Introducing:

Lee Krasner

A key figure in American art, Krasner's energetic works reflect the spirit of possibility in post-war New York. Charlotte Flint, Exhibition Assistant on Lee Krasner: Living Colour, looks back through her life, works and legacy.

‘I was a woman, Jewish, a widow, a damn good painter, thank you, and a little too independent…’

Lee Krasner and her younger sister, Ruth, c. 1915–16. Unknown Photographer

Lee Krasner and her younger sister, Ruth, c. 1915–16. Unknown Photographer

Self-Portrait, c. 1928,The Jewish Museum, New York. © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Courtesy the Jewish Museum, New York

Self-Portrait, c. 1928,The Jewish Museum, New York. © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Courtesy the Jewish Museum, New York

Krasner was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1908 almost nine months to the day after her parents were reunited. Joseph, Krasner’s father, had emigrated to the United States from a small village in Russia three years earlier to escape brutal anti-Jewish violence and to seek a new home for his family. The first of the Krasner children to be born in America, Lee joined three sisters and a brother, and a younger sister, Ruth, arrived in 1910. Krasner’s family were Jewish Orthodox and spoke a mixture of Russian, Yiddish and English. She dutifully recited the morning prayer in Hebrew and it was only later in her life that she read the English translation. She recalled how, ‘if you are a male you say, ‘Thank you, O Lord, for creating me in your image.’ If you are a female you say, ‘Thank you, O Lord, for creating me as you see fit’, and that started up a revolution that I have not recovered from’. Krasner began to rail against the treatment of women in Jewish scripture, renouncing religion completely by the time she was a teenager.

‘I was brought up to be independent. I made no economic demands on my parents so in turn they let me be… I was not pressured by them, I was free to study art. It was the best thing that could have happened’.

Krasner grew up against a backdrop of increasing liberation for women in the United States, who were granted the right to vote in August 1920, while popular Yiddish cinema featured rebellious ‘jazz babies’, who renounced the backwardness of their parents and adopted dreams of being American and individual.

When she was just 14, fuelled by this spur towards ambition and independence, Krasner decided to pursue an artistic career. First at Washington Irving High in Manhattan – at the time, the only school in Greater New York to offer an art course for girls – and then at Cooper Union and the National Academy of Design, Krasner learned to draw and paint in the manner of the period. This conventional approach and style was to undergo a dramatic transformation in 1930, when she discovered Modern art. She fell in love with the work of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso after viewing their work at the Museum of Modern Art, which first opened its doors on 8 November 1929, describing the occasion as ‘an upheaval for me… an opening of a door’.

Krasner’s fascination with modernism led her to Hans Hofmann, the German artist and teacher who had known Picasso and Matisse in Paris, and had established his avant-garde school in New York in 1934. Advocating a dramatically different approach to the Academy, Hofmann encouraged Krasner to radically deconstruct the model’s body in her drawings. Krasner immersed herself in Hofmann’s teachings on Cubism and the pair developed a mutual respect for each other’s practice – with Hofmann bestowing on one of Krasner’s paintings the (shockingly backhanded and sexist) praise: ‘This is so good, you would not know it was painted by a woman!’.

‘The Jumble Shop would be one place where we’d sometimes accumulate down in the Village…at one point we might be bellyaching about some imposition the WPA forced upon us.

Another time it might be completely aesthetic discussion; you know, whether we had just seen a new Picasso reproduction or something…’

Living in Greenwich Village in the 1930s placed Krasner at the heart of a flourishing downtown New York art scene, where she was one of only a handful of female artists. Working as a waitress at the Greenwich Village nightclub Sam Johnson’s, an artistic and literary hub, she met important figures including the writer Harold Rosenberg. Although the artistic scene was blossoming, it was sharply juxtaposed against the widespread poverty and stagnant job market caused by the Great Depression, triggered by the 1929 Wall Street Crash. Artists at this time struggled immensely to continue making work in this harsh climate. Franklin D. Roosevelt later made a speech pledging his assistance to the suffering American population, launching the New Deal programme to counter widespread poverty. The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) was born, a scheme that would employ more than 3,700 artists to decorate public buildings.

‘There was no discrimination against women that I was aware of in the WPA. There were a lot of us working then – Alice Trumbull Mason, Suzie Freulingheusen, Gertrude Greene and others. The head of the New York project was a woman, Audrey McMahon’.

The PWAP went through a number of transformations – from the WPA to the War Services Project – and Krasner was an active participant throughout. The government programme promoted strictly non-discriminatory policies and Krasner, who was by now having her work exhibited in important exhibitions, was chosen to oversee large crews of artists working on projects of a significant scale. As with many women artists at this time, the scheme gave her an opportunity to gain a professional reputation, to hone her skills and to work as part of a like-minded community; Krasner recalled: ‘Not everybody, but almost everybody touched it… and I feel it surely helped carry a great many of the painters through a period of time where it would have been extremely difficult for them to survive’.

Lee Krasner, c. 1938. Unknown photographer

Lee Krasner, c. 1938. Unknown photographer

‘I was practically in every jail in New York City.

Each time we were fired, or threatened with being fired, we’d go out and picket. On many occasions we’d be taken off in a Black Maria and locked in a cell’.

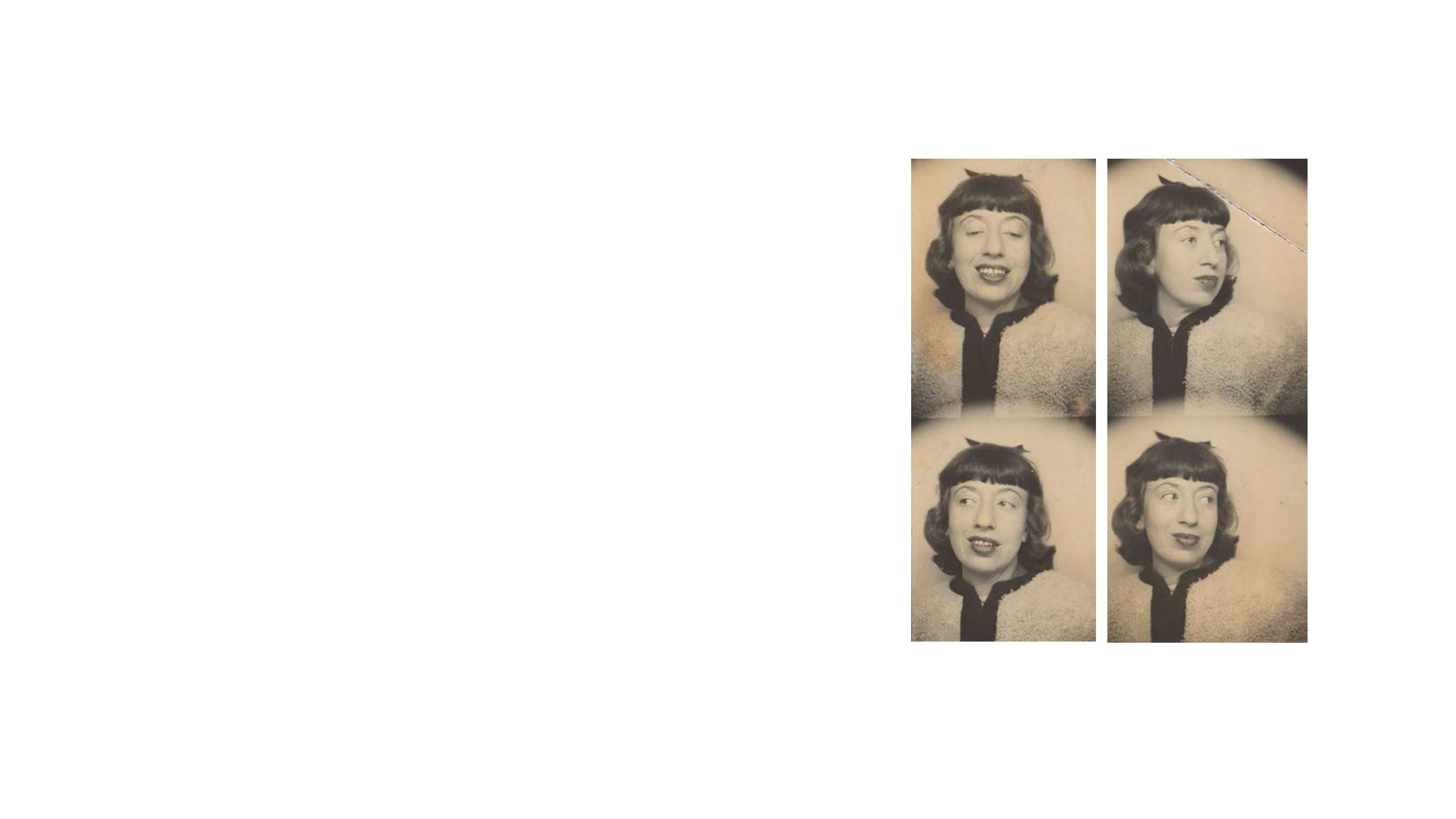

Lee Krasner at the WPA Pier, New York City, where she was working on a WPA commission, c. 1940. Photograph by Fred Prater. Lee Krasner Papers, c.1905-1984. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Lee Krasner at the WPA Pier, New York City, where she was working on a WPA commission, c. 1940. Photograph by Fred Prater. Lee Krasner Papers, c.1905-1984. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Krasner was politically active during the 1930s and 40s attending numerous protests to demand union recognition and wage increases. On 1 December 1936, Krasner joined a large group of artists and artists’ models in a strike to protest the imminent redundancy of 500 WPA workers. Following violent clashes with the police, several protesters were arrested, including Krasner, who booked herself in as the American Impressionist painter Mary Cassat. In prison, Krasner met the artist Mercedes Carles (later Mercedes Matter) with who she would form a close friendship.

‘[The Surrealists] treated their women like French poodles, and it sort of rubbed off on the Abstract Expressionists. The exceptions were Bradley Walker Tomlin, Franz Kline, and Jackson Pollock. That might be the end of my listing. The other big boys just didn’t treat me at all. I wasn’t there for them as an artist’.

While Krasner was gaining recognition and respect within the New York art scene, she continued to rail against the discrimination rife within the male dominated world of artists, writers and critics in the city. Although she faced this with her usual tenacity, Krasner was frequently overshadowed by surrounding male artists – notably by her partner, and later husband, the artist Jackson Pollock. As one of the first generation Abstract Expressionists, Krasner’s fight for recognition as a woman artist helped open up opportunities for future female Abstract painters including Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler.

‘Jackson always treated me as an artist… he always acknowledged, was aware of what I was doing… I was a painter before I knew him, and he knew that, and when we were together, I couldn’t have stayed with him one day if he didn’t treat me as a painter’.

Meeting in New York in 1941 as co-exhibitors in John Graham’s exhibition American and French Paintings (1942), Krasner and Pollock fell quickly in love and they married in October 1945. Following mounting frustrations with the fickleness of the New York City art scene, the pair moved to a clapboard farmhouse on Fireplace Road in Springs, East Hampton. A world away from the densely populated city, the couple were immersed in the peaceful nature of the local area, and Krasner described her new bucolic life as an ‘idyllic experience’.

‘The grayness of the streets finally began to open up in the 'Little Image' paintings, it was a great change’.

It was here that Krasner produced her ‘Little Images’, brilliant jewel-like compositions inspired by her picturesque natural surroundings. Executed on the table or the floor in an upstairs bedroom of the house, Krasner was confined to a small working space, while Pollock occupied a larger studio in a converted former barn. These cramped quarters didn’t stem her productive streak however, and Krasner proceeded to make some of the most important works of her career – the critic Clement Greenberg exclaiming, ’That’s hot, it’s cooking!’, after viewing one for the first time. While the blissful natural environment was stimulating to Krasner’s artistic practice – she had one of her most successful exhibitions to date in 1955, at Eleanor Ward’s Stable Gallery – cracks in her relationship with Pollock were becoming more prominent.

‘Let me say… I was going down deep into something which wasn’t easy or pleasant’.

Untitled, 1946 Collection of Bobbi and Walter Zifkin © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Photograph by Jonathan Urban.

Untitled, 1946 Collection of Bobbi and Walter Zifkin © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Photograph by Jonathan Urban.

‘Painting is not separate from life. It is one. It is like asking - do I want to live? My answer is yes - and I paint’.

In 1956, Pollock began a public affair with the painter Ruth Kligman, and his alcoholism had worsened significantly. Invited by friends to visit them in Europe, Krasner took the opportunity for a break and left Pollock behind in East Hampton. While in France, Krasner received a telephone call from Clement Greenberg to inform her that Pollock had crashed his car and died. At the age of forty-seven, Krasner found herself a widow. Despite the immense period of grief that followed Pollock’s death, Krasner’s artistic output never waned, and the paintings made at this time were described as a ‘stunning affirmation of life’.

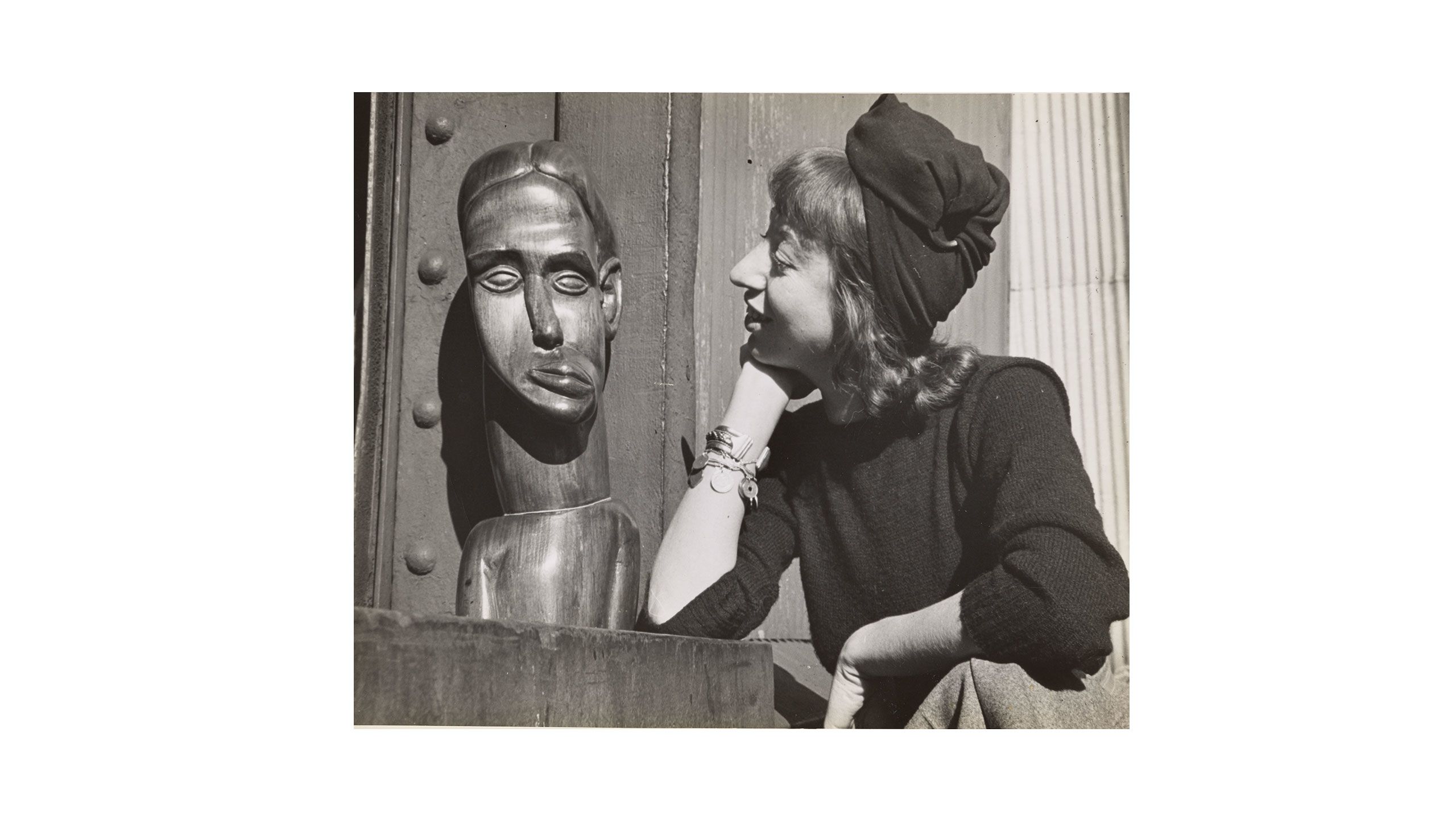

A year after Pollock’s death, Krasner decided to move her studio into the barn in Springs. Although it must have been a space loaded with painful memories, it was also the largest working area on the property which finally allowed her to work on a bigger scale. Ever practical, Krasner explained ‘there was no point letting [the studio in the barn] stand empty’, demonstrating her dedication to her artistic practice, even in the wake of personal tragedy. The paintings swelled in size, with canvases reaching up to 4.4m in length. Following the death of her mother in 1959, Krasner experienced severe insomnia and worked at night under the artificial light of her studio. Due to the lack of natural light, Krasner refused to work with colour and instead used a purposefully limited palette of raw and burnt umber on canvas. The result was a powerful series of paintings that her friend, the poet Richard Howard dubbed her ‘Night Journeys’.

‘Aesthetically I am very much Lee Krasner. I am undergoing emotional, psychological, and artistic changes but I hold Lee Krasner right through’.

Lee Krasner standing on a ladder in front of The Gate (1959) before it was completed, Springs, July or August 1959. Photograph by Halley Erskine.

Lee Krasner standing on a ladder in front of The Gate (1959) before it was completed, Springs, July or August 1959. Photograph by Halley Erskine.

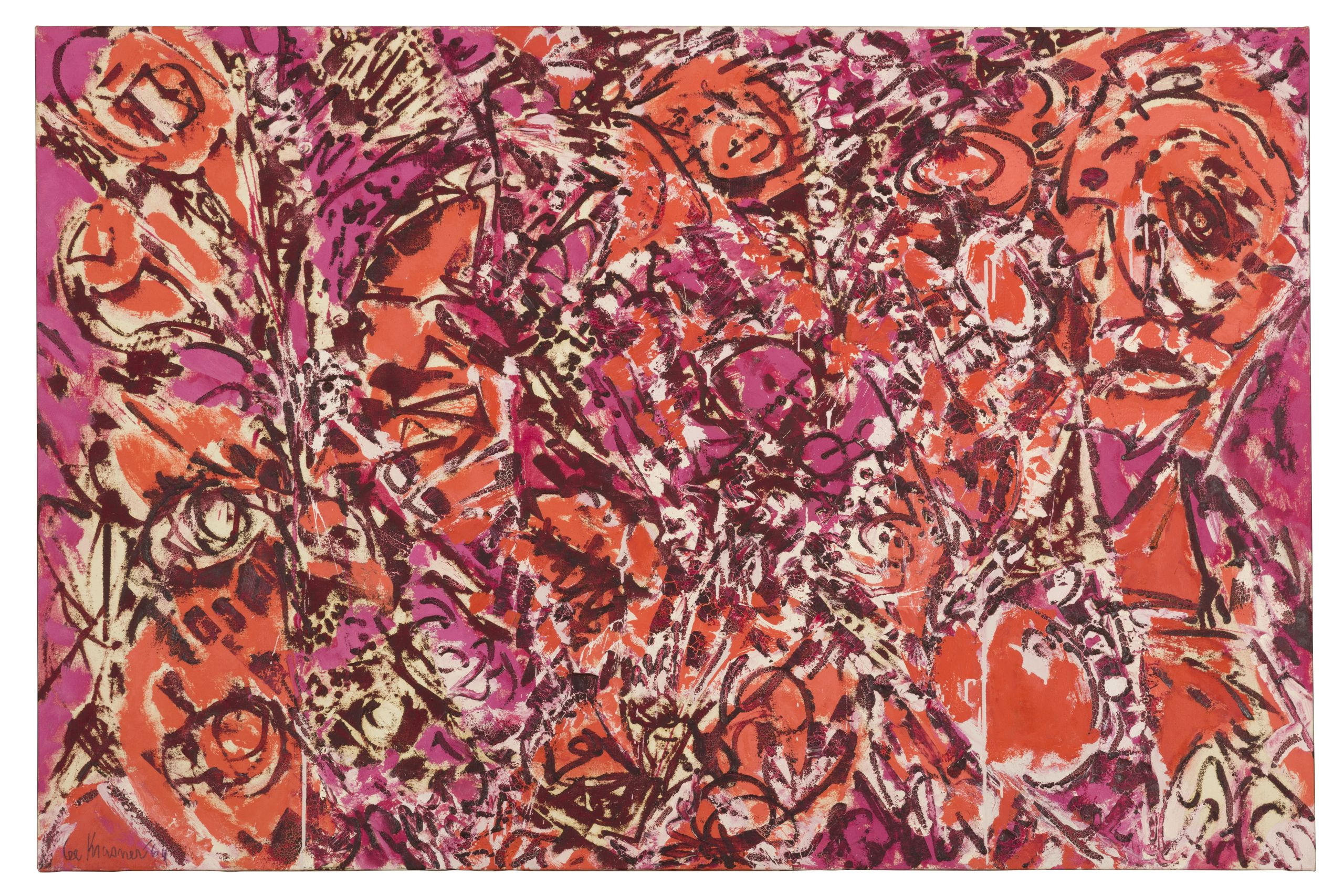

In 1960, after overcoming her insomnia, Krasner allowed colour to burst back into her painting. A riot of dissonant hues emerged – fuschia pink, hot orange, vibrant Kelly green – in what Krasner called her ‘Primary Series’. Continuing to work at a large scale – some of the canvases were almost 5 metres in length – these eye-watering colours confronted the viewer in vast unflinching planes. Of these new paintings, the art critic Robert Hughes said: ‘their blossoming was remarkable. In fact “blossoming” is hardly the word, for it suggests a soft, floral, ethereal event, adjectives one would not pick for the tough paintings, often full of barely controlled anger, that she was to produce after 1960… Is there a less “feminine” woman artist of her generation? Probably not’. Krasner was working with frenetic energy at this point in her career, producing more than 160 paintings and experimental works on paper in 7 years. Krasner was now achieving widespread recognition and respect for her works – including her first survey exhibition organised by Bryan Robertson at the Whitechapel Gallery in London in 1965 – which was met with very positive reviews.

Polar Stampede, 1960 The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Image courtesy Kasmin Gallery.

Polar Stampede, 1960 The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Image courtesy Kasmin Gallery.

‘Painting is a revelation, an act of love… as a painter I can’t experience it any other way’.

Icarus, 1964. Thomson Family Collection, New York City. © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, courtesy Kasmin Gallery, New York. Photo: Diego Flores.

Icarus, 1964. Thomson Family Collection, New York City. © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, courtesy Kasmin Gallery, New York. Photo: Diego Flores.

At the same time as producing these significant paintings, Krasner was managing Pollock’s estate and, as always, promoting his legacy. Unkindly dubbed an ‘art widow’, who had a reputation as a fierce negotiator on the New York art scene, Krasner was regarded with a degree of trepidation. On visiting her in East Hampton in 1964 however, artist Paul Huxley recounted: ‘Lee was not what she had been branded. In New York myth she was the monstrous Gorgon who guarded the Pollock estate. In person, though feisty, she was a warm and generous-spirited woman whose circumstances had forced her to stand up to the male prejudiced elite of critics and dealers hell-bent on devouring her husband’s life work’.

‘I couldn’t run out and do a one-woman job on the sexist aspects of the art world, continue my painting, and stay in the role I was in as Mrs Pollock… What I considered important was that I was able to work and other things would have to take their turn’.

Forthright, independent and strong, Krasner spent her life defending herself, her practice, and the work of her husband Jackson Pollock against an often cruel art world. By the 1970s however, she was finally yielding the respect and recognition she so richly deserved, with the art critic Emily Genauer declaring in 1973: ‘surely she’s painting better now than ever before’. Another key factor in the somewhat belated recognition of her work was the rise of second-wave feminism in the 1970s, about which Krasner quipped: ‘It’s too bad that the women’s liberation didn’t occur thirty years earlier in my life. It would have been of enormous assistance at that time’.

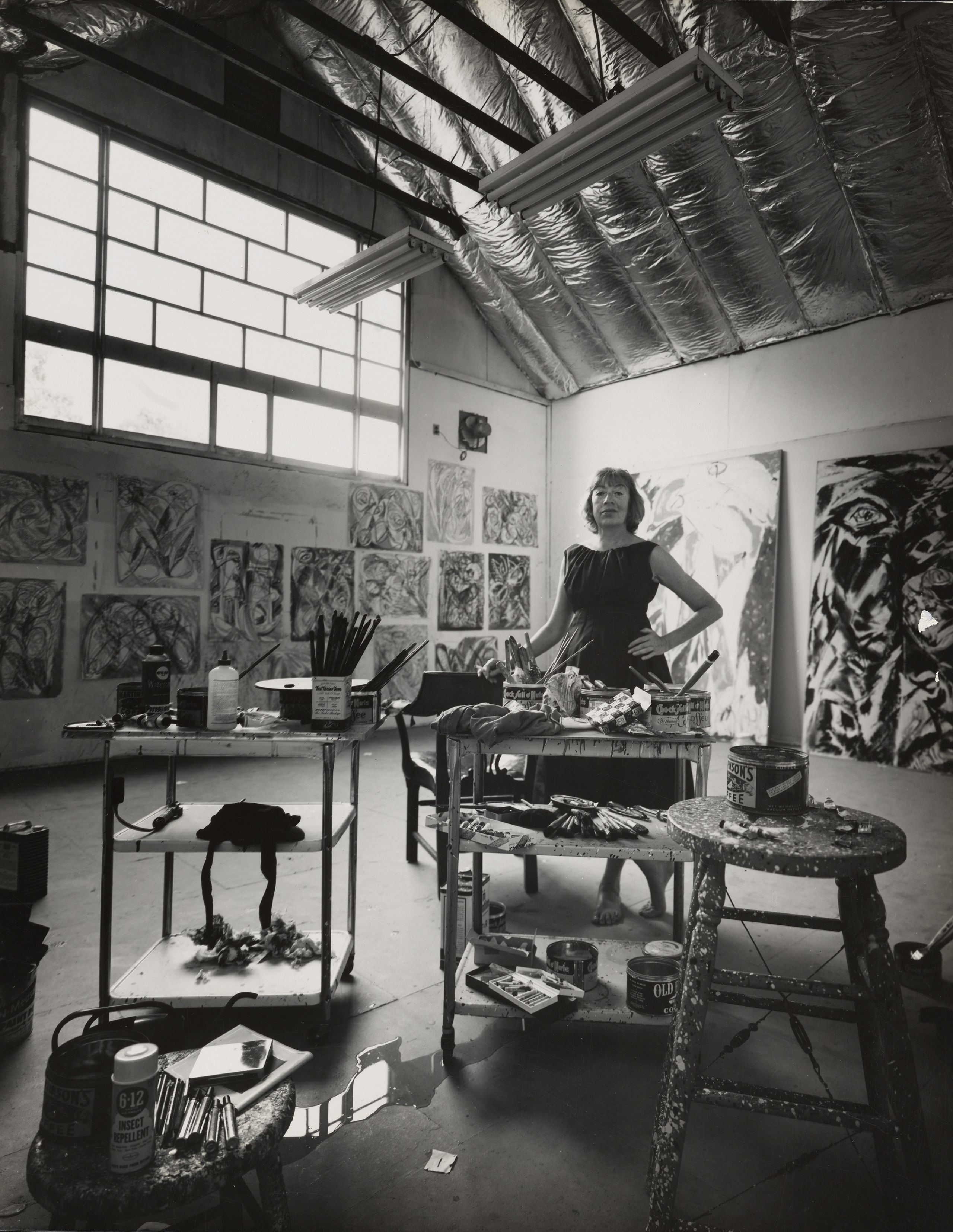

Lee Krasner in her studio in the barn, Springs, 1962 Photograph by Hans Namuth. Lee Krasner Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Lee Krasner in her studio in the barn, Springs, 1962 Photograph by Hans Namuth. Lee Krasner Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

‘I go on the assumption that the artist is a highly sensitive, intellectual and aware human being… It’s a total experience which has to do with the sensitivity of being a painter. The painter’s form of expressing [them]self is through painting’.

r

Palingenesis, 1971. Collection Pollock-Krasner Foundation. © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, courtesy Kasmin Gallery, New York.

Palingenesis, 1971. Collection Pollock-Krasner Foundation. © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation, courtesy Kasmin Gallery, New York.

In 1973, Lee Krasner: Large Paintings opened at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York, a significant milestone in Krasner’s professional career. In the accompanying catalogue, curator Marcia Tucker said: ‘Today, Lee Krasner is considered a prototype by many younger painters. She is encouraging and generous, tough and strong-willed, gregarious and adventurous, full of anecdotes and ideas. Most important, the enthusiasm for her work continues to grow as the contributions she has made are being fully realised’. Krasner’s significance as an inspiration for younger artists and practitioners cannot be understated, and Tucker’s words resonate more clearly now than ever. In our current moment, museums and galleries are seeking to address the lack of diversity within their collections, questioning the canonical view of art history by foregrounding the work of women. Female artists are fetching record prices at auction and 2019 promises exhibitions of women were often marginalised and ignored at the expense of their male counterparts.

In her recent book Ninth Street Women, author Mary Gabriel says of the female Abstract Expressionist painters: ‘these women changed American art and society, tearing up the prevailing social code and replacing it with a doctrine of liberation’ , a statement that is exemplified when read in the context of Krasner’s life. Pursuing a career in art against the ruins of the American Depression and the Second World War and constantly working against the misogyny of the New York art scene, Krasner faced many challenges, yet continued making work against all obstacles. One of the most tenacious artists of the twentieth century, Krasner demonstrates the fundamental role that these avant-garde women played in shaping our current landscape and we are delighted to give her voice the platform it richly deserves.

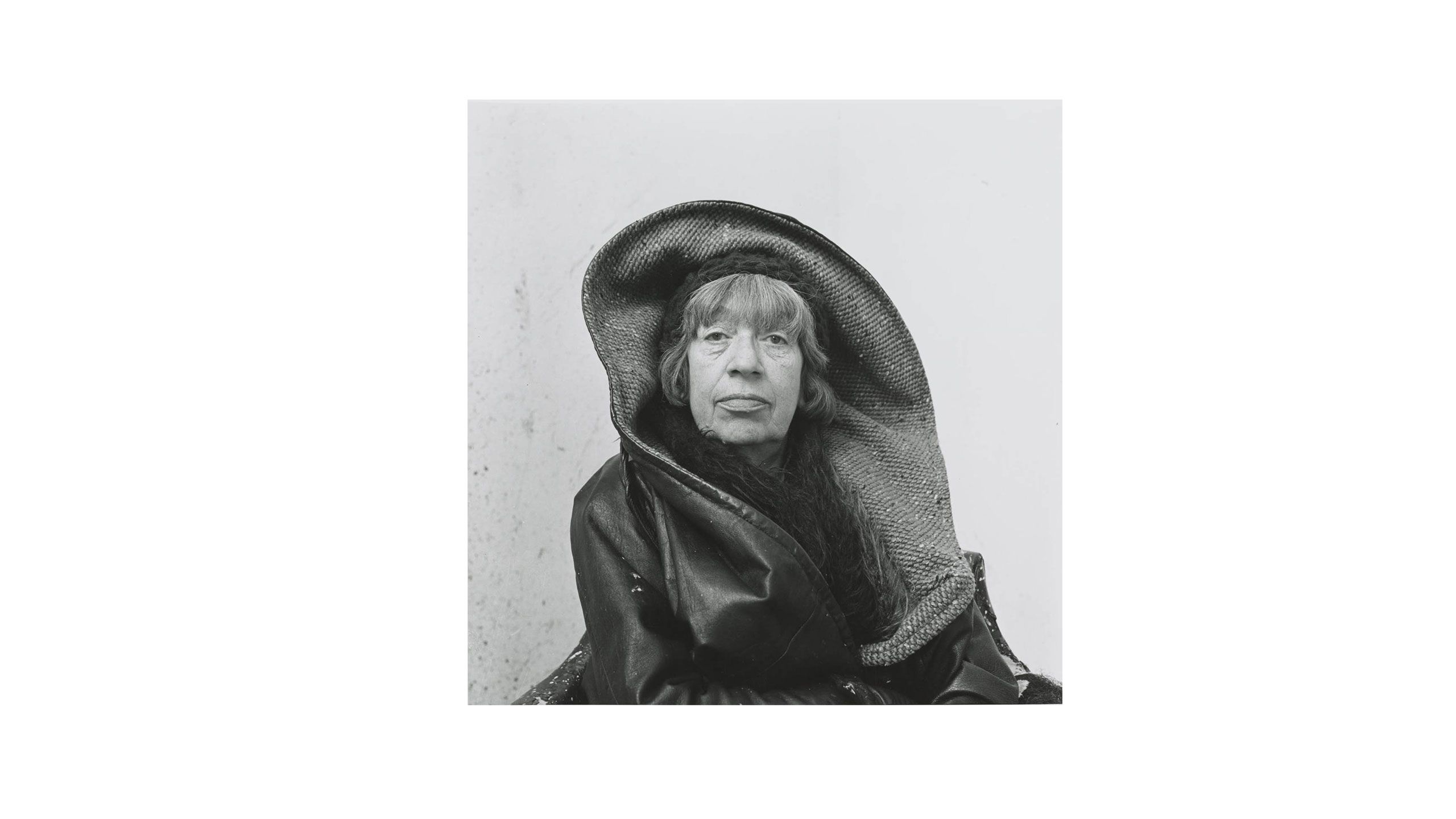

Lee Krasner, Springs, NY, 1972. Photograph by Irving Penn © The Irving Penn Foundation

Lee Krasner, Springs, NY, 1972. Photograph by Irving Penn © The Irving Penn Foundation

About Lee Krasner: Living Colour

Lee Krasner: Living Colour celebrates the work and life of Lee Krasner (1908–1984), a pioneer of Abstract Expressionism. The first major presentation of her work in Europe for more than 50 years, this exhibition tells the story of a formidable artist, whose importance has too often been eclipsed by her marriage to Jackson Pollock.

The exhibition takes place from 30 May–1 September 2019 in the Barbican Art Gallery.

Photo: Lee Krasner in her New York studio, © 1939. Photograph by Maurice Berezov. Copyright A.E. Artworks, LLC