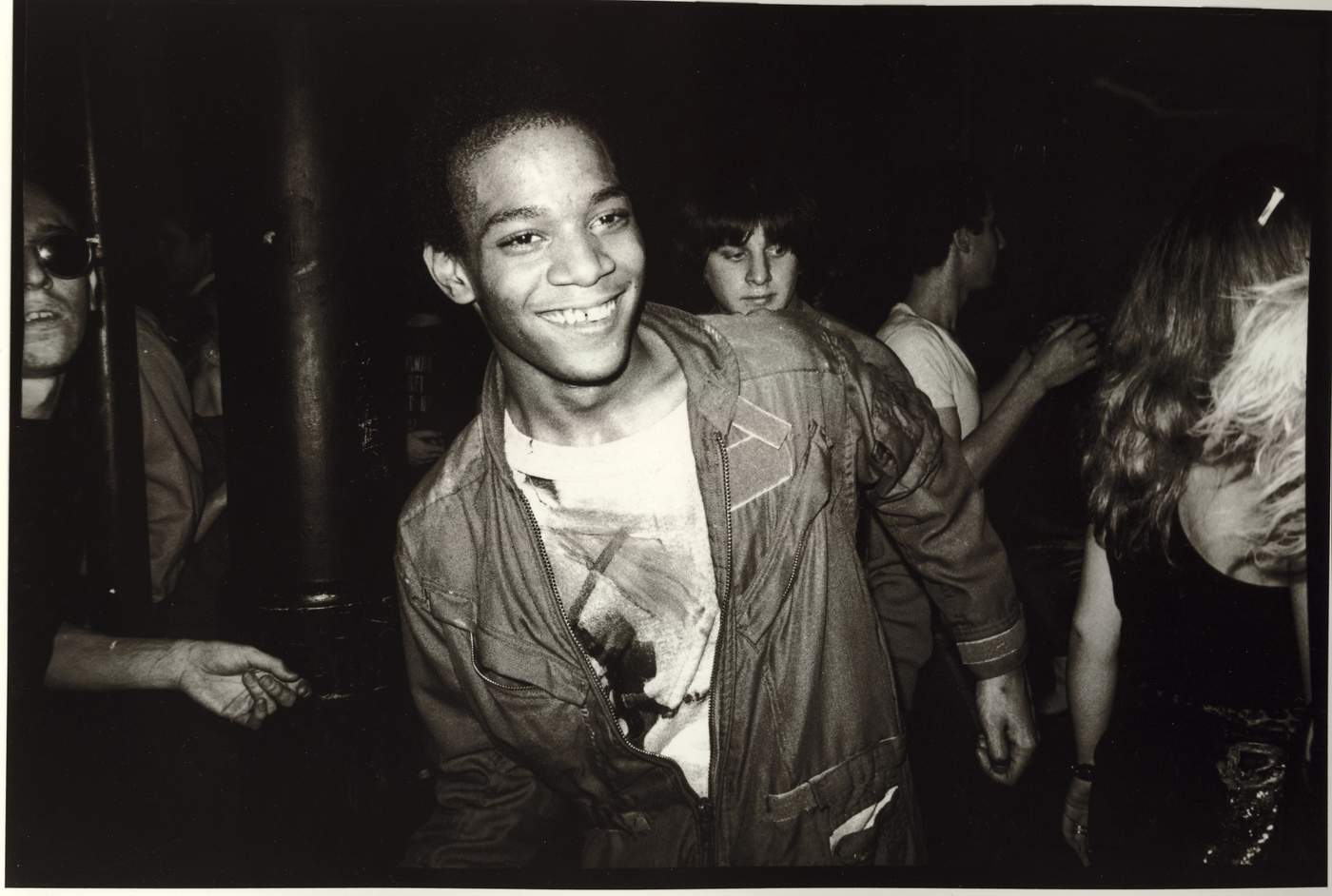

Photo: Jean-Michel Basquiat dancing at the Mudd Club, 1979© Nicholas Taylor

During the late 1970s and early 1980s a cultural renaissance of arguably unprecedented proportions reached its climax in downtown New York. Determined to pursue lives that were more creative, flexible and open than those led by their hedged in, nine-to-five, socially conservative parents, a generation of young artists drove the phenomenon.

The warehouses of SoHo, TriBeCa and NoHo, the entertainment hangouts located on the Bowery and the run-down tenements of the Lower East Side - newly affordable and available thanks to the city’s embattled shift to a postindustrial economy - provided them with places to work, socialise and, every now and again, sleep.

‘Downtown was like this kaleidoscopic, smörgåsbord of activity,’ recalls performance artist and Club 57 manager Ann Magnuson of the creative crescendo, ‘All of these ideas were out there. It was like Halloween every night.’

Basquiat’s turntable forays spoke to a wider downtown culture of anti-specialist adventure that he in some respects embodied. Along with downtown impresario Michael Holman, he formed Gray - named after Gray’s Anatomy, Basquiat’s favourite reference book - as an alternative line-up that featured unskilled musicians who approached their instruments as if they were aliens in search of beautiful sounds.

Around the same time the Brooklyn artist became a regular contributor to TV Party, a DIY punk cable TV show co-founded by downtown scenester Glenn O’Brien. O’Brien subsequently wrote New York Beat, later released as Downtown 81. Featuring Basquiat playing the lead, the film revolved around a semi-fictional day in the life of a struggling, homeless downtown artist.

'Basquiat’s forays into the party scene and alternative art forms shaped his artistic style...'

Then, in 1983, Basquiat produced the surreal, experimental rap track ‘Beat Bop’ by Rammellzee vs. K- Rob. The only constraint, it seemed, was time.

Basquiat’s forays into the party scene and alternative art forms shaped his artistic style, which came to be infused with the declarative gestures of graffiti, the wittily acerbic intellectualism of the art-punk crowd, the improvised bravado of TV Party, the striking juxtapositions developed by downtown DJs, and the discordant strains of no wave outfits such as DNA.

Basquiat’s closest friends included O’Brien, Cortez, Haring, graffiti artist Futura, Arto Lindsay, John Lurie of the Lounge Lizards, and downtown movie star Patti Astor. Astor went to open the Fun Gallery with partner Bill Stelling as the first East Village art gallery and invited Basquiat to stage a solo show in November 1982.

‘I made the best paintings ever,’ the artist recounted later of the work he created for the show. Cortez agreed and concluded that the ‘funkiness’ of Astor and Stelling’s setting, which operated as a downtown clubhouse/party space, inspired his efforts.

LIKE AN IGNORANT EASTER SUIT, Jean-Michel Basquiat on the set of Downtown 81, Edo Bertoglio ©New York Beat Film LLC

For the most part, the cultural renaissance of late 1970s and early 1980s NYC ended up being overlooked or dismissed. The hybrid character of much of the activity enabled it to connect powerfully with its immediate audience yet hindered its chances of achieving a national and international reach. The scene’s performative, improvisatory and ephemeral underpinnings made its output resistant to fixing, cataloging and archiving. The interdisciplinary and democratic mindset of participants confounded critics, gallerists and art institutions. Meanwhile the fact that so much of the activity unfolded in subterranean party spaces rather than established galleries, concert halls and art institutions, with upstart club owners and promoters playing improbably groundbreaking curatorial roles, made it difficult for critics and historians to register.

During the early 80s, with its queer and black contingents on the defensive, the creative community was forced to come to terms with rapidly rising rents, escalating inequality and NIMBY gentrification. Mayor Giuliani’s ‘Zero Tolerance’ strategy closed many of the spaces in which subsequent activity might have taken root. Mayor Bloomberg did nothing to stop the city entrenching its position as the world capital for the rich - a city in which an itinerant, penniless successor to Basquiat could never make a stand.

Yet scenes never die out completely; instead they shift ground in response to changing economic and cultural circumstances. Brooklyn went on to host the most prolific counter-scene of recent decades, with concentric scenes developing in affordable parts of the city and beyond.

Meanwhile the rising profile of Basquiat opens up an opportunity to explore not only his art but also the scene and wider milieu that shaped it.

Listen to the sounds of Downtown NYC in our Spotify playlist.

About Tim Lawrence

Tim Lawrence, professor of Cultural Studies at the University of East London, is the author of Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-83

About Basquiat: Boom for Real

Basquiat: Boom for Real is the first large-scale exhibition in the UK of the work of American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960—1988). Drawing from international museums and private collections, Basquiat: Boom for Real brings together an outstanding selection of more than 100 works, many never before seen in the UK.

The exhibition took place in the Barbican Art Gallery from 21 Sep 2017-28 Jan 2018