Dorothea Lange:

A Life in Pictures

We look back through the life and work of pioneering documentary photographer and visual activist, Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) to coincide with the first UK retrospective of her work, Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing.

1902

Rising against adversity in her childhood, Lange contracted polio at the age of seven which left her with a permanently disfigured right leg and foot that caused a slight limp, a disability that would profoundly affect her personality

and self-perception.

‘I think it perhaps was the most important thing that happened to me, and formed me, guided me, instructed me, helped me, and humiliated me. All those things at once … Years afterwards when I was working, as I work now, with people who are strangers to me, where I walk into situations where I am very much an outsider, to be a crippled person, or a disabled person, gives an immense advantage. People are kinder to you. It puts you on a different level than if you go into a situation whole and secure.’

Untitled (Dorothea Lange’s Foot), 1957 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Untitled (Dorothea Lange’s Foot), 1957 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

1919

Lange opened a portrait studio advantageously located in San Francisco’s high-end commercial district that quickly attracted the bohemian and bourgeois elite of the Bay Area. The studio became ‘a kind of clubbish place’

where friends, acquaintances and customers gathered after hours. It was also a commercial success: ‘I had the cream of the trade,’ she said later, ‘I was the person to whom you went if you could afford it.’

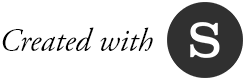

Lange’s portraits from this period – from 1919 until the close of her studio in 1934 – are intimate and informal keepsakes that capture the inner lives and family relations of her sitters, many of whom belonged to

her inner circle, including the photographer Roi Partridge.

Roi Partridge Portrait, San Francisco, c. 1925 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Roi Partridge Portrait, San Francisco, c. 1925 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

1933

By the early 1930s the effects of the Great Depression – caused by the stock market crash of 1929 coupled with severe droughts in the so-called Dust Bowl states – reverberated across America. The streets of San Francisco were brimming with the hungry and unemployed.

This new reality proved a catalyst for Lange, who felt compelled to venture out of the confines of her studio to photograph the urban homeless, and in so doing found her documentary voice. One of her first and most famous photographs shows

hungry men queuing up for food at the White Angel Breadline in San Francisco.

Man beside Wheelbarrow, San Francisco, 1934 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Man beside Wheelbarrow, San Francisco, 1934 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

‘I knew I was looking at something. You know there are moments such as these when time stands still and all you do is hold your breath and hope it will wait for you. And you just hope you will have enough time to get it organized in a fraction of a second on that tiny piece of sensitive film.’

Dorothea Lange

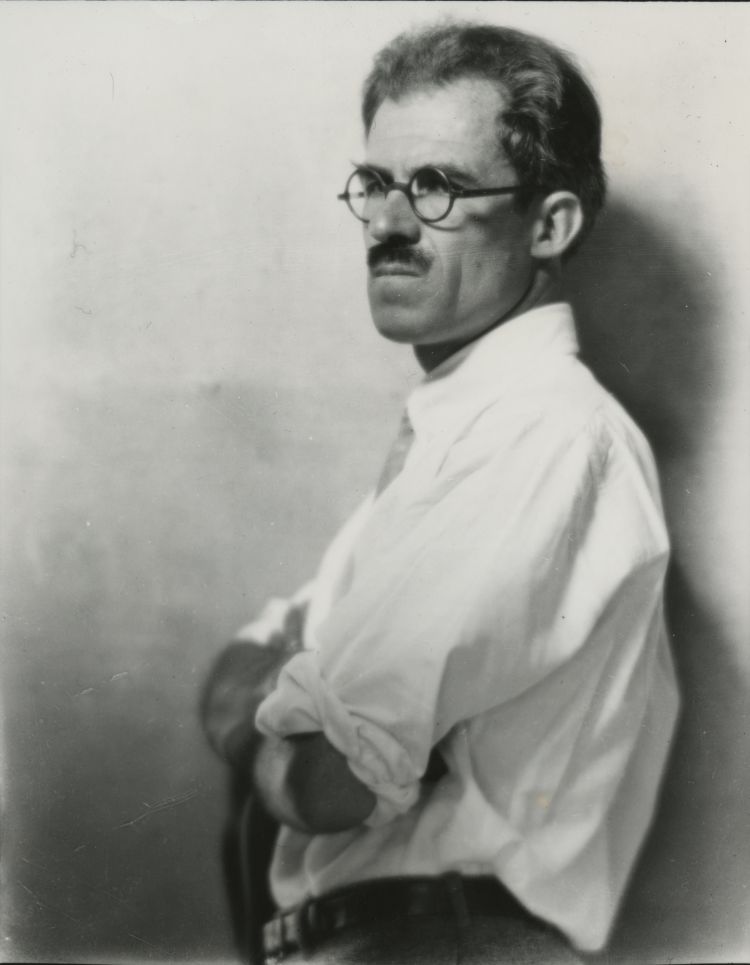

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882–1945) was elected as President of the United States and inaugurated in March 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression. Roosevelt launched the New Deal programme to counter widespread poverty and help those most affected by the Depression, including tenant farmers, migrant workers and victims of drought in the southern plains.

The Resettlement Administration was established as part of the New Deal programme, and Roy E. Stryker – the charismatic chief of the Historical Section of the Information Division – started a pioneering photography project. He hired a team of photographers to create a visual record of America that could be used free of charge by press nationwide. Over the course of half a decade, the division amassed approximately 270,000 photographs.

1935

Lange combined her efforts to photograph the effects of the Great Depression with Paul Schuster Taylor (1895-1984), an esteemed social scientist and expert in farm labour from the University of California who understood the power of photography

to effect change. Together they produced ground-breaking, government-commissioned reports which combined Taylor’s analysis with Lange’s powerful images. As a result of her collaborations with Taylor – who she married

in December 1935 – Lange was employed by the newly formed Resettlement Administration (later renamed Farm Security Administration) in 1935.

Between 1935 and 1940 Lange criss-crossed the United States documenting the plight of migratory farm workers and Dust Bowl refugees as they headed west across the country. The personal and compassionate qualities of Lange’s work,

which make her photographs such moving documents, awakened public awareness and created national sympathy for the thousands of migrants of the Great Depression.

Drought Refugees, c. 1935 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Road West

Drought Refugees, c. 1935 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Road West

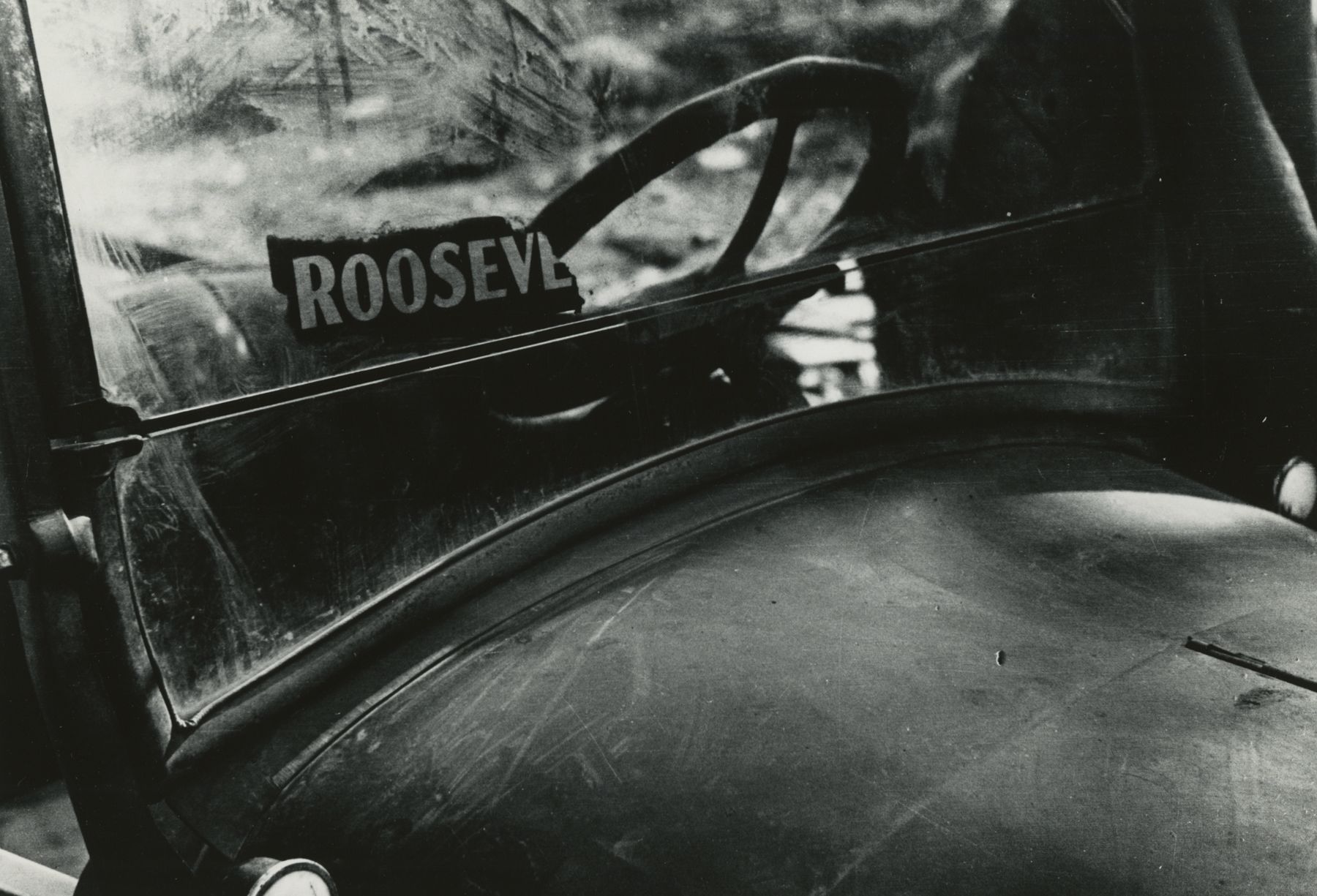

1936

In 1936, Lange was on her way back home from shooting in central California on assignment for the RA (later known as the FSA) when she drove past a signpost to a pea pickers’ camp near the town of Nipomo, where 2,500 pea pickers

were out of work, nearly out of food, and camping in desperation. Lange set up her large-format (4x5”) camera and made seven exposures of Florence Owens Thompson and her children all the while moving in closer to get the frame

she wanted. Lange usually spent time talking with people and making notes, but her interaction with Thompson was brief and it took less than ten minutes to take the iconic photograph known today simply as Migrant Mother.

The final shot in the sequence was immediately picked up by the illustrated press, setting the pattern for the photograph’s countless reproductions as an isolated symbol. It has since become a universal icon of human dignity and

defiance in the face of adversity.

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

1942

Lange was hired by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) to document the internment of Japanese American citizens in 1942, following the Japanese attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Pre-existing anti-Japanese

sentiment spiralled into a full-fledged racial hysteria and President Roosevelt ordered the ‘evacuation’ of all Japanese American citizens on the Pacific Coast.

Between March and July 1942, Lange documented the Japanese American community as they prepared to leave behind their homes, businesses and belongings, before being transferred to internment camps for the duration of the war, where dehumanising

living conditions deprived them of purpose, privacy and comfort.

It was a troubling task that left Lange feeling deeply conflicted and powerless in the face of the government’s disturbing policy. Lange waived the rights to her pictures to the WRA, and a number of photographs were classified

as ‘impounded’. She later said: ‘They [the WRA] had wanted a record, but not a public record.’

Centerville, California, 1942 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Centerville, California, 1942 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

1943-44

In collaboration with Ansel Adams (1902-1984), Lange secured a commission from Fortune magazine to document 24-hours in the lives of shipyard workers in Richmond, which had become one of California’s major shipbuilding

hubs producing large merchant vessels used to supply Allied troops. Lured by the promise of work, the population of the San Francisco Bay Area exploded as men and women flocked to the west in vast numbers, prompting the San Francisco

Chronicle to claim that the region was in the grips of a ‘second gold rush’.

Drawn to images that transgressed accepted attitudes towards gender and race, Lange settled her lens on African American female welders and stylishly dressed women flaunting their newfound independence and spending power. Creating heroic

images of women at work, Lange’s photographs contributed to the archetypal image of ‘Rosie the Riveter’.

Women Line Up for Paychecks, Richmond Shipyards, c. 1944 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Women Line Up for Paychecks, Richmond Shipyards, c. 1944 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

1954

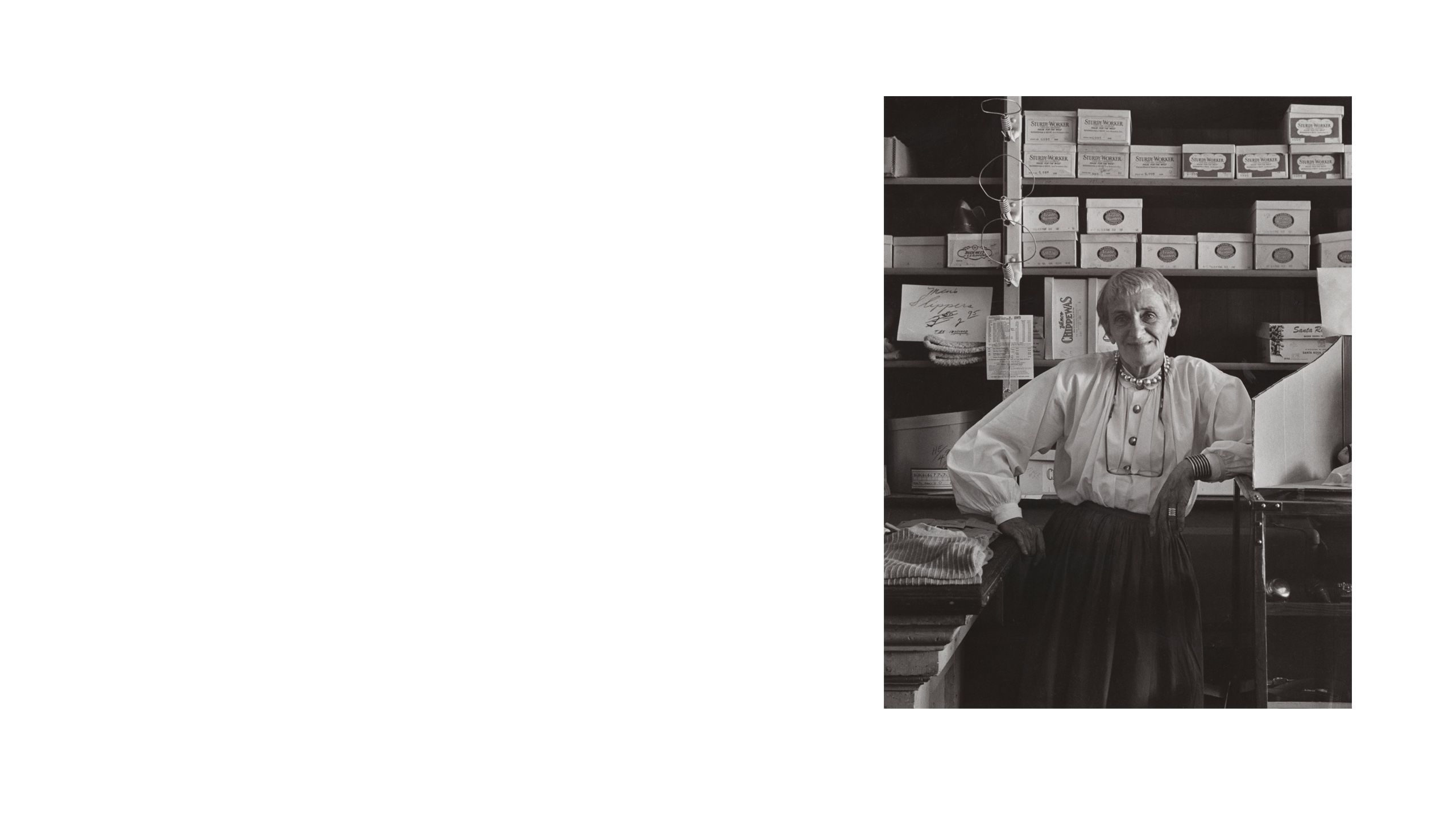

Inspired by a book titled The Irish Countryman (1937) by Conrad M. Arensberg, Lange persuaded the editors of LIFE to commission her and her son Daniel Dixon, a writer, to create an in-depth study of rural life in Ireland. The

trip was her first overseas, and Lange spent six weeks in the autumn of 1954 photographing the experience of life around County Clare in western Ireland.

Travelling around the countryside from Tubber to Ennis, Lange captured country markets and fairs, pubs, local shops, and church-goers attending mass on the ‘island of the devout’, as LIFE later dubbed the country.

1955

In the mid-1950s, Dorothea Lange started work on a photo-essay exploring a new public defender scheme in the US legal defence system that offered judicial representation to people unable to afford a lawyer. For months, Lange followed Martin

Pulich, a 36-year-old chief assistant public defender at the Alameda County Courthouse in downtown Oakland, who handled hundreds of public defence cases every year.

Made against the backdrop of a growing civil rights movement, Lange sought to expose prejudice and inequality in the American justice system, which particularly affected those of modest means and black or Asian minorities.

Judge Fox, Oakland, California, 1957 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

Judge Fox, Oakland, California, 1957 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

1956-57

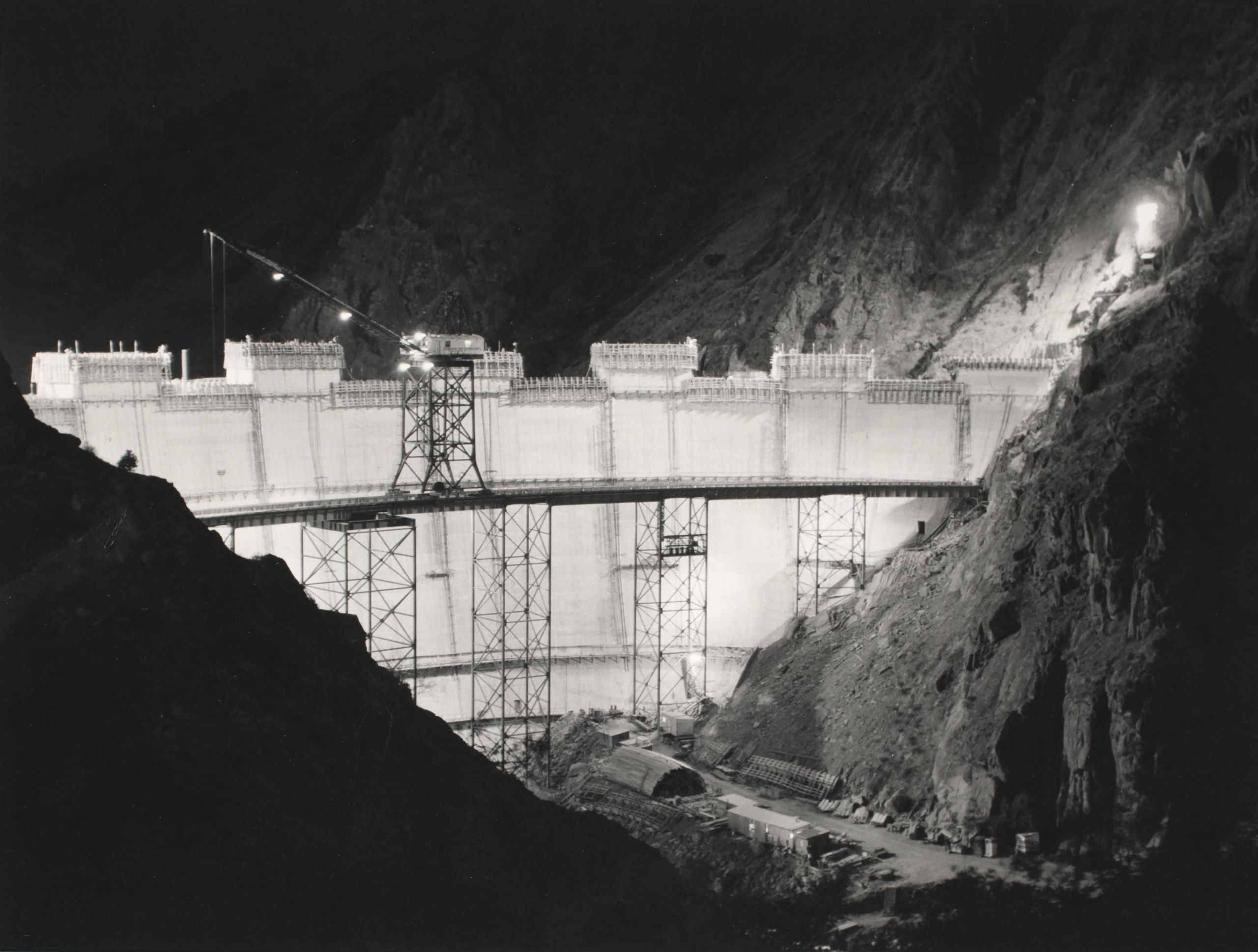

In the early 1950s, the US Bureau of Reclamation initiated a large-scale project to construct a new dam in Putah Creek, 85 kilometers north of San Francisco, to provide the growing population of the Bay Area with much needed water. As

part of its construction, the small rural town of Monticello nestled in the Berryessa Valley was earmarked for demolition.

Joining forces with the photographer Pirkle Jones (1914-2009), Lange chronicled the vanishing town and valley between February 1956 and February 1957 in a photo-essay that served as a rallying cry for environmental campaigners.

1964-65

Lange was the first female photographer to be offered a retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1964. Already seriously ill with oesophagus cancer when working with Curator John Szarkowski to prepare the exhibition,

Lange died in October 1965 at the age of seventy, several months before the retrospective opened to critical acclaim on 25 January 1965.

‘I would like to add a line to encourage persons interested in using a camera to concern themselves with making photographs of the life which surrounds them, to raise his [or her] sights to include what’s going on about us, to use the cameras to show this awareness.’

Dorothea Lange, concluding statement of MoMA retrospective

About Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing

The first UK retrospective of American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965). Lange was a powerful woman of unparalleled vigour and resilience. Using her camera as a political tool to shine a light on cruel injustices, Lange went on to become a founding figure of documentary photography.

Part of a photography double bill with award-winning contemporary photographer, Vanessa Winship: And Time Folds.

Part of The Art of Change, our 2018 annual theme which explores how the arts respond to, reflect and potentially effect change in the social and political landscape.

Photo: A Sign of the Times, San Francisco , 1934 © The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California