Introducing:

Isamu Noguchi

Assistant Curator at The Noguchi Museum in New York, Kate Wiener introduces the life and work of Japanese American sculptor, Isamu Noguchi, drawing from Noguchi’s autobiographical writings and documents from The Noguchi Museum Archives.

Delve deeper into the rich history of Noguchi with more recommended reading from The Noguchi Museum Archives throughout the essay.

‘After each bout with the world, I find myself returning chastened and contented enough to seek, within the limits of a single sculpture, the world.’

Over the course of his six-decade career, the Japanese American artist Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) used sculpture as his chosen medium for exploring the world. Working with a vast range of materials and across different cultural and artistic contexts, Noguchi continually expanded sculpture’s reach to encompass the total environment of our awareness. The diversity of his work, along with his refusal to affiliate with any style, movement, or neat categorisation, has made Noguchi a difficult artist to pin down historically. It is also one of his most profound contributions to artmaking and to human understanding. Noguchi modeled an artistic practice and life premised on a sense of openness, exploration, and play that transcended classification.

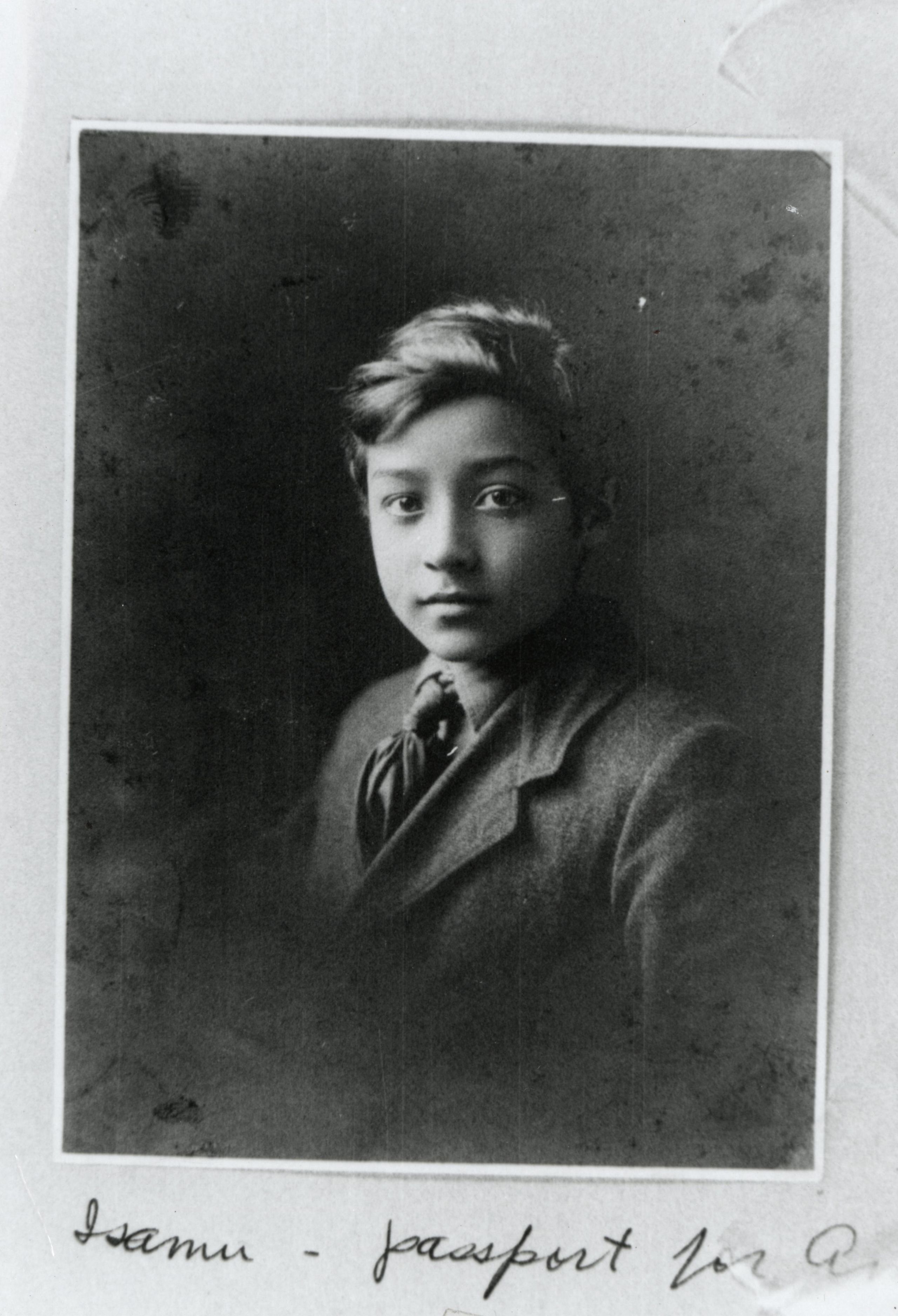

Passport photo of a young Noguchi, 1917–18. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 06035 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst

Passport photo of a young Noguchi, 1917–18. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 06035 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst

For Noguchi, the value of a sculpture was not determined by the traditionally insular concerns of Western art history, aesthetics, or the art market, but rather sculpture’s use in everyday life. Whether they were carved stones, stage sets, paper lanterns, gardens, or playground equipment, Noguchi’s sculptures were designed to be tools for exploring our place in the cosmos, and our relationships to history, nature, and each other. As Noguchi explained, ‘Art for me is something which teaches human beings how to become more human’1.

1904–1928:

Beginnings

‘With my double nationality and double upbringing, where was my home? Where my affections? Where my identity? Japan or America, either, both–or the world?’

Noguchi’s sense of self and home was complex and ever-evolving. He was a biracial American, the son of Léonie Gilmour, a white American writer and editor of mostly Irish descent, and Yonejiro Noguchi, an itinerant Japanese poet. Born in Los Angeles, California, on 17 November 1904, he moved to Japan with his mother when he was just two years old. It was only then that his mostly estranged father, who had returned to Japan before his birth, gave Isamu his official name. Noguchi lived in Tokyo and later Chigasaki with his mother and younger half-sister Ailes Gilmour until the age of thirteen. He later recalled feeling a deep sense of loneliness during his early time in Japan, but also carried an appreciation for certain aspects of his upbringing there, including his memories gardening, watching Obon dances and Kabuki troupes, reading with his mother, and helping to construct his ‘semi-Japanese’ house overlooking Mount Fuji.

In 1918, Léonie arranged for Noguchi to move back to the United States by himself, to attend an experimental school in Indiana that she had read about in a magazine. The school closed shortly after Noguchi’s arrival, but he remained in Indiana where he attended public school, lived with a local family, and developed an appreciation for the vast landscapes of the American Midwest. Noguchi later suspected that Léonie sent him to the United States to shield him from the racism often directed towards mixed-raced individuals in Japan and the painful experience of being ‘half in and half out.2’ She thought it better for him to ‘become completely American.3’ Of course, ‘being completely American’ was not so simple, and experiences of discrimination, difference, and in-betweenness followed Noguchi in the United States. Reflecting on his career at the age of 82 in hisKyoto Prize Commemorative Lecture, Noguchi explained that his desire to create sculpture ‘that is actually very useful, and very much a part of people’s lives’ was deeply informed by his ‘own background: the need for belonging...the need to feel that there is someplace on the earth which an artist can affect in such a way that the art in that place makes for a better life and a better possibility of survival4.’

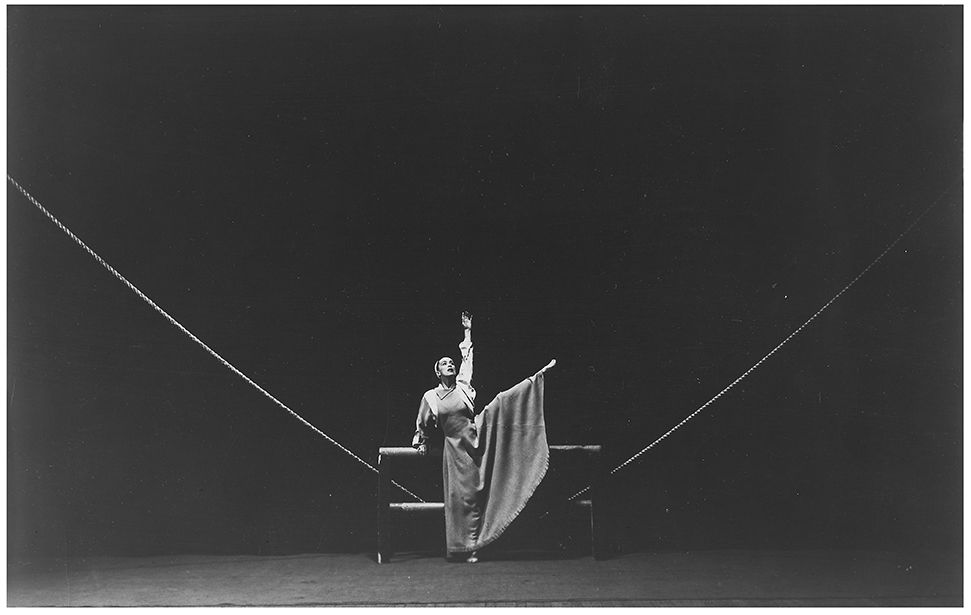

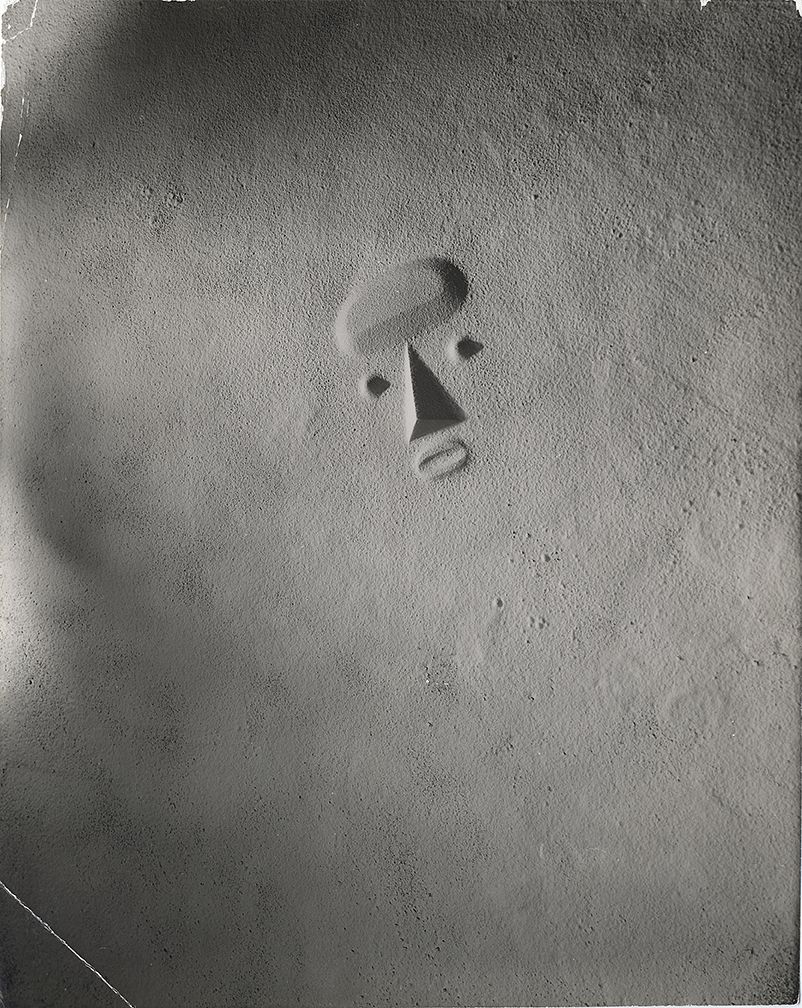

Following high school, Noguchi moved to New York–a city that would remain his on-again, off-again home for the rest of his life. He briefly attended Columbia University as a pre-medical student before dropping out to become an artist. While taking courses at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School on New York’s Lower East Side, where he was taken under the wing of director Onorio Ruotolo, he learned to sculpt in a traditional academic style and was quickly recognised for his virtuosic skill. At the same time, Noguchi was introduced to modern art in the galleries of Alfred Stieglitz and J.B Neumann, who became the young artist’s friends and supporters. Noguchi recalled seeing a 1926 exhibition by the Romanian artist Constantin Brancusi and being ‘transfixed by his vision.5’ He had the rare opportunity to work for Brancusi in Paris the next year, after receiving a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship to fund his artistic development abroad. In his Fellowship application, Noguchi wrote of his aspiration to ‘view nature through nature’s eyes’ and to open up an ‘unlimited field for abstract sculptural expression.6’ In Brancusi’s studio, Noguchi gained a seminal introduction to the modernist principles of abstraction and a deep respect for the handling of materials and tools. Despite Brancusi’s encouragement to produce increasingly ‘uninhibited and true abstractions,7’ free from any fixed reference point, Noguchi recalled feeling too inexperienced and financially insecure to pursue this goal, and instead found himself searching for a way to sustain himself with a different sculptural aim.

’Noguchi wrote of his aspiration to ‘view nature through nature’s eyes’ and to open up an ‘unlimited field for abstract sculptural expression.’’

1929–1940:

Deepening Knowledge

‘I wanted other means of communication - to find a way of sculpture that was humanly meaningful without being realistic, at once abstract and socially relevant.’

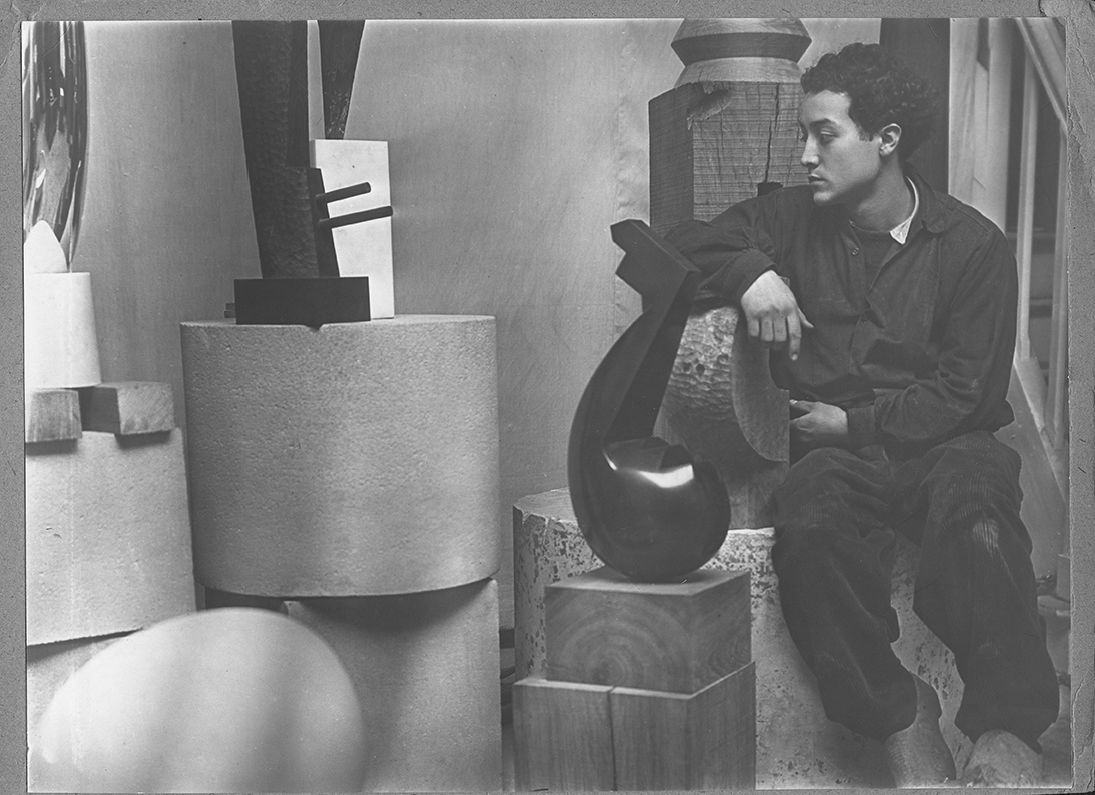

Upon returning to New York in 1929, Noguchi began sculpting portrait busts for patrons and friends as a way to support himself. ‘Headbusting,’ as he disparagingly called it in a 1973 interview with Paul Cummings, was a ‘useful’ way to ‘make money and meet people8.’ This work placed him in contact with several future collaborators and friends, including pioneering choreographer Martha Graham and architect-theorist R. Buckminster Fuller. In 1935, Noguchi created his first of many sets for Martha Graham, for her solo-performance, Frontier. He remembered this set, which consisted simply of two ropes running from the top corners of the proscenium to the ends of a central fence, as a decisive ‘point of departure,’ cultivating his understanding of space as ‘a volume to be dealt with sculpturally9.’

Isamu Noguchi, Stage set with wood element and rope for Martha Graham, Frontier, 1935. Photograph by Barbara Morgan. Noguchi Museum Archives (01508) © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst / Barbara and Willard Morgan photographs and papers, Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

Isamu Noguchi, Stage set with wood element and rope for Martha Graham, Frontier, 1935. Photograph by Barbara Morgan. Noguchi Museum Archives (01508) © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst / Barbara and Willard Morgan photographs and papers, Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA

The start of his long friendship with Fuller, whom Noguchi described as an American ‘messiah of ideas10,’ in the article ‘The Dymaxion American‘ in Time in 1974, marked another turning point in his thinking. In Fuller, Noguchi found a fellow optimist whose humanist vision of a future shaped by technology and innovative design deeply influenced his own evolution as a cross-disciplinary artist, engineer, and designer. Noguchi’s ‘headbusting’ also funded his continued international travels: in 1930 the artist lived in Peking for eight months, where he studied traditional ink-brush painting with the master Qi Baishi, before traveling the next year to Japan where he developed an interest in ceramic traditions and produced a series of terra-cotta sculptures.

Isamu Noguchi, R. Buckminster Fuller, 1929. Bronze, chrome plate, 33.7 x 20 x 25.4 cm. Photograph by F.S. Lincoln. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 01411 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS / Penn State University Libraries

Isamu Noguchi, R. Buckminster Fuller, 1929. Bronze, chrome plate, 33.7 x 20 x 25.4 cm. Photograph by F.S. Lincoln. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 01411 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS / Penn State University Libraries

In a continued effort to locate sculpture’s broader purpose, Noguchi experimented in industrial design and public sculpture (although he had little use for, or interest in, these labels). His designs for a clock, Measured Time (1932), and the shell of Zenith’s Radio Nurse (1937), the first-ever baby monitor, were both put into production, while other ideas like Musical Weathervane (1933), a sculpture designed to make music from the wind and illuminate the skyline, remained in the realm of his ever-active imagination.

Isamu Noguchi, Manufactured by Zenith Radio Corp. Radio Nurse and Guardian Ear, 1937. Bakelite. Radio Nurse: 21 x 17.1 x 15.9 cm. Guardian Ear: 15.9 x 10.8 x 21 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS

Isamu Noguchi, Manufactured by Zenith Radio Corp. Radio Nurse and Guardian Ear, 1937. Bakelite. Radio Nurse: 21 x 17.1 x 15.9 cm. Guardian Ear: 15.9 x 10.8 x 21 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS

In 1935, Noguchi presented several ambitious proposals for public sculptures in a solo exhibition at Marie Harriman Gallery in New York. One of these works was Play Mountain (1935), his radically innovative proposal to transform a full city block into a mountain of sloping and stepped surfaces for sliding, sledding, exploration, and open-ended play. The project was flatly denied by New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. In the exhibition’s catalogue, Noguchi wrote: ‘Sculpture can be a vital force in our every day life if projected into communal usefulness11’. That same year, frustrated by bigoted reviews of his work and an inability to get funding from the Works Progress Administration, Noguchi traveled to Mexico where he was delighted to find that ‘artists were useful people, a part of the community12.’ There, in conjunction with a larger project led by Diego Rivera, Noguchi created History Mexico (1936), a sculpted anti-fascist mural spanning three walls of the Abelardo L. Rodríguez Market in the historic center of Mexico City. Three years later, Noguchi won a competition for his first major public work in the United States: News (1938–1940), a sculptural frieze for the Associated Press Building at Rockefeller Plaza, New York.

’Sculpture can be a vital force in our every day life if projected into communal usefulness’

1941–1948:

Becoming

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity (Triple), 1945 (fabricated 1988) Bronze plate, 141.6 x 56.5 x 49.5 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 9891 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum/ ARS – DACS

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity (Triple), 1945 (fabricated 1988) Bronze plate, 141.6 x 56.5 x 49.5 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 9891 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum/ ARS – DACS

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity (Triple), 1945 (fabricated 1988) Bronze plate, 141.6 x 56.5 x 49.5 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 9891 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS

Isamu Noguchi, Trinity (Triple), 1945 (fabricated 1988) Bronze plate, 141.6 x 56.5 x 49.5 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 9891 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS

‘To be hybrid anticipates the future’

Noguchi’s sense of self, the world, and the role of the sculptor was profoundly altered during World War II. Amidst a growing tide of anti-Japanese discrimination in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Noguchi traveled to Washington to advocate on behalf of Japanese Americans, a community with which he felt a new and urgent bond14. As a New Yorker, Noguchi was exempt from Executive Order 9066, which authorised the War Department to designate and remove individuals from exclusion zones and was used to carry out the forced evacuation of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. Nevertheless, he made the astounding decision to voluntarily enter a prison camp in Poston, Arizona. In a letter to painter George Biddle in 1942, Noguchi wrote that he believed he could ‘help preserve self-respect and belief in America15,’ and attempted to establish an arts and crafts program that could be replicated in other camps. He also planned to rebuild Poston with trees, gardens, and centers for art, recreation, and play.

Within months, Noguchi was overcome with a profound sense of disillusionment as he confronted the brutality of incarceration and suspicion from both internees and camp officials, whom he realised had no intention of supporting his plans. Noguchi attempted to leave Poston, but to his horror, his request was denied. It would be another three months before he was granted a temporary furlough. Noguchi was indelibly marked by this experience, which forced him to reckon with his position in the country and world, and his ability to meaningfully effect change as a sculptor.

Nevertheless, writing about his experience in an unpublished essay titled ‘I Become a Nisei,’ Noguchi expressed his continued faith in an America grounded in multiplicity: ‘To be hybrid,’ he wrote, ‘anticipates the future. This is America, the nation of all nationalities16.’

After his release, Noguchi moved back to New York and established a studio at 33 MacDougal Alley, resolving to ‘be an artist only17.’ But for Noguchi, this did not mean turning his back on the world. Instead, he set out to find new ways to make sense of the human experience in all its complexity and to simultaneously shape the world he desired.

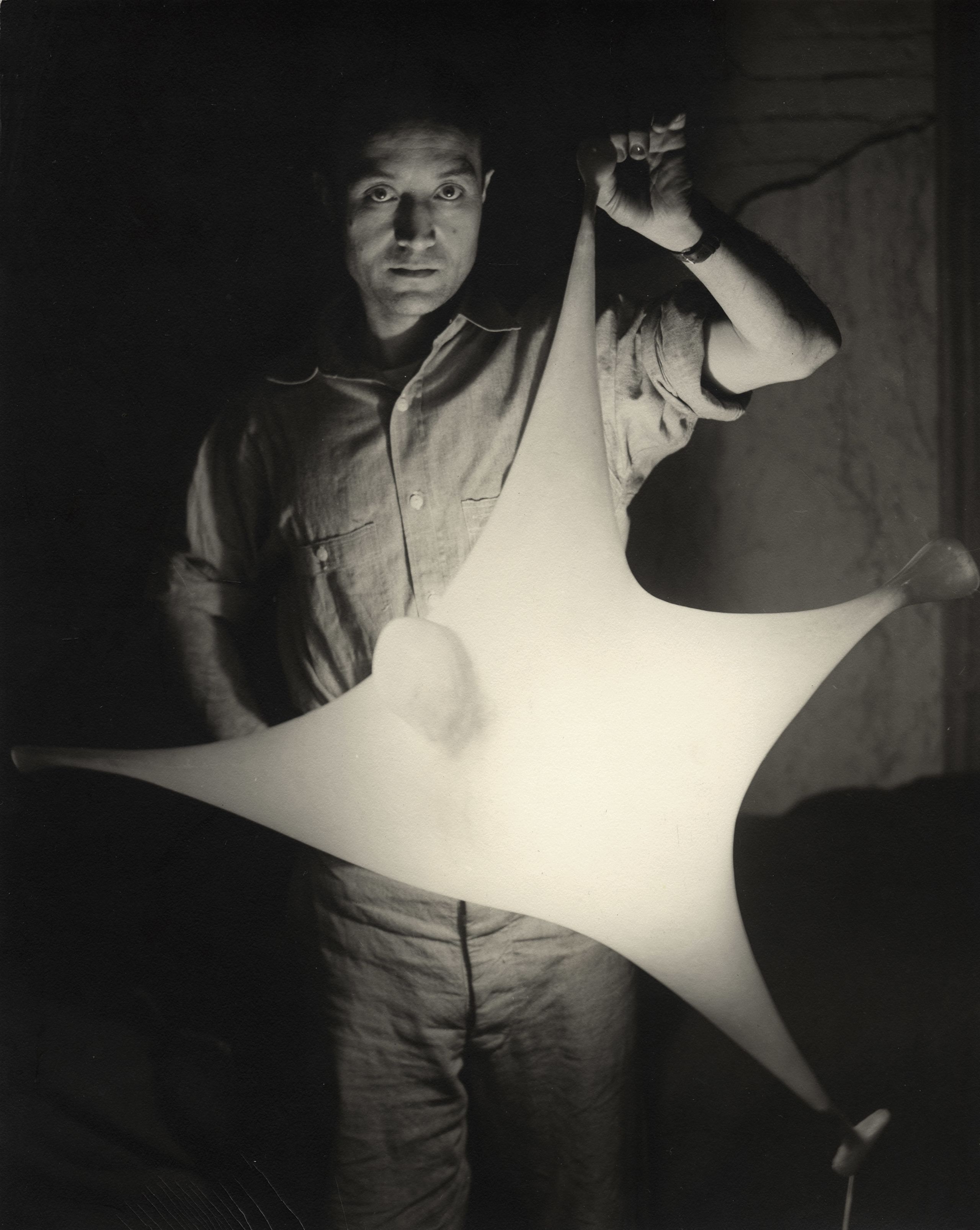

Isamu Noguchi with study for Luminous Plastic Sculpture, 1943. Photograph by Eliot Elisofon. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03766 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum/ ARS – DACS / Eliot Elisofon

Isamu Noguchi with study for Luminous Plastic Sculpture, 1943. Photograph by Eliot Elisofon. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03766 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum/ ARS – DACS / Eliot Elisofon

He devised provocative dance sets and proposals for memorials, and continued to experiment with different materials and forms, including magnesite light sculptures called Lunars, and interlocking marble slab sculptures. He also began working with manufacturers including Lightolier, Knoll, and Herman Miller to produce lights and furniture, including his now iconic Coffee Table (1944).

Isamu Noguchi, Coffee Table, 1944. Manufactured by Herman Miller, 1947–73, 1984–present. Wood and plate glass 40 × 127 × 91 cm Noguchi Museum Archive 10179 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst

Isamu Noguchi, Coffee Table, 1944. Manufactured by Herman Miller, 1947–73, 1984–present. Wood and plate glass 40 × 127 × 91 cm Noguchi Museum Archive 10179 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst

At this time, Noguchi was gaining increased recognition, participating in numerous exhibitions in New York, including the 1946 group show ‘Fourteen Americans’ at The Museum of Modern Art. Many of his works from this period reflected a new sense of precarity. Perhaps most haunting is This Tortured Earth (1942–1943), his unrealised proposal for an earthwork ‘sculpted’ with bombs - the slashed and wounded earth left exposed to ‘memorialize the tragedy of war18.’

Isamu Noguchi, This Tortured Earth, 1942–43 (cast 1977) Bronze. 73.7 × 71.4 × 7.6 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. Noguchi Museum Archives (9860) © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst

Isamu Noguchi, This Tortured Earth, 1942–43 (cast 1977) Bronze. 73.7 × 71.4 × 7.6 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. Noguchi Museum Archives (9860) © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst

‘To be hybrid anticipates the future. This is America, the nation of all nationalities.’

1949–1957:

Seeking

‘I find myself a wanderer in a world rapidly growing smaller. Artist, American citizen, world citizen, belonging anywhere but nowhere.’

Despite his growing success in the New York art world at the end of the 1940s, Noguchi still sought ‘some larger, more noble, and more essentially sculptural purpose to sculpture19.’ In 1949, Noguchi applied for a fellowship from the Bollingen Foundation to travel the world and write a book on ‘the environment of leisure, its meaning, its use, and its relationship to society20’ (Read: A Proposed Study of The Environment of Leisure). By this, he meant civic, social, and religious spaces used across time and cultures for gathering, ceremony, and entertainment. Over the next six years, Noguchi traveled Europe and Asia searching for different ‘use[s] of sculpture in a spatial, cosmic sense,’ from the caves of Lascaux in France and the Angkor Wat temple complex in Cambodia, to the shores of Bali, where he observed shadow-puppet theater and masked performances21. Although Noguchi never actually wrote the proposed book, his journeys around the world profoundly impacted his life and work. He would later say, ‘Our heritage is now the world. Art for the first time may be said to have a world consciousness22.’

During his travels, Noguchi also spent a great deal of time in Japan, returning in 1950 for the first time in nearly two decades. While there, he developed a number of public proposals for the devastated city of Hiroshima and established a new home in Japan in a 200-year-old farmhouse which belonged to the renowned Japanese potter Kitaoji Rosanjin. He lived there with his wife, Yoshiko ‘Shirley’ Yamaguchi, a Japanese movie actress, whom he met in 1950. The two quickly fell in love and were married one year later, but would ultimately divorce in 1957 after a period of separation. Noguchi became particularly invested in Japanese craft traditions at this time: he created his own large body of stoneware sculptures, many inspired by Haniwa, ancient Japanese burial objects, and first developed his now-renowned Akari light sculptures, his modern take on traditional chochin paper lanterns. Noguchi considered Akari to be ‘a true development in an old tradition,’ and over the course of his life developed over 200 different models of these electrically illuminated light sculptures23. (Read: Noguchi, Some thoughts on making of Akari)

Isamu Noguchi, Akari 25N, 1968 117 x 83 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03066 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

Isamu Noguchi, Akari 25N, 1968 117 x 83 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 03066 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

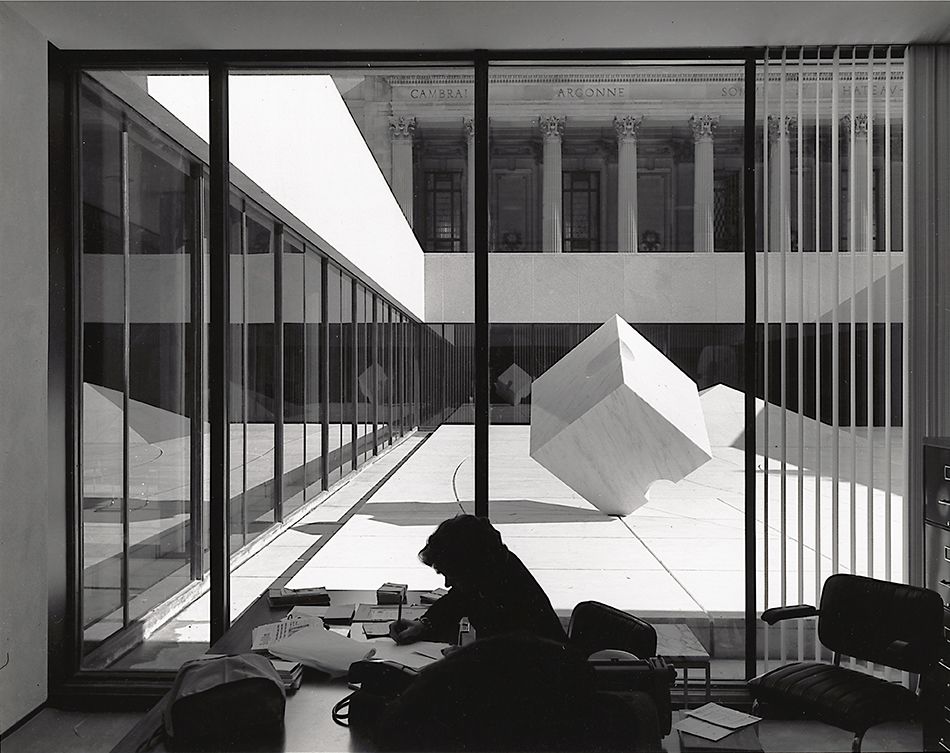

For Noguchi, reinventing tradition was a way of both honoring and transcending a specific history, relating instead to something universal and shared. This vision and his growing identification as a ‘world citizen’ influenced his 1955 design for the United Nations’ UNESCO campus in Paris consisting of a ‘delegate’s patio’ and a ‘somewhat Japanese garden.’ Noguchi wrote: ‘Learning from such a wise tradition, we may seek the rebirth of a major art form; a sculpture garden that shall be of today, personal, timely, yet reaching beyond time24.’

‘Learning from such a wise tradition, we may seek the rebirth of a major art form; a sculpture garden that shall be of today, personal, timely, yet reaching beyond time‘

1958–1979:

Ways of Discovery

‘I could never believe that the experience of sculpture had to be restricted to vision only. The making and ownership of art could also be beyond personal possession–a common and free experience.’

In 1958, after completing the UNESCO project, Noguchi returned to New York and a few years later established a studio in an old factory in Long Island City, Queens. Once there, he quickly became involved in a series of large-scale public projects and more serious collaborations with architects. Some of his most ambitious proposals remained unrealised: among them, his four-block playground for New York’s Riverside Park (1961–1965) designed with the architect Louis Kahn that included innovative play elements like a slide mountain; and his technology-focused lunar garden for the US Pavilion at the Expo ‘70 in Osaka, Japan, which he had hoped to design with NASA’s involvement. Throughout the 60s and 70s, despite continually pushing the limits of feasibility, Noguchi was able to successfully complete more than twenty public works around the world, including gardens, fountains, playgrounds, and plazas. These works boldly reconceived the space of civic and social life and its intersections with nature, time, and transcendence. They also involved close collaboration and often a great deal of sparring with architects, whose demands Noguchi was always creatively working with and against. Although sometimes difficult, his decade-long work with the architect Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), spurred some of his most inspired spaces including sunken stone gardens at the Beinecke Rare Book Room and Library at Yale University, New Haven (1960–1964) and Chase Manhattan Plaza, New York (1961–1964). In 1971, to manage his numerous public commissions, Noguchi established the Noguchi Fountain and Plaza, Inc. with the architect-engineer Shoji Sadao, an invaluable collaborator who helped realise some of Noguchi’s most technologically ambitious projects (as well as those of their mutual friend Buckminster Fuller). Among these projects, was ‘the total environment of leisure25‘ that he designed for Philip A. Hart Plaza in Detroit, Michigan (1971–1979), an eight-acre public space overlooking the Detroit River that includes a sunken amphitheater, stepped seating, and a central fountain. Noguchi described the plaza, which remains a much-used civic center, as a ‘horizon for people26.’

Isamu Noguchi in his 10th Street, Long Island City, Queens Studio, 1964. Photograph by Dan Budnik. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 07281 ©2021 The Estate of Dan Budnik. All Rights Reserved / Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

Isamu Noguchi in his 10th Street, Long Island City, Queens Studio, 1964. Photograph by Dan Budnik. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 07281 ©2021 The Estate of Dan Budnik. All Rights Reserved / Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

During this period, Noguchi also continued his tireless exploration of different materials, experimenting with folded sheet-metal, balsa wood, and bronze. Stone, in particular, became a primary medium for Noguchi, for whom it was expressive of both the past and the future: ‘a congealment of time.’ He said to The New Yorker critic, Calvin Tomkins in 1980, ‘I like to think, when you get to the furthest point of technology, when you get to outer space, what do you find to bring back? Rocks!27’ In order to create his monumental granite sculpture Black Sun (1969), a public commission for the city of Seattle, WA, Noguchi sought the help of the Japanese stone-carver Masatoshi Izumi, who had a studio in Mure on the Japanese island of Shikoku and would become an important collaborator. Noguchi returned to Mure often, and in the early 1970s established a second home there where he continued to live and work part-time for the rest of his life. In subsequent years, Noguchi would become increasingly invested in carving hard Japanese granite and basalt, a practice he regarded as a dialogue with nature and time.

Isamu Noguchi, Sun at Noon, 1969. French red marble, Spanish Alicante marble, 154.9 x 154.9 x 21 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 00687 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

Isamu Noguchi, Sun at Noon, 1969. French red marble, Spanish Alicante marble, 154.9 x 154.9 x 21 cm. Photograph by Kevin Noble. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 00687 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

‘Stone became a primary medium for Noguchi, for whom it was expressive of both the past and the future: ‘a congealment of time‘‘.

1980–1988:

This Earth, This Passage

‘We are a landscape of all we know’

In his later years, Noguchi was thinking deeply about the full scope of his work and his legacy. Largely discontent with the model of traditional museums and the demands of the market-driven art world, Noguchi decided to establish his own museum in a space adjacent to his studio and home in Long Island City, which he carefully renovated the space and installed with his work. The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum officially opened to the public in 1985. Noguchi conceived of the Museum as a repository of his work and record of his thinking, but also as a living resource: a shared space for visitors to come together, reflect, and learn. If the museum is itself a type of spatialised biography, Noguchi began his story at the end, filling the first gallery with his late basalt sculptures. These works in stone represent Noguchi’s continued efforts to engage directly with the earth and its evolution. ‘Stone,’ he said in John Gruen’s The Artist Speaks series for Art in America, ‘is a direct link to the heart of matter - a molecular link. When I tap it, I get the echo of that which we are - in the solar plexus - the center of gravity of matter. Then, the whole universe has a resonance!28’ Noguchi’s museum remains one of his greatest sculpted environments, and like so much of his work, represents his unique capacity to sidestep conventions to create a space for new ways of being and thinking.

Isamu Noguchi tests Slide Mantra at "Isamu Noguchi: What is Sculpture?", 1986 Venice Biennale. Photograph by Michio Noguchi. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 144398 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

Isamu Noguchi tests Slide Mantra at "Isamu Noguchi: What is Sculpture?", 1986 Venice Biennale. Photograph by Michio Noguchi. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 144398 © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

In 1986, Noguchi presented ‘Isamu Noguchi: What is Sculpture?’ in the U.S. pavilion at the forty-second Venice Biennale. Although memories of his incarceration by the United States government during World War II left Noguchi reluctant to accept this prestigious invitation to represent America, he ultimately chose to go through with the exhibition and make it his own, productively blurring the lines between functional design and sculpture, gravity and levity. The centerpiece of his exhibition was a monumental sculpted slide in white marble called Slide Mantra (1986). The America Noguchi represented was the hybrid future of his imaginings—one driven by open-ended possibility, not bound by limiting classifications.

‘Stone is a direct link to the heart of matter - a molecular link. When I tap it, I get the echo of that which we are - in the solar plexus - the center of gravity of matter. Then, the whole universe has a resonance’

In the spring of 1988, the last year of his life, Noguchi conceived of his final and most ambitious playground design: Moerenuma Park (1988–2000), a 454-acre park located on a reclaimed municipal dump outside of Sapporo, Japan designed to include play sculptures, fields, and fountains, and a revised version of his first-ever play concept - the monumental stepped pyramid he called Play Mountain (1933).

Isamu Noguchi (design) with Shoji Sadao (architect), Play Equipment at Moerenuma Koen, 1988-2004. Sapporo, Japan © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

Isamu Noguchi (design) with Shoji Sadao (architect), Play Equipment at Moerenuma Koen, 1988-2004. Sapporo, Japan © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS - DACS

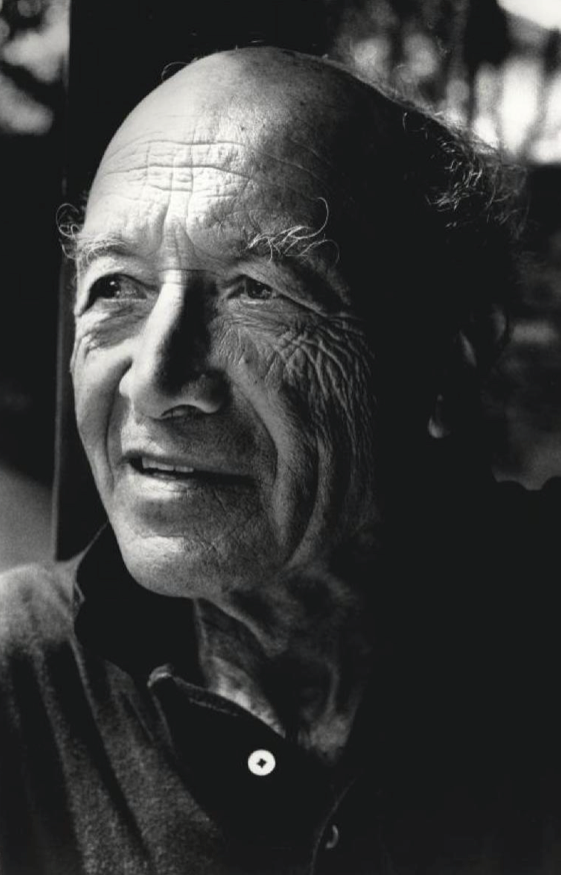

That winter, Noguchi came down with pneumonia and passed away on 30 December 1988 after succumbing to heart failure in a hospital in New York City. Although he did not live to see the completion of Moerenuma Park, this final work encapsulates Noguchi’s lifetime commitment to creating socially meaningful sculpture, and to sculpt the world he wished to inhabit.

Isamu Noguchi photographed by Jun Miki, 1987. Noguchi Museum Archive (04268) © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst

Isamu Noguchi photographed by Jun Miki, 1987. Noguchi Museum Archive (04268) © Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum / ARS – DACS / ProLitteris / VG Bild-Kunst

About the exhibition

Retracing the evolution of Noguchi’s kaleidoscopic career over six decades across sculpture, landscape architecture, dance and design, this exhibition celebrates the artist’s inventive and risk-taking approach to sculpture as a living environment.

Noguchi takes place from Thu 30 Sep 2021–Sun 9 Jan 2022 at Barbican Art Gallery.

About The Noguchi Museum Archive

The Isamu Noguchi Archive contains the most comprehensive body of information on the life and work of Isamu Noguchi. The Archive consists of an extensive photographic collection; manuscripts; correspondence; exhibition, publication, and project records; press clippings; and architectural drawings, as well as documentation of the many objects, artifacts, and tools Noguchi collected during his travels and throughout his lifetime.

Endnotes

[1] Isamu Noguchi and Rhony Alhalel, ’Conversations with Isamu Noguchi,’ Kyoto Journal 10 (Spring 1989): 36. The Noguchi Museum Archives, B_CLI_2067_1989.

[2] Isamu Noguchi, Isamu Noguchi: A Sculptor’s World (Göttingen, Germany: Steidl, 2015), 13.

[3] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 13.

[4] Isamu Noguchi, Kyoto Prize Commemorative Lecture, November 13, 1986, 11–12. The Noguchi Museum Archives, MS_WRI_077_001.

[5] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 16.

[6] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 16.

[7] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 18.

[8] Isamu Noguchi and Paul Cummings, ’Oral history interview with Isamu Noguchi,’ November 7–December 261973. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[9]Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 125.

[10] Noguchi quoted in ’The Dymaxion American,’ Time, January 10, 1964, 49. The Noguchi Museum Archives, MS_COR_244_001.

[11] Isamu Noguchi, exhibition brochure (New York, NY: Marie Harriman Gallery, 1935). The Noguchi Museum Archives, MS_EXH_014_001.

[12] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 23.

[13] Isamu Noguchi, hand-corrected typescript draft of unpublished essay ’I Become a Nisei’ for Reader’s Digest, c. 1942, 1. The Noguchi Museum Archives, MS_WRI_005_001.

[14] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 25.

[15] Isamu Noguchi, Letter to George Biddle, May 30, 1942.

[16] Noguchi, ’I Become a Nisei,’ 1.

[17] Isamu Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 26.

[18] Isamu Noguchi, The Isamu Noguchi Garden Museum (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987), 152.

[19] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 30.

[20] Isamu Noguchi, ’A Proposed Study of The Environment of Leisure,’ c. 1949, 4. The Noguchi Museum Archives, MS_WRI_010_019.

[21] Noguchi and Cummings, ’Oral history interview with Isamu Noguchi.’

[22] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 40.

[23] Isamu Noguchi, ’Some thoughts on the making of Akari,’ c. 1955. The Noguchi Museum Archives, MS_COR_049_008.

[24] Noguchi, A Sculptor’s World, 168.

[25] Isamu Noguchi, The Sculpture of Spaces (New York, NY: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1980), 29. The Noguchi Museum Archives, MS_EXH_181_004.

[26] Noguchi, The Sculpture of Spaces, 29.

[27] Isamu Noguchi quoted in Calvin Tomkins, ’The Art World: Rocks,’ The New Yorker, March 24, 1980: 82. The Noguchi Museum Archives, B_CLI_2003_1980.

[28] Isamu Noguchi quoted in John Gruen, ’The Artist Speaks: Isamu Noguchi,’ Art in America 56 (March-April 1968): 29. The Noguchi Museum Archives, BM_JOU_0292_1968