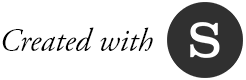

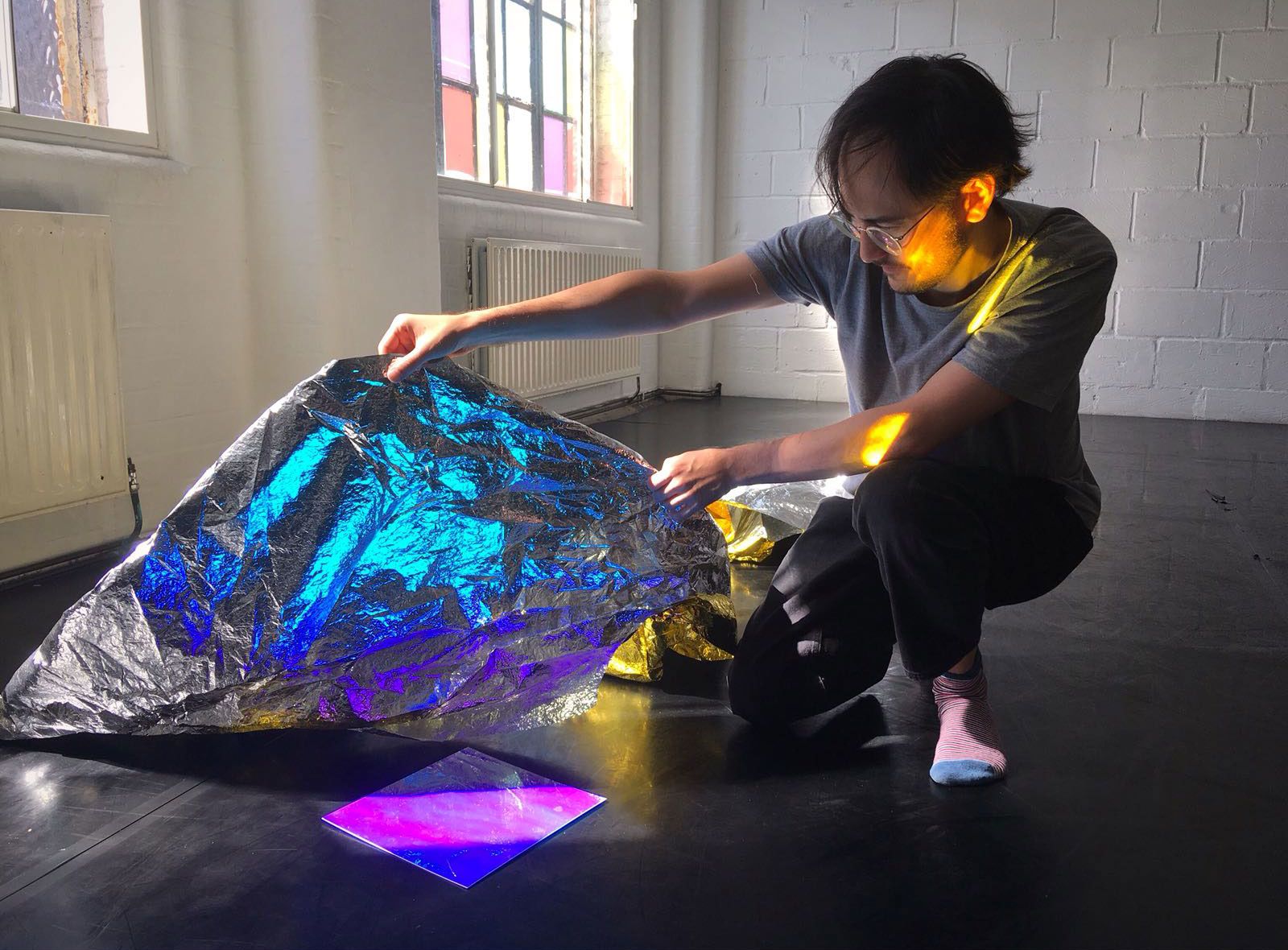

Alan Fielden with JAMS:

Marathon

What might a play for a generation living in the digital age look like? JAMS discuss the creative process behind Marathon, and winning The Oxford Samuel Beckett Theatre Trust Award 2018.

Experimental storytelling, live music and pyrotechnics - what would a play for a generation living in the digital age look like?

Winners of this year's Oxford Samuel Beckett Theatre Trust Award 2018, JAMS (comprising Jemima Yong, Alan Fielden, Malachy Orozco and Sophie Grodin), wanted to find out with Marathon, a project where the storytelling is disrupted, never fully taking shape, as our narrators try to recall an event.

Marathon is the story of a man on the front line of a conflict between two countries, who is told by his general to relay a message to the king:

‘We’ve lost the war, the enemy is coming.’

The journey he takes and the people he meets along the way lead him to question his faith in the mission.

We talk to the members of JAMS about their theatre-making process, the story behind Marathon, and what advice they would give to other theatre makers.

How did it feel to win The Oxford Samuel Beckett Theatre Trust Award 2018?

Alan: I was deeply nervous, and I was scared when I got the call that we’d made the shortlist. I went crazy: I started jumping around and whooping when I found out. When we actually won outright; I felt relief, I was really proud of the show at that point. Winning was the wonderful, great, big, red cherry on a cake that already tasted quite good.

Sophie: I wanted to stay focused on what we had to do. I didn’t let myself imagine that we could win. If I focused on winning, I was worried that it would take my focus away from what we had to do - make a really good show. I felt really excited because it was unexpected for me.

The best feeling was that people we didn't know, who hadn't been in our brains or close to our thoughts had now watched our work, and liked it. That was a big recognition.

Jemima: For me, it felt like a game; we had to keep playing to go through levels. I was always engaged in this ‘game’ and if I was allowed to, I would continue playing. When we won, it felt more like relief than ‘oh my god, I’ve won the lottery!’ because I view this as an opening to the next level.

Winning, being shortlisted, handing in the application – these were all pit stops in a longer process.

Alan: It’s like when you’re Sonic the Hedgehog and he's drowning and then he gets a bubble of oxygen. That’s what it felt like.

Jemima: The sharing was a highlight for me with eighty or so people in the audience. It was encouraging and touching to see people who had taken time off to come and watch us in this small, private sharing. It felt like communal theatre, everyone being present at this live event.

Mal: The euphoria fades when you realise how much time you have. I remember tweeting that we had 40 weeks to put a show on. Wow. Ok. It’s amazing and it’s an honour. Everybody is watching so it’s also like f***!

What has been your creative process when working on Marathon?

Jemima: Alan had the idea back in 2016.

Alan: It was warm, so summer. Sophie had come over for a weekend, we chatted on the South Bank. I had ideas floating around from disparate sources. I remember talking to Mal and Jem at that tower in Elephant and Castle, sharing some ideas. Then tinkering away in my head.

Fortunately, our friend who works at the University of Worcester, Dan Somerville, established a residency, and made space for us to be at a Children’s Literature Festival tent when it wasn't being used. It was then that we planted the seeds for where we are now. We were there for 3 weeks. That was the autumn / winter of 2016. Our process has developed since then, but when we look at early footage of us, looking back at that time– it’s clear that stuff was the baby of what we’re doing now. It’s just grown.

Sophie: What was the baby?

Alan: I remember sitting with Mal on a stage, describing a scene where a messenger meets two deserters, one of whom has had his legs blown off, and then there we were in those roles, performing the scene. That switching between describing and enacting...and how foggy storytelling can get, questions of narrative authority, of total belief and then absolute disenchantment, talking about the story being just as important as the story....that was all there in Worcester.

Mal: Our common identity - as a company - comes from ROOM (2012). Other collaborators, especially Annabelle Stapleton-Crittenden, have influenced this process. In ROOM, we use language, and live foley sound to create images. Then, we let audiences’ imagination play an active part in creating the content with us in real time. That has always been interesting to us: What if we took ROOM and put it on stage? We’d never been on a stage as a group before.

Jemima: ROOM was inspired by computer games and choose your own adventure books. It was a performance in which one audience member takes part at one time. They are blind-folded, and we take them into a world through dialogue and through foley sounds. They actively have to participate and choose what happens to them.

'Instead of doing that thing why don’t you talk about that thing as if it already exists'

Alan: I was inspired by Borges. He said something along the lines of:

Why waste the time and energy writing a big book about some ideas when you could write about that fictional book, and in doing so, save time, but infer everything you need to infer.

Alan: This idea was quite interesting, also quite amusing to us. Another thing that influenced us was the general atmosphere of the world at that time: Brexit, the Trump campaign, the concepts of ‘fake news’ and 'truthness' were first being talked about in 2016. This idea of suggesting things and pointing towards things that may not be true, that were completely fictional...

Jemima: We were playing a lot with narrative authority and the distribution of narrative authority in play. This idea that there are lots of different narratives taking you in different directions. Changing where the narrative authority lay in different theatrical situations was interesting to us.

Alan: There’s a phrase that came up in our process, 'quantum narrative', the idea that a narrative can change depending on it being observed, and who's observing it...

'This idea that there are lots of different narratives taking you in different directions'

Sophie: As the show isn’t coming from a text that’s been written, we are making the show as we go alongside our own lives, so that in a way what's actually happening in the world and what’s happening with us in the world can and is allowed to be part of the work.

The research for the show has become part of the way we work, move and think.

It becomes an organism that starts having its own life. We started to see connections between lots of different things, how the news and how stories or how small bits of information that we get on a daily basis start to creep into the work. We become open to influences and we all need that time to get to a place where you’re open to influences.

Malachy: When you said that you’re like an organism growing, the image that I had was kind of like a dandelion or flower that’s out there blowing in the wind and is openly receptive to ideas whilst growing at the same time.

'We simply don’t know how to live with difference'

What do you want audiences to feel and take away from Marathon?

Jemima: I hope audiences come and are receptive. That they open up and are as open and as porous as the work is. The work needs their active imagination to work. I don't think they need to worry about necessarily 'getting it'.

Sophie: Some work can feel alienating when you don’t feel like you have an entrance into the work. But with Marathon, it's the story of a messenger trying to relay a message to the king, telling him that the enemies are coming, the war is lost.

You come into work with that story. The way we do the show has nothing to do with following that story. But the story is still present. We used characters almost like pillars - what happens between them is quite abstract and absurd but audiences have something to hold onto. This potentially creates a kind of stability in something that is quite chaotic.

Alan: Sammy B (Samuel Beckett) used to say something about wanting his work to operate on your nerves rather than your intellect. That's always meant a huge deal to me.

The modern world feels like a place with a lot of anxiety, fear, confusion and doubt, worry. We aren't making a show to explain any of this or to change the world in some grand systemic way.

But to speak to that part of a person that says, ‘I feel scared’ and here we are… four people dealing with something, saying ‘I acknowledge that feeling in you’.

Seeing the show and feeling that some part of you is recognised by the show – this is a beautiful feeling, I think.

'Feeling that some part of you is recognised by the show – this is a beautiful feeling, I think'

Sophie: You also spoke about repair, about people coming together to go through emotions, fear and confusion. Looking to each other and thinking about ways of approaching things. Not coming up with answers necessarily, but at least you’re moving together in a way and coming up with something.

Alan: Yeah, we've talked about the dramatisation of repair. What makes this show hopeful is that there are four people in a difficult position and the one thing they're relying on is a degree of repair and cohesion, or the knowledge that at least they might rely on each other.

Sophie: Is it necessary to rely on cohesion, though? Can you find a place where you are not in a dangerous position even if something isn’t cohesive? Even if you’re not on the same page the whole time?

We’re so used to moving around in physical or digital spaces surrounded by people who agree with us. We are not used to what it means to debate or what it means to not agree but still be friends, be around someone with a different political opinion to us, who doesn’t agree with us and continues to be friends, still be respectful and still work together. This is a really big problem in the world we live in. We simply don’t know how to live with difference.

Today there are not a lot of public meeting places like the church, the pub, the community house used to be. They were places where you could share the same space with people who are different to you. For us, the theatre can be one of those places, a space of repair, of communal gathering and sharing.

'For us, theatre is a space of repair, of communal gathering and sharing'

What advice would you give to upcoming theatre-makers?

Alan: Process wise, what works for us may not work for others. But I think one thing that is generally helpful is to do with care. Looking after yourself and those you’re working with is imperative.

Sophie: Finding people you can be inspired by, that’s precious. If you find someone you can work with, really hold onto that. Keep finding new people to work with. We met at university, but it’s important to keep developing. I think we found a way to challenge, push and help each other.

Jemima: There are plenty of collaborative fish in the sea. I had to hustle – find people and say to them 'I find what you’re doing interesting and I want to be around this interesting thing'. With this project I’m really looking forward to reflecting on mentorship and how we have used this award to connect with practitioners who we’re inspired by like Karen Christopher, Jonathan Burrows, Sarah Wilson-White and Jane Greenfield.

Sophie: You have to go into the lion’s den – like when you go and talk to the person that inspires you. Ask to meet because you’re truly interested. Then perhaps the chemistry will build and you could collaborate in the future. Exercise that interest and learn from them.

Jemima: Prepare and ask good questions. If you can afford it, buy them a coffee.

Sophie: They will respect you for having good questions.

Alan: Get used to rejection but don’t give up too easily. Don’t abuse anyone, don’t be too ugly or too pretty or too short or too tall. Don’t be too talented or completely useless . Always be on time but don’t be too early because that shows you’re too eager! Right level of dis-passion but the right level of concentration . Wear clothes that reveal just enough of your passion. Tattoos – non, non, non!

Mal: Don’t smell!

If your show had to defined by a colour, what would it be?

Mal: Pearlescent. It’s multi-coloured, depending on how you’re looking at it, it changes appearance. But mostly blue, and white and purple.

Jemima: Purple smoke with grey

Sophie: Pearlescent with an edge of fiery orange

Alan: It's a secret, a new colour...

Jemima: I like that, 'the show is a new colour '.

Sophie: That's very arrogant!

(laughs)

The Oxford Samuel Beckett Theatre Trust Award

Alan Fielden with JAMS: Marathon

20–29 Sep 2018

This is theatre for a generation engulfed by the fog of information in the digital age, where the storytelling is disrupted, never fully taking shape, as our narrators try to recall an event.

Book tickets

On Spotify

Listen to the songs that have inspired Marathon:

Production images by Helen Murray and rehearsal images by JAMS.