in person was one of the critical problems facing this year’s Young Visual Arts Group cohort. But they found the challenges brought them together.

Over the last nine months, 14 young artists aged 17 to 25 had regular online sessions with arts industry mentors and Barbican staff. Supported throughout by lead artist mentor, Jordan McKenzie, the group attended online sessions run by Ufuoma Essi, Stephanie Francis-Shanahan, Cadence Kinsey, Ellie Pennick and Antonio Roberts, who helped them develop their practice through advice and workshops. The group is now preparing its exhibition, which will be a fully online event.

Group member Siavash Minoukadeh will be starting at the Royal College of Art in September. He mainly works as an event producer, art writer and curator, and says he’s interested in ‘looking at questions around participatory and community art projects.’

While acknowledging that the group being unable to meet in person has been difficult, he says, ‘The biggest impact of being online-only is the fact we’ve needed to be really clear about our shared aims and themes from early on.’

Fellow young artist and writer, Nefeli Kentoni, is fascinated by the intersections between different disciplines, by the spaces where scenography and philosophy, aesthetics and theatre, filmmaking and poetry meet.

‘It’s impossible to ignore the drastic transformation our lives have gone through during the pandemic. It is also impossible for our creative practice to not reflect that,’ she says. ‘Our realities now lie somewhere between the constraints of our physical, isolated world – behind four walls – and the freedom that sustains the never-ending, collective digital space. This oxymoron produces both an identity and artistic crisis, as our realities feel fragmented and disjointed. I think a lot of our discussions regarding the group’s artistic approach were attempts to reassemble these fragments and/or find ways of dealing with the remains as a community.’

From the start, the group has been exploring an idea of nourishment and growth, and this will be reflected in the exhibition. ‘We’ve been using the metaphor of an allotment where everyone has their own little patch to do their own thing, but we also share a collective responsibility to look after the overall environment,’ says Minoukadeh. ‘Practically, that means that while you might encounter a wide range of media and themes, they can all sit harmoniously together.’

Young Visual Arts Group Exhibition opens from Thursday 20 May.

The Young Visual Arts Group is just one of a broad range of programmes we run for young creatives. To find out more and give a donation to keep this important work running, see barbican.org.uk/take-part

Classic pop

Crossing genres with ease, Jules Buckley is renowned for redefining the role of orchestral music. His latest project sees him working with one of the defining figures of British pop – Paul Weller.

‘I’ve done two projects so far in my career where I’ve started and then thought “How the fuck am I going to choose the songs?” – and that was Quincy Jones and Paul Weller.’

With a CV spanning 70 albums, a Grammy Award, and a reputation for crossing genres, Jules Buckley is no stranger to arranging for some of the biggest artists in the world. But even the co-founder of genre-smashing ensemble the Heritage Orchestra admits to feeling a little daunted at the prospect of his latest project with the BBC Symphony Orchestra.

Paul Weller’s first live concert in two years will see the Modfather joined by the orchestra for an exclusive performance of tracks from his brand new album, plus back catalogue highlights that demonstrate just

why he’s been charting for five decades.

With Buckley at the helm, you know this will live up to expectations. He’s known for bringing a touch of Ibiza to the Proms with his Heritage Orchestra and BBC Radio 1 DJ Pete Tong, as well as working with grime acts such as Stormzy and Wretch 32 as Conductor of the Metropole Orkest, with whom he performed the 2016 BBC Prom with Quincy Jones. Since he joined the BBCSO as Creative Artist in Association in 2019, he’s developed some boundary-breaking projects, including the unforgettable concert with Lianne La Havas here in February 2020.

Buckley tells us that while his earliest memories of Weller’s work came from hearing The Style Council on the radio as a child, his real appreciation came when solo album Stanley Road was released in 1995.

The music that’ll be performed at this concert was chosen through a gradual process. Buckley began by listening to listening to everything Weller had released. ‘I think we were moving flats at the time and I had to sand the floor in my old flat in order to get the deposit back. So I spent days just listening to all of Paul’s albums as I sanded, making notes on my phone of any title that I thought really would lend itself to being placed in this setting.’

Then, over the course of a few video calls, he and Weller honed the list. ‘There was a feeling that we wanted to really focus on the latest work. That was very important because Paul, as an artist, is always moving forward. We didn’t want the gig to feel like a retirement concert. But at the same time, Paul’s got so many killer tunes that we had to bring in a lot of the classic tunes too. So we’ve ended up with a “mix tape” of music that takes the audience through the old and the new.’

Among the new material will be Weller’s new album, Fat Pop, recorded during the first lockdown in 2020.

‘I’ve heard it and it’s a phenomenal album,’ says Buckley. ‘The musicians playing on it, the production choices, the lyrics... Paul is up there. He’s not got many peers.’

Paul Weller, Jules Buckley & BBC Symphony Orchestra takes place on Saturday 15 May.

‘We’ve got goosebumps

thinking about it’

After a 14-month absence, the London Symphony Orchestra returns to our Hall under the baton of Sir Simon Rattle. The musicians say they can’t wait.

The popular Live from the Barbican series brought music from our Hall to your living room for months. Yet while our resident orchestra has regularly performed live streams from St Luke’s, its absence from the Barbican has been tangible.

Cellist Jennifer Brown joined the LSO aged 26 in 1982, just two months after the Centre opened. She describes the Barbican as like ‘home’ for the LSO members. She and horn player Angela Barnes, who joined in 2005, usually share a dressing room. Both say they’ve found the time of the pandemic extraordinary.

‘Over the last year, I’ve had the time to practice every single day – which is probably more than at any time since I was a student,’ laughs Brown.

And, while there have been frequent rehearsals, recordings and livestreams, they both have missed performing in front of a live audience.

The pair say live streaming brings the same pressures for accuracy compared with being in a recording studio when multiple takes are possible. ‘It’s about living in the moment,’ says Barnes. ‘And in some ways, the microphones and cameras feel a bit like a substitute for a real audience.’

However, the prospect of performing in front of people again is tantalising for the musicians. ‘I’ve got goosebumps just thinking about it,’ says Brown. Barnes adds, ‘It’s going to be incredible. It’ll feel joyful and energising on both sides. Even if there are just 500 people in the Hall, I hope that firstly they feel safe, but also that they’re as excited as we will be. We just can’t wait to get back to making live music.’

Limited numbers of performers allowed on the stage mean there will be musical arrangements that some people may not have heard before, which will be interesting for performers and listeners.

The first concert back will be a live streamed performance of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde – the composer’s poignant song cycle contemplating the transience of life, which feels particularly apt following the ordeals of the nation over the last 12 months. Written in his final years, shortly after he was diagnosed with a heart condition, and following the death of his daughter, it travels between moments of joyful lightness and dark melancholy.

Led by Sir Simon Rattle, the orchestra will be joined by mezzo-soprano Magdalena Kožená and tenor Andrew Staples for what will be a long-awaited return to the Hall.

After that exciting return, 18 May heralds the day when finally, audiences will be able to see one of the greatest orchestras in the world in person, as we welcome music fans back into the Hall.

Why being a Patron is important to me

Architect Lucy Musgrave tells us why she supports our work.

When she moved to London in 1984, aged 18, Lucy Musgrave fell in love with the City on late-night bike rides after finishing her waitressing shift. Since then, she’s helped shape the landscape of this most ancient part of London – she was involved in setting the Area Strategy for the Barbican and Golden Lane Estates and the vision for Culture Mile.

The founding director of Publica is a Barbican Patron and one of the board members. And while she’s long been a fan of the design of the building, her deep relationship with the events that happen here stems back to a panicked winter.

‘I’ve got four children, so life has always been hectic,’ she recalls. ‘I used to live in the Barbican, and one Christmas I realised I hadn’t bought anything for my husband. So I ran down to the Arts Centre box office and booked one event for every month that year as his gift. It was a long time ago, and I didn’t know in any great depth about classical music at the time, but the first event was a concert by the London Symphony Orchestra performing Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms. We were transported. That concert changed our lives. Every Christmas, I still buy him the same thing.’

So last year, Musgrave felt the Centre’s closure due the government advice, particularly keenly.

‘I was heartbroken to miss concerts such as Wynton Marsalis and the LSO,’ she says. ‘But we did enjoy the online offer. What [Head of Music] Huw Humphreys and the team is doing with Live from the Barbican is amazing.

‘I also watched the Michael Clark online walkthrough. I love him – one of my highlights of 2017 was his to a simple rock'n'roll song.

‘Being able to see so much content on the Barbican website is wonderful. There’s been a lot of really careful, creative and resourceful thinking about the connection with the audiences, performers and companies.’

However, there’s a wider reason why Musgrave feels supporting our work is important: ‘In terms of culture, the significance of what the Barbican does in the City is profound, across art forms. But also, in terms of its outreach work through Beyond Barbican and Creative Learning, how it democratises culture and promotes better inclusion, its engagement with young people, and much more – these are all reasons why I wanted to support the work of the Barbican as a Patron.’

Learn more about becoming a Patron and other ways to support our work at barbican.org.uk/support-us

© Amandine Alessandra

© Amandine Alessandra

A guide to Jean Dubuffet and Art Brut

French artist Jean Dubuffet coined the term Art Brut. But what does it mean and why was it important to Dubuffet’s work? Curatorial assistant Charlotte Flint explains.

‘Art Brut’ refers to art made by individuals working outside of the established cultural mainstream. In English it tends to be translated as ‘Outsider Art’, which is the phrase Roger Cardinal used for his book on the topic in 1972. By the end of his life, Dubuffet had collected more than 5,000 artworks by these artists, who were a powerful source of inspiration for him.

Our exhibition Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty features the work of sixteen Art Brut artists alongside Dubuffet’s work, demonstrating the important role they played in shaping his thinking on what art could be. Let’s delve into this history of the term and what Art Brut meant to Dubuffet.

When did the phrase ‘Art Brut’ first

emerge?

The term ‘Art Brut’ was first used in a letter

written by Jean Dubuffet to his friend René

Auberjonois on 28 August 1945 following a

visit to Switzerland to see the work of artists

marginalised from mainstream culture,

including patients in psychiatric care. Literally

translating to ‘raw’ or ‘crude’ art Dubuffet

explained: ‘We mean by that term works done

by people uncontaminated by artistic culture,

works in which the sense of mimicry, contrary

to what happens among intellectuals, plays

little or no part, with the result that their makers

draw all… from their own being and not from

hangovers of classical or fashionable art’.

Although this was the first time the term was

used, Dubuffet had a longstanding interest in

less conventional artworks and uncommon

objects. This passion was evident from

childhood, when he turned his bedroom

wardrobe into a ‘museum’ where he displayed

unusual things he’d found such as minerals,

fossils, insects and nuts.

Why did Dubuffet devote so much

time and energy to researching and

promoting this work?

As a young artist, Dubuffet felt disillusioned

with the academic art popular in France and

wanted to explore a more ‘authentic’ artistic

language that conveyed the grittier reality

of being alive. He was drawn to the work

of untrained artists who existed beyond the

accepted cultural mainstream and felt that

the work produced by graffitists, tattooists,

self-taught artists, spiritualists, people in jail,

and individuals in psychiatric care (to name a

few) was truer and more vital than anything on

display in art galleries or museums at the time.

Throughout his life Dubuffet poured a

phenomenal amount of time, energy, and

money into collecting and researching Art

Brut, and took advantage of his own acclaim

to showcase the work of these lesser-known

artists. It was a labour of love fuelled by

his unwavering belief in the importance of

these artworks; one donor to Dubuffet’s

collection recalled: ‘it was astonishing to see

how much satisfaction (the artworks) gave

him… he became feverish. It was truly the

greatest pleasure one could have granted

him: to bring in new things, new creations’.

Were all the artists paid for their work?

We know that in some instances Dubuffet

directly corresponded with artists and

arranged to purchase a work for an agreed

price. For example, in 1948, Dubuffet bought

artworks directly from Miguel Hernandez

(1893–1957), Pascal-Désir Maisonneuve

(1863–1934) and Henri Salingardes (1872–

1947) and the sales were documented in

ledgers kept at the time. More frequently,

artworks were gifted to him. Sometimes

these were presented directly from the artist

– there are records of the artists Gaston

Chaissac (1910–64) and Joaquim Vicens

Gironella (1911–97) donating their works to

Dubuffet. More frequently psychiatrists in

institutions gave work to Dubuffet that they

thought would be of interest to him, and that

would be well cared for in his collection.

In these instances, patients did not receive a

fee and were not aware that their work was

being shown in public. Dubuffet was known

to send the artists gifts such as paint, brushes,

cigarettes and small amounts of money.

Displaying the work of psychiatric patients

without their knowledge raises important

ethical questions about consent and medical

confidentiality, and we acknowledge that

this is a problematic element of Dubuffet’s

collecting practice. Art Brut historians similarly

recognise the challenging nature of these

donations but have reached a consensus

that doctors at this time were acting in good

faith and that many had prolonged periods

of engagement with their patients and

enormous admiration for their artwork.

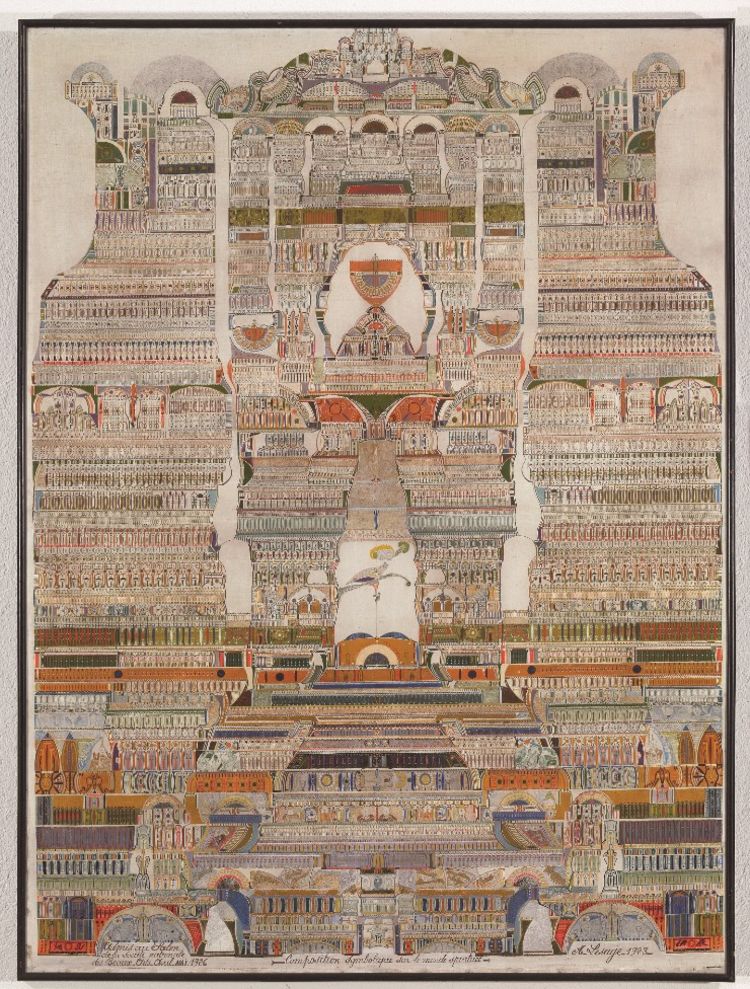

Augustin Lesage, Symbolic Composition of the Spiritual World (Composition symbolique sur le monde spirituel), 1923, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, Photograph by Claude Bornand, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

Augustin Lesage, Symbolic Composition of the Spiritual World (Composition symbolique sur le monde spirituel), 1923, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, Photograph by Claude Bornand, Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne

How much do we know about the artists

in his collection?

The amount of information available varies

from artist to artist. For artworks produced

by some psychiatric patients, often very little

of their biography is known. However, in the

cases of Adolf Wölfli (1864–1930) and Aloïse

Corbaz (1886–1964), two artists who were

living in psychiatric hospitals, there are much

fuller historical records because their doctors

encouraged and documented their artistic

practice. Dubuffet was a prolific letter writer

and his correspondence with artists was

carefully archived. For example, Dubuffet and

the artist Gaston Chaissac wrote more than

440 letters to each other over twenty years,

and as a result we have a much fuller account

of Chaissac’s life and artistic output.

Did Dubuffet’s collection of Art Brut

only include work by men?

No. Some of the earliest acquisitions that

Dubuffet made were by female artists and

he continued to collect work by women

throughout his life. In a letter to Michel

Thévoz, a former director of the Collection

de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Dubuffet wrote:

‘it has always seemed to me that cultural

art is invented by men for men and women

are hardly able to do it. But as regards Art

Brut; I am amazed to state the contrary:

women [are] much more adroit, more at ease than men. Probably because [they are]

less conditioned by cultural arts norms’.

Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty takes place 17 May–22 Aug

The structure of silence

Director Philip Gröning lived in a monastery for six months to make Into Great Silence. A near-silent meditation-like experience, the film was released in 2005, but its themes of isolation resonate strongly today.

Being shown as part of our Architecture on Film series, Into Great Silence is extraordinary. Over its almost three hours’ duration, you’re transported to a place of quiet contemplation, rhythm and routine. There’s no music other than monastic chants, no narration, no interviews. The effect is that rather than being about the monastery, the film becomes a monastery itself.

‘What originally fascinated me was that I view a monastery as a machine through which the handling of time is transformed,’ says Philip Gröning. ‘Similarly, as filmmakers, the mode of expression we have is time: how strictly we handle it for the audience is what sets cinema apart from all other mediums.’

Time is something that has interested Gröning for many years. Into Great Silence is very much a mediation on our experience of the fourth dimension. And in a meta way, the film’s creation was a decades-long journey.

‘I had the idea when I was 24 and had just finished film school,’ recounts Gröning, whose current work is more focussed on visual arts than Cinema – he recently exhibited a huge VR project about Oktoberfest in Shanghai and Munich. ‘I won an award for young filmmakers and was proving to be successful. But [fame/success] took up all my energy and I wanted to get out of the industry and retire to write novels or something.’

A Roman Catholic upbringing led him to seek out Orders of monks that were completely silent, but he discovered there weren’t any. However, he did learn of three that are ‘pretty much silent’, the Carthusians being one of them. ‘I wanted to see what it was like living in these conditions and thought I should make a film about it too.’

Inside the Monastery

Inside the Monastery

Perhaps unsurprisingly for devout people who shun the outside world, there wasn’t much enthusiasm among the monks for his idea. But, after being turned down by many monasteries, finally the abbot of the Grand Chartreuse in the French Alps invited Gröning to stay for two weeks. ‘I knew immediately that this was the place I wanted to film,’ he remembers. ‘But they said, “it’s not the right time just now, but maybe in ten years’ time”.’

Laughing now, he recalls that his 24-year-old-self found it almost impossible to conceive of making progress on something that far in the future. So, he continued creating, making films such as The Terrorist (1992), Philosophie (1998), expecting nothing further to come of his idea. But he stayed in touch with the abbot. ‘I liked him a lot. Every four or five years I would travel to the monastery and talk to him – I found him very philosophical and trustworthy.’

Then, one day in 2000, at 7am, he got a call from the monastery. It was the administrator, asking if he was still interested. It had been 16 years.

‘I hadn’t even really been thinking about it. Perhaps that’s why I got the opportunity – that I’d stopped talking about it with the abbot. He trusted me because I didn’t talk to him about it, and because he saw the films I was making. I think he saw that I had a very serious approach to my work.

‘When he finally gave me permission, he’d known me for 17 years. I’ve heard that all the big French filmmakers had wanted to go to the monastery – but they wanted to think about the film, not the philosophical idea of being in a monastery; they wanted to observe the monks, almost as if they were strange creatures.’

The void

So Gröning decamped to the Alps to film: for six months in total – four during spring and summer, followed by two shorter phases in the winter. He lived as a monk, occupying a cell as they do, and filming daily life. The only condition they imposed on him was that he was not to use artificial light.

‘When I arrived, I had a feeling of there being a huge void,’ he recalls. ‘It’s what anyone would experience – we spend so much time pushing to have our life filled with things that distance us. Then suddenly you’re there in these beautiful surroundings, with an incredible view from your room, but you don’t speak to anyone. The only contact you have with others is going to church.

That was very difficult, I thought 'what am I doing here?'

I didn’t move into my cell for a week because I thought it was so perfect – I didn’t feel it was right that I was there. So, I just started shooting the empty cell from outside, and lived in a different room.’

Slowly he adapted. And after time, he found a great joy in his experience. ‘There’s a real pleasure in not worrying what you’re going to do each morning. As an artist you have to figure out “what am I doing” every day, but that was already decided for me at the monastery because they do the same thing every day. I felt very at home there.’

Here, we see some of the monks in the film

Here, we see some of the monks in the film

He says the most interesting thing he noticed was how his perception of time changed. It hit him after a moment of despair. He’d taken the same shot of the cloisters with the sun changing on so many occasions and thought to himself he couldn’t bear to take another similar view. But he resisted the temptation to go into the village to find new shots – because the monks don’t have that luxury and he wanted to have – and reflect – an authentic experience.

‘After a while I started to notice the presence of objects and the things that accompany us – their own journeys through the years and centuries; for example, a stone was formed millions of years ago.’

It was this appreciation for the minutiae of daily life, of noticing everything’s progress through time that instilled a sense of calm in him. And so when it came time to leave, he was very sad.

‘The sheer synchronicity of waking up to the sound of the bell and having a moment before going to church, during which you light the little fire in your cell; you look out of the window and see the fires being lit in every other cell. It gives you a sense that everyone is doing the same thing at the same time without being in communication with one another. There’s a sense of community – a community of hermits.’

The film was released in 2005 – 21 years after its conception. It’s won many awards, including a special jury prize at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival, and Best Documentary at that year’s European Film Awards. But more importantly to Gröning, the monks who saw it loved it. One even gave him awooden statue that looked like an Academy Award wearing a cassock. The director says that’s the prize that meant the most to him.

To watch the film is a transcendental experience, and one you’ll probably never encounter in a cinema again. Without words, it invites you to ask questions of yourself, of the way our society operates, of our relationship to objects, and to time.

Ultimately, as Gröning concludes: ‘People ask who the main character is, and the answer is the audience, because the main character in a monastery is the person who will be changed by the monastery.’

Into Great Silence takes place Sun 23 May

Architecture on Film is curated by the Architecture Foundation in partnership with the Barbican

Unintentionally prescient music

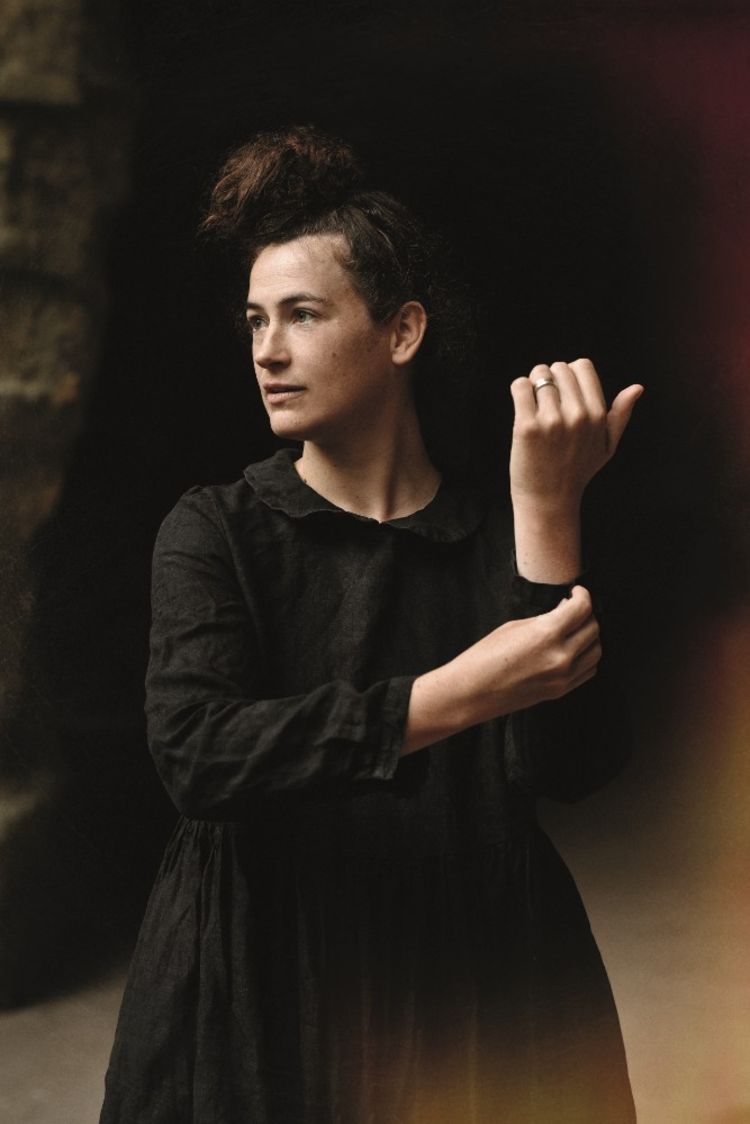

Art often mirrors life – but sometimes it can also predict the future, as singer-songwriter Kate Stables discovered.

A very spooky feeling crept up on singer-songwriter Kate Stables as she mixed This Is The Kit’s fifth album, Off Off On.

She’d written the songs over the previous 18 months, but as the final mixes were taking shape, the first wave of the pandemic hit – and suddenly, her lyrics took on a whole new meaning.

‘Suddenly, the world was different, and my lyrics mention things like coughing, being in hospital, stopping and starting.’ She shakes her head. ‘Yeah, it was very weird.’

The songs were written mainly on tour – either with This is The Kit or solo with The National. Stables says being away from home helped because isolation and space are essential for her writing process; she’d been thinking about the state of the world (‘because even before Covid, things were a bit of a mess’).

‘Humanity is a long timeline, and it’s easy to feel frustrated and worried about the future, so I wanted to find hope in that, not wanting to believe everything is screwed – there’s a reason for hope, solidarity, and sticking at things together.’

She says she also went through a period of self-reflection, trying to recalibrate the way she approaches certain things. ‘As much as we have to work on the outside world and community, we have to do that internal work too and allow for personal growth.’

After it was released, critics seized on the connection with what the world was experiencing at the time. Many picked up how Off Off On was a neat summary of our stop-start lockdown experiences; Elisa Bray in the Independent wrote: ‘The themes too, of resilience and starting again (‘Started Again’), homesickness, needing space, and the perennial question of the work/ life balance (‘Slider’), love and solitude (‘Shinbone Soap’), and anxiety (‘This is What You Did’) could not be more pertinent.’

How does it feel to have people see your work through a completely different prism than intended?

‘This always happens with everything you make as an artist,’ says Stables, who was nominated for an Ivor Novello award following the release of the band’s last album, Moonshine Freeze, in 2018. ‘Whatever you present to the world will be seen through people’s individual goggles and through the eyes of the current times. Even when I’m looking at my own work, I can’t help but see it through that lens.

‘I can’t remember the exact quote, but Alan Bennett said that all writers at some time or another would encounter this experience of “predicting the future”. When you’re working with ideas, words or language, funny coincidences happen. Some people might explain it in cosmic universe terms; others might consider it probability. ‘

This is the Kit: Live from the Barbican takes place on Sunday 30 May.

Keeping our tropical paradise

in ship shape

As we reopen this month, one of the attractions that’s bound to be popular is the Conservatory. Head Gardener Marta Lowcewicz explains what it’s taken to keep this oasis looking its best over the last year.

Housed under 23,000 square feet of steel and glass, the 1,500 species of plants and trees of our Conservatory require regular care and attention. So Head Gardener Marta Lowcewicz and her team have been doing their best during the challenging on-off-on rhythms since March last year.

‘We’ve had to adapt in order to follow government guidance for our own safety. The two of us have been working over five different shifts to keep caring for the plants – which have to be watered because it’s a garden under glass and the rain can’t get in – and the fish and other wildlife, which have to be fed.

‘Over the summer, the Conservatory was open to the public every day, so we tried to catch up on some of the jobs we couldn’t do when we had to be at home. But it’s almost impossible when you lose a whole year of planting.’

Over nature’s quieter period, winter, Lowcewicz and her colleague Sarah Fox carried out pruning and other maintenance to prepare the plants for their spring burst of growth. ‘The Conservatory is a constant work-in-progress,’ she says. ‘Unlike when you come to see an exhibition, concert or play and you see the end result, this is more fluid, more alive.

‘The plants here may be tropical and temperate, but the principles are the same as a garden at home – you have to find the perfect spot for the plants. Maybe it doesn’t like the place you thought it would, so you have to move it; it’s a little bit of trial and error, based on your knowledge. We have to think about creating an environment that’s good for the plants and aesthetically pleasing for everyone.’

As well as the lush foliage of the main floor of the building, there’s also a succulents and cacti room on the east side. It’s definitely worth a visit. You’ll also find an overwintering collection of cymbidiums (cool house orchids).

For perfectionist Lowcewicz, preparing to readmit visitors has been an awful lot of work. ‘While in my head there’s always things I’d like to do, or something I want to be updated, I think we’ve done our best in getting the Conservatory ready for reopening,’ she says.

The Conservatory is open from Monday 24 May.

Inspired by our architecture

Get yourself ready for our reopening with this exclusive Barbican architecture range, available in our Shop and online. Our design team took inspiration from the classic motifs of the Barbican estate – the barrel vaulted roofs of Frobisher Crescent, the balconies and the sky-piercing tower formations.

Barbican Architecture Collection Thermal Flask

This 450ml thermal stainless steel flask has an added tea infuser function, so you can bring your brew with you. It’ll keep your cuppa hot in the morning, or cool when you want an afternoon iced tea.

Black Barbican Architecture Collection T-shirt

Wear your love for the Barbican on your chest, with this simple but elegant black and white T-shirt, made from 100% cotton.

Barbican Architecture Collection Pouch

A handy zip-up pouch, perfect for storing your stationery or toiletries. Design inspired by the Brutalist architecture of the Barbican.

Members get 20% off until the end of May.

Barbican Architecture Collection Thermal Flask

Barbican Architecture Collection Thermal Flask

Black Barbican Architecture Collection T-shirt

Black Barbican Architecture Collection T-shirt

Barbican Architecture Collection Pouch

Barbican Architecture Collection Pouch

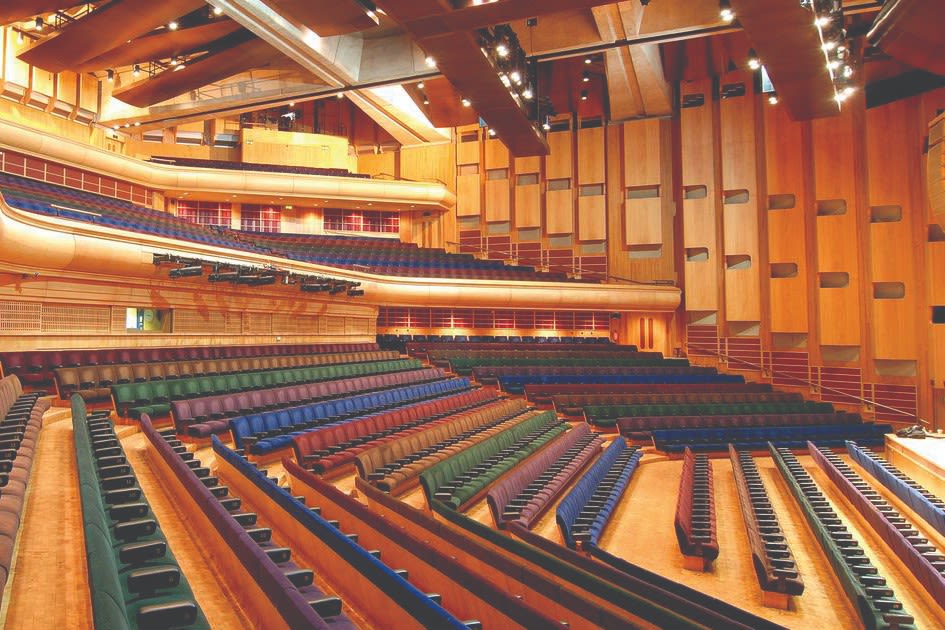

The Barbican Hall

The Barbican Hall

St Giles Cripplegate

St Giles Cripplegate

The Terrapin Pool

The Terrapin Pool

My Barbican: Ed Maitland Smith

Our Communications Officer for Music shares his favourite places in the area.

Balcony of the Barbican Hall

I’d been coming to see music at the Barbican for years before I ever worked here and always loved sitting in the balcony. I honestly don’t think there’s a more democratic concert hall than the Barbican in terms of sight lines, acoustics, and, let’s face it, leg room and the balcony really reflects that. Being able to sit there quietly and listen to rehearsals now that I work here is a real perk of my job that I can’t wait to do again when we’re back in the building.

St Giles Cripplegate

The Barbican seems to have so many secrets that are common knowledge to almost everyone except me… It took standing next to the large plaque throughout a performance by Missy Mazzoli and Kelly Moran in St Giles Cripplegate, (the medieval church across the Barbican Lakeside) for me to discover that the poet John Milton, of Paradise Lost fame, is buried on the site. Despite the modernity and the brutalism, the area is laced with history, and St Giles is a perfect example of that. I’m also a sucker for a medieval church.

The Terrapin Pool

I went to a wedding in the Barbican Conservatory when I was a kid, about 23 years ago. It was probably my first Barbican interaction… Ashamedly, I don’t think the place made much of an impact on me then, aside from the pool of terrapins next to the Arid House which is still there today. I don’t know the lifespan of a terrapin but I like to think it’s the same gang.

With thanks

The City of London Corporation,

founder and principal funder

Centre Partner

Christie Digital

Major Supporters

Arts Council England

Esmeé Fairbairn Foundation

SHM Foundation

Sir Siegmund Warburg’s Voluntary Settlement

The National Lottery Heritage Fund

Terra Foundation for American Art

UBS

Wellcome

Corporate Supporters

Aberdeen Standard Investments

Allford Hall Monaghan Morris

Audible

Bank of America

Bloomberg

Derwent London

DLA Piper

Howden M&A Limited

Leigh Day

Linklaters LLP

Morrison & Foerster

Pinsent Masons

SEC Newgate

Slaughter and May

Sotheby's

Taittinger Champagne

UBS

Trusts & Grantmakers

Andor Charitable Trust

Art Fund

BFI

Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation (UK Branch)

Cockayne – Grants for the Arts

John S Cohen Foundation

Creative Europe Programme for the European Union

Edge Foundation

Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

Europa Cinema

Stavros Niarchos Foundation (SNF)

The Harold Hyam Wingate Foundation

The Henry Moore Foundation

The London Community Foundation

The Mactaggart Third Fund

The Nugee Foundation

Tom ap Rhys Pryce Memorial Trust

Barbican Cinema has been supported by

the Culture Recovery Fund for Independent

Cinemas in England which is administered

by the BFI, as part of the Department for

Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s £1.57bn

Culture Recovery Fund supporting arts and cultural organisations in England

affected by the impact of COVID-19.

We also want to thank Barbican Patrons, donors to Name a Seat, Members, and everyone who has supported the Barbican by making a donation.

To find out more, visit barbican.org.uk/supportus or email [email protected]

The Barbican Centre Trust, registered charity no. 294282